The research

A state of affairs

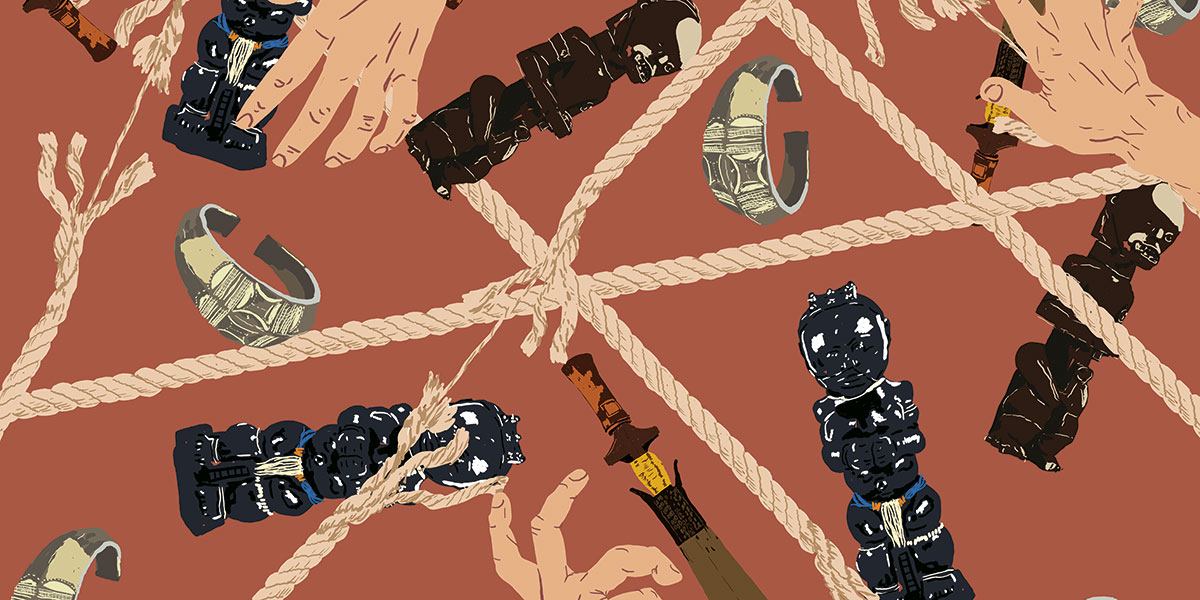

Contemporary museums are faced with the challenge of confronting their colonial past. The (Tr)african(t)s project, which studies collections from former territories colonized by Spain, aims to trace the origin of these pieces and rethink their meaning in a postcolonial context. It also seeks to promote a critical dialogue on historical reparation, with the active participation of diasporas and institutions from the affected territories.

Share

Contemporary museums in colonial situations. A state of affairs

The damage done by European empires over five hundred years of history cannot be undone. The processes of wealth accumulation that flowed in the direction of the European metropolises have shaped a profoundly unequal world.

In one way or another, the multiple conflicts between the North and the Global South are the result of this structural imbalance. In parallel to economic domination, the European empires imposed upon the dominated populations their models of governance, their laws—in short, their narratives—which were often accompanied by brutal practices of control. Redressing part of the accumulated grievances seems an immense task, only within the reach of major agreements within the international community. Reparation processes thus call for the transformation of global legislative frameworks and, sooner or later, political recognition of a change in relations between former metropolises and ex-colonies.

It is perhaps daring to think that the accumulation of small initiatives against such a solid hegemony will be of any use, but this is the ultimate goal of projects such as (Tr)african(t)s. Museums and Collections of Catalonia in the Face of Coloniality. In this sense, the project assumes, on the one hand, that numerous pieces and specimens from the former colonies of the late Spanish Empire (the Philippines, Morocco, and Equatorial Guinea) were acquired under conditions imposed by the dominant power. Sometimes these conditions were explicit, such as plundering them as spoils of war, prohibiting their use in the context of rituals that the colonial administration wanted to extinguish, or determining the selling prices; on other occasions, colonial intervention was felt by simply imposing a general impoverishment of the populations that pushed them to get rid of their possessions.

The project assumes, on the one hand, that numerous pieces and specimens from the former colonies of the late Spanish Empire (the Philippines, Morocco, and Equatorial Guinea) were acquired under conditions imposed by the dominant power

On the other hand, the awareness of having suffered a plundering of their natural and cultural heritage is growing and spreading among the communities formerly subjected to the declining empire. There is no reason to believe that this process will stop. The European museums that house these now uncomfortable and often poorly studied collections, stake much of their legitimacy on the sensitivity and conviction with which they respond to the demands they receive, and will continue to receive, from the former colonies or from the people living in our country.

The collections of colonial origin of the Catalan museums that form part of the (Tr)african(t)s network are thus subjected to provenance research. This involves analytical methodologies that seek to reconstruct as accurately as possible the conditions under which they entered the museums where they are currently located, as well as the acquisition procedures carried out by their collectors. The objective is to evaluate the influence exerted by the colonial situation on the configuration of the museum collections of the former metropolises. In this sense, the project aligns with the set of policies of reparation for colonial domination initiated in recent years in Europe, policies in which the former ethnological and natural history museums seem to be playing a central role.

The awareness of having suffered a plundering of their natural and cultural heritage is growing and spreading among the communities formerly subjected to the declining empire. There is no reason to believe that this process will stop

By gathering the most precise information possible on the conditions of acquisition of these collections, we want to establish their traceability and offer the results of the research to three different types of actor: firstly, to the museums themselves, in the hope that with the information provided they will want to modify the narrative surrounding these collections and intervene in their museography; secondly, to the entities representing the diasporas coming from the former colonies, who often do not have complete information on the aforementioned collections or are even unaware of their existence; and thirdly, to the bodies and entities in the former colonies that are concerned with heritage protection and which—often like the entities in the diaspora—are unaware of the existence and circumstances surrounding these collections. At the same time, the project plans to launch a series of activities to raise awareness about these collections and the conflicts arising from them, such as exhibitions, documentaries, digital tools, publications or public programmes.

The decision-making process in the research and subsequent formalizations involves the active participation of entities and individuals who represent or are part of the diasporas from the former colonies. This is a sine qua non condition for the success of the project.