Summary of results

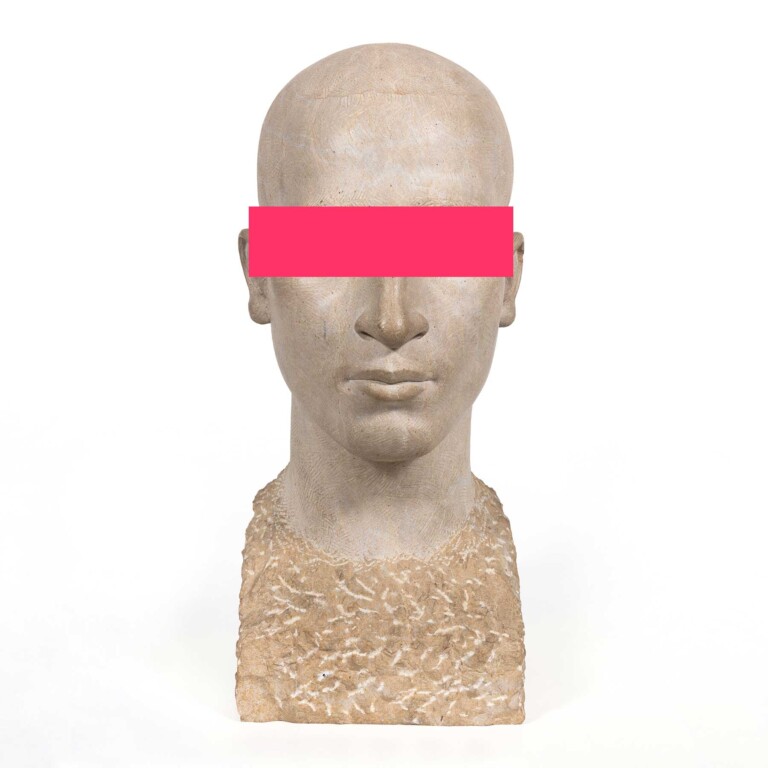

This is one of the ‘anthropological sculptures’ made by the sculptor Eudald Serra during the third expedition organized by the MEB to the northern part of the Spanish Protectorate in Morocco, in this case between 27 December 1955 and 25 January 1956. The piece, modelled in bronze, is accompanied by preliminary sketches in clay.

In all probability, the model used to sculpt the head was Lahadar ben Caddur ben Milud [sic], son of Caddur and Hadduna, a member of the Ulad Seguer [sic] berber tribe. In the testimony given by the model to August Panyella or to Eudald Serra himself, he claimed to be a member of this berber tribe, from the village of ‘Haguara’, two kilometres from Uxda and therefore outside the territory under Spanish administration. According the same notes, Panyella referred to the model as a ‘nationalist prisoner’ (MEB_L128_07_02).

Consequently, the information provided by the model to his interlocutors must be taken with great caution. In the area of Uxda, in fact, we did not find any berber tribe with a name similar to ‘Ulad Seguer’, nor any village or aduar close to Uxda with a name similar to ‘Haguara’. Even the name itself given to the Spanish guard or police must be questioned. It is logical to think that the individual, a prisoner of the Spanish forces in Chefchaouen for having participated in some anti-colonial and/or pro-independence activity, would want to protect his identity, as well as that of his family, for fear of reprisals. Panyella’s diary adds: ‘In Xauen [sic] prison. He worked in Uxdá, and has large scars from a tractor’ (MEB_L128_07_02).

