Summary of results

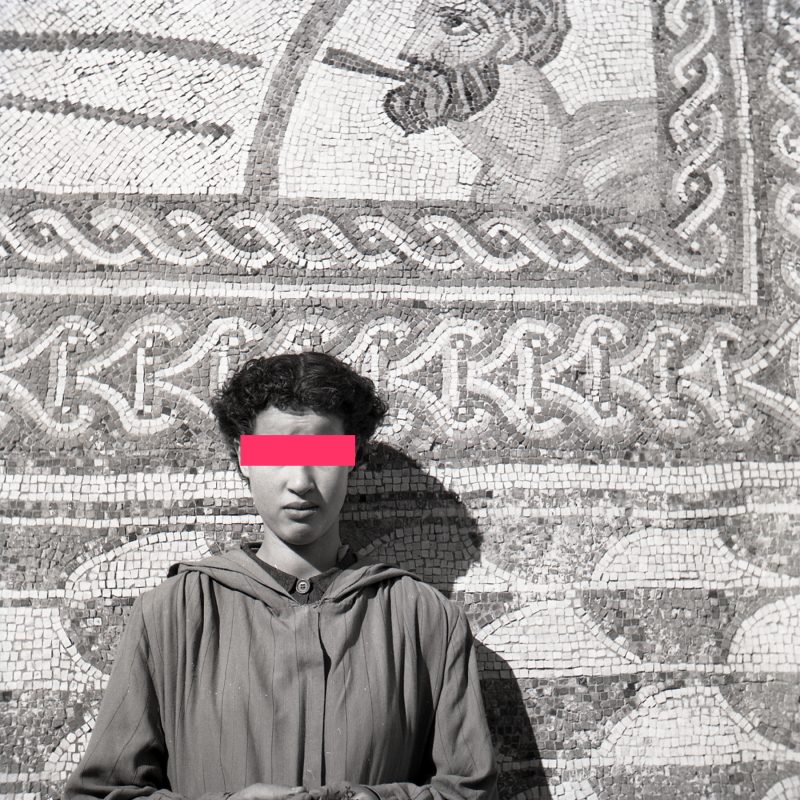

This is a photograph taken, quite plausibly by Eudald Serra, in the prison of Nador, in the Eastern Rif, probably on 24 April 1954, as part of the second MEC expedition to the northern part of the Spanish Protectorate in Morocco. Three inmates, probably punished for having become pregnant out of wedlock, were sentenced to between two and three years, with their corresponding children. The expeditionaries made systematic use of this type of ‘total institutions’ in their search for models for Serra’s ‘anthropological sculptures’.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

It is a photograph of three female inmates in Nador prison. Eudald Serra, in his diaries, is very explicit when he points out that, after visiting the prison on 23 April and having made a bust of one of the inmates, he returned the following day to finish the work. He continues:

‘I go to nine o’clock mass and then I go to the prison to continue with the head. First I try to take some photographs in the prison yard. At the moment, only a few of them want to be photographed. Afterwards, they all put on the best clothes they have and ask me to take their pictures’ (Serra, Travel Journals, 1947–1991).

Thus, this photograph is part of a series (no. 23997-24002) taken in the courtyard of Nador prison where, according to Serra, the women wore their best clothes with the intention of being photographed.

This is Serra’s account of his experience in Nador prison: an initial distrust on the part of the inmates which, on seeing the artistic and scientific intentions surrounding the presence of the MEC expeditionaries, turned into curiosity and even a certain eagerness to collaborate. The idea, however, that it was the inmates themselves who decided of their own accord to have sumptuous photographs taken is highly implausible. It seems more likely that, in an attempt to offer a friendly face to the institution, it was the prison administration which opted to take the step and ‘urged’ the inmates to stand in the courtyard in front of Serra’s camera. Certainly, we have no information to confirm this, but the attitude of the inmates in front of the camera, the gesture of defiance and even a certain hostility that is captured in some cases, as in the case of the cliché in question, is reminiscent of the series of photographs that Marc Garanger (1935–2020) took of Algerian women during the war of liberation (1960–1962). In these, we can perceive the subjection of the person portrayed to a non-consensual photographic activity for identity control purposes and, at the same time, the various forms of resistance manifested through a belligerent gesture: women who lower their eyes and heads to avoid being reliably portrayed, who look defiantly at the camera, who refuse to smile or who adopt a grimace of displeasure, and so on. In the case of the cliché in question, no. 23999, the three women portrayed seem to adopt some of these tactics of resistance in front of the camera, and in this sense seem to contradict Serra’s fiction of consent.

