Summary of results

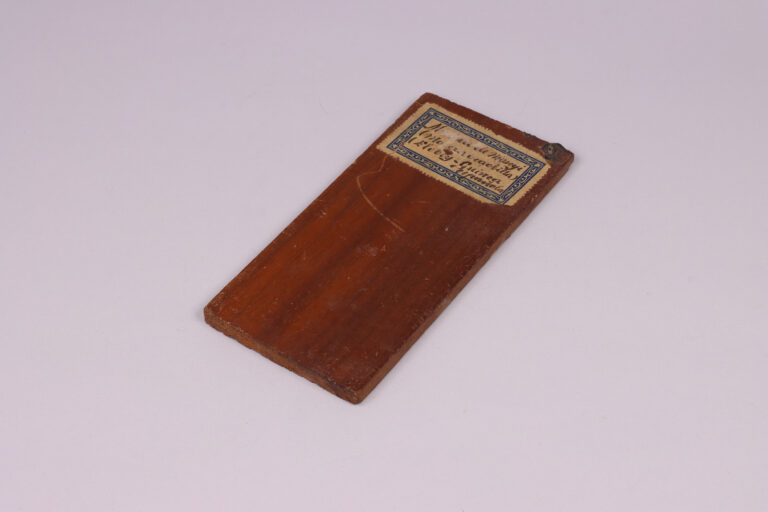

This piece of wood, part of a collection of samples made by the Claretian missionaries, highlights the relationship between evangelization, exploitation, and colonialism.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The museum’s file lists three obviously incompatible dates: 1926, 1950, and the second quarter of the 20th century. It is possible that the pieces date from slightly earlier. They are labelled ‘Elobey’, probably not referring to the homonymous islet (Elobey Chico), where there were few trees, but to the sub-government of Elobey, which grouped together all the territories located south of the Wolo River in Spanish Guinea (the northern part was under the subgovernment of Bata). In 1926, the capital of the Elobey subgovernment was moved to the mainland, to Kogo. And in 1930, the district of Elobey disappeared as such and the capital of the entire mainland (the territory known as ‘Muni River’) was transferred to Bata. Therefore, these samples cannot date from after 1930.

These samples were probably prepared at the beginning of Governor Núñez de Prado’s term of office (1925–931), when the ‘indigenous logging’—carried out by the people of the area, who threw the logs into the river to take them to the commercial factories on the coast—was coming to an end on the mainland of Guinea. It was the time when the exploitation of the forests by European forestry companies was taking place, through new laws that deprived the Guineans of access to their ancestral lands with administrative measures that granted concessions to European businessmen—many of them very well linked to the governor Núñez de Prado or to his mistress, María Bau. The Claretians were involved in the promotion of the colonial economy. Undoubtedly, this collection of wood samples was destined at that time to show the Spanish businessmen the possibilities of the equatorial colony that was then beginning to be fully exploited. In this period, the continental territory had just been conquered and the basic infrastructures of the colony were being built by means of forced labour.

At the 1929 Barcelona Missionary Exhibition, the Claretians already showed a set of woods from Guinea, which could be this one (object 2212 in the catalogue). It is possible that this piece left Guinea to be displayed at that exhibition and never returned.

Estimation of provenance

–

Possible alternative classifications

–

Complementary sources

Bibliography:

Botargues Martija, M. C. (2010). Colecciones Etnográficas e Historia: El Museo Claretiano de Malabo. Dins 7.º Congreso de Estudios Africanos en el Mundo Ibérico, CIEA7, 1, Lisboa.

Exposición de Barcelona (1929). Exposición Misional: Catálogo ilustrado de los objetos expuestos en el Palacio de las Misiones. Barcelona: Llibreria Camí.

Guerra Velasco, J. C. i Pascual Ruiz-Valdepeñas, H. (2015). Dominando la colonia: Cartografía forestal, negocio de la madera y apropiación del espacio en la antigua Guinea Continental Española. Scripta Nova. Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, (19).

—(2017). La selva como argumento: Imaginario geográfico, discurso forestal y espacio colonial en Guinea Ecuatorial (1901-1968). Cuadernos Geográficos, 56(1), 6-25.

Nerín, G. (2015). Corisco y el estuario del Muni: Del aislamiento a la globalización y de la globalización a la marginación. París: L’Harmattan.