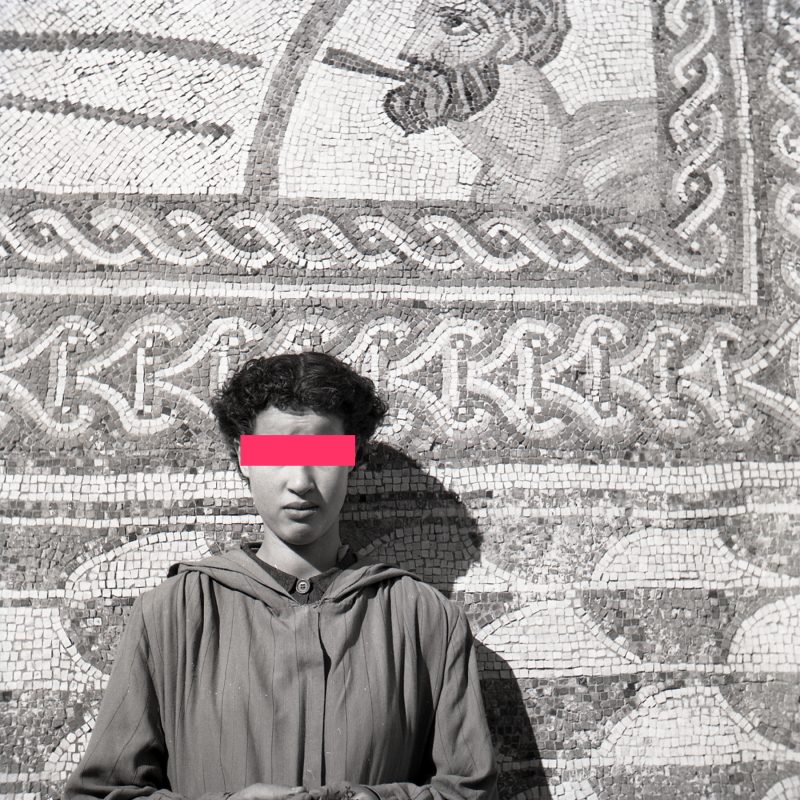

However, we can identify the person thanks to a comparison between the information provided in August Panyella’s diary and the photographs taken during the 1956 expedition. In one of them, with inventory no. 2768, we can clearly see Eudald Serra modelling the clay head of the individual identifiable in piece 46-2. The man, dressed in worn clothes, seems to be guarded by two mehzanis from the Spanish Army, and the presence of maps allows us to identify the room as the office of the cartographer of the Office of Intervention in Chefchaouen. His status as a prisoner would be consistent with the fact that he was being guarded while being used as a model. Three other photographs from the same expedition—numbered 2629, 2630 and 2631 in the photographic inventory—also allow us to identify the same individual from the face, profile and upside down. In fact, the profile photo (2630) shows mountains in the background that could correspond to the mountainous terrain of Chefchaouen. The inventory of the photographic collection leaves little doubt about this, as it confirms that the photographs were taken in Chefchaouen.

August Panyella’s diary enables us to pinpoint the day on which Serra made the clay sketch of Lahadar ben Kaddur ben Milud: 7 January 1956. In the same diary (MEB_L128_07_02), the payment made to the model is indicated: 50 pesetas, plus an additional 2.50 pesetas in tobacco. In the ‘official’ list of expenses that Panyella signed on 31 December 1955—most likely drawn up at a later date, but assigned to the calendar year 1955—the fees for two sessions attributed to the ‘Ulad Seguer model’ amounted to 75 pesetas (MEB_L128_07_02).

Regarding the final acquisition of the bronze copy, the catalogue Escultures antropològiques d’Eudald Serra i Güell (Anthropological Sculptures by Eudald Serra i Güell), published by the Barcelona City Council and the Folch Foundation (1991: 32), states that it took place in 1965. However, the record corresponding to file 46, to which the piece belongs, indicates that the final payment of nine thousand pesetas to Serra was made on 28/12/1970.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The first draft was drawn up in Morocco itself, on 7 January 1956, and then sent to Tétouan. There, Mr. Alejandro Tomillo, who worked for the Moroccan Excavations Inspectorate and was therefore closely linked to the staff of the Archaeological Museum, was commissioned to empty and prepare the clay heads for shipment to the port of Barcelona, according to the invoice issued by Mr. Tomillo to the MEB dated 24 January 1956, the day before the departure of the expedition, for which he was paid five hundred pesetas.

The sketch was sent in box number 5. We do not know precisely when the freight arrived in Barcelona, nor do we know when the sculptor Serra transformed the sketch into its definitive bronze copy, but it must have happened during the months immediately after the return of the expedition to Barcelona, because Mr. Serra sent an invoice to the MEB, dated 12 April 1956, requesting fees for the production of six bronze sculptures on behalf of the museum. The total fee amounted to twenty-four thousand pesetas, which means that the sculptor was paid four thousand pesetas for each of the heads.

Estimation of provenance

Chefchaouen, Morocco, 1956

Possible alternative classifications

No possible alternative classifications are perceived.

Complementary sources

Archives:

Arxiu del Museu Etnològic de Barcelona

Arxiu Panyella-Amil, caixa A7 expedient 5

L128 05 02

L128 05 04

L128 06 07

L128 07 01

L128 07 02

L128 07 06

Fundació Folch de Barcelona

Eudald Serra. Cuadernos de viaje, 1947-1991

Bibliography:

Etxenagusia Atutxa, B. (2018). La prostitución en el Protectorado español en Marruecos (1912-1956) (tesi doctoral). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Goffman, E. (2007). Internados. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Gonzalbes, E., i Parodi, M. J. (2011). Miguel Tarradell y la arqueología del Norte de Marruecos. Dins D. A., Arqueología y turismo en el Círculo del estrecho (p. 199-220). Cadis: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz.

Huera, C., i Soriano, D. (1991). Escultures antropològiques d’Eudald Serra i Güell. Barcelona: Fundació Folch i Ajuntament de Barcelona.

López Bargados, A., i Martín López, S. (2022). Entre zocos e internados. Itinerarios y procedimientos en las expediciones del Museo Etnológico y Colonial de Barcelona al Protectorado español sobre Marruecos (1952-1956). Ajuntament de Barcelona.

Madariaga, R. M. (2019). Marruecos, ese gran desconocido. Madrid: Alianza.

Marín, M. (2015). Testigos coloniales: españoles en Marruecos. Barcelona: Bellaterra.

Mateo Dieste, J. L. (2002). La paraetnografía militar colonial: poder y sistemas de clasificación social. Dins A. Ramírez i Bernabé López García (ed.), Antropología y antropólogos en Marruecos (p. 113-133). Barcelona: Bellaterra.

—(2003). La «hermandad» hispano-marroquí. Política y religión bajo el Protectorado español en Marruecos (1912-1956). Barcelona: Fundació la Caixa.

Mathieu, J., i Maury, P. H. (2013). Bousbir, la prostitution dans le Maroc colonial: ethnographie d’un quartier reserve. París: París-Méditerranée.

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

—(2016). Crítica de la razón negra. Ensayo sobre el racismo contemporáneo. Barcelona: Futuro Anterior.

Rahola, F. (2007). La forme-camp. Pour une généalogie des lieux de transit et d’internement du présent. Cultures & Conflicts, 68, 31-50.

Rigoulot, P., i Kotek, J. (2000). Le siècle des camps. Détention, concentration, extermination, cent ans de mal radical. París: J.-C. Lattès.

Rivet, D. (2012). Histoire du Maroc. De Moulay Idris à Mohamed VI. París: Fayard.

Sánchez Gómez, L. A. (1992). La antropología al servicio del Estado: El instituto «Bernardino de Sahagún» del CSIC. Disparidades, 47(1), 29-44.

Smith, I. R., i Stucki, A. (2011). The colonial development of concentration camps (1868-1902). Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 39(3), 417-437.

Soriano, M. D. (2010). Historia, tradición y cultura: Las colecciones africanas del período colonial del Museu Etnològic de Barcelona. Dins Actes del 7è Congrés Ibèric de Estudis Africans (p. 1-20). Lisboa.

Stoler, A. L., i Cooper, F. (1997). Between metropole and colony: Rethinking a research agenda. Dins F. Cooper i A. L. Stoler (ed.), Tensions of empire: Colonial cultures in a bourgeois world (p. 1-56). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stucki, A. (2018). «Frequent deaths»: The colonial development of concentration camps reconsidered, 1868-1974. Journal of Genocide Research, 20(3), 305-326. <https://doi.org/10.1080/14623528.2018.1429808>.

Taraud, C. (2003). La prostitution coloniale. Algérie, Maroc, Tunisie (1830-1962). París: Payot.

![2768v2 Sr. Serra modelant cap berber al taller del fotògraf [sic]; Xauen](https://trafricants.org/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/2768v2-1-r1s3naz0e9jpfdk332eci3myow1y18s3l4ttuptphc.jpg)