We also need to remember the severity of the punishment the inmates were suffering. Speaking of the woman he had chosen the day before to prepare a bust, Serra mentioned:

‘She is from a nearby berber tribe and is there for illegitimate pregnancy, like most of them, except for one called the corporal, who is there for being an accomplice in a crime that happened twelve years ago. The penalty for illegitimate pregnancy ranges from two to three years for unmarried women and from five to seven for widows and six for divorced women’ (Serra, Travel Journals, 1947–1991).

The harshness of a similar internment does not make very credible a cooperative attitude on the part of the inmates, and at the same time makes clear the connivance between the supposedly scientific and artistic practices carried out by the MEC expeditionaries and the colony’s confinement institutions.

Beyond the aforementioned, we do not have any relevant information that could provide us with aspects of the biography or identity of the people portrayed. It would be necessary to search in the General Archive of the Administration in Alcalá de Henares to find the judicial files and/or entry forms of the inmates. We are not aware that the photograph in question has been used in any of the exhibitions that the MEC/MEB/MuEC has devoted to Morocco over the years. If the provenance research is correct, the photograph would have been added to the MEC collection in May 1954, like the rest of the photographs in the collection.

Context d’adquisició

«La joya de la corona de las actividades científicas a las que contribuían las campañas de Marruecos eran las “esculturas antropológicas” que modelaba Eudald Serra, compañero infatigable de Panyella, entre otras, en las expediciones al protectorado. Serra, un personaje cosmopolita con una larga experiencia personal en Japón (Huera i Soriano, 1991: 10) y otros países asiáticos, aportaba a la expedición —al margen de otros intangibles— la excelencia de su técnica escultórica, capaz de llevar a cabo representaciones extremadamente fieles de la fisonomía humana. En un contexto en el que la captación fidedigna de los rasgos fenotípicos se consideraba de enorme utilidad para la determinación de las identidades raciales y para la configuración de una retórica frenológica, los bustos elaborados por Serra añadían un incuestionable interés artístico que hacía de ellos piezas destacadas de cualquier expedición. […]

Estimation of provenance

Nador (in tarifit ⵏⴰⴹⵓⵕ; in Arabic الناظو), Eastern Rif, Morocco

Possible alternative classifications

As for the museographic information on the piece, the existence of the women’s prison in Nador as a place of confinement to which Eudald Serra systematically resorted in search of models for the ‘anthropological sculptures’ he made on behalf of the museum should be made clearer.

Complementary sources

Archives:

Arxiu del Museu Etnològic de Barcelona

Arxiu Panyella-Amil, caixa A7, expedient 5

MEB, L128 05 02

MEB, L128 06 07

MEB, L128 07 01

MEB L128 07 02

MEB, L128 07 06

Fundació Folch de Barcelona

Eudald Serra. Cuadernos de Viaje, 1947-1991

Bibliography:

Etxenagusia Atutxa, B. (2018). La prostitución en el Protectorado español en Marruecos (1912-1956) (tesi doctoral). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Huera, C., i Soriano, D. (1991). Escultures antropològiques d’Eudald Serra i Güell. Barcelona: Fundació Folch i Ajuntament de Barcelona.

Mathieu, J., i Maury, P. H. (2013). Bousbir, la prostitution dans le Maroc colonial: ethnographie d’un quartier reserve. París: París-Méditerranée.

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Taraud, C. (2003). La prostitution coloniale. Algérie, Maroc, Tunisie (1830-1962). París: Payot.

Valderrama, F. (1956). Historia de la acción cultural de España en Marruecos, 1912-1956. Tetuan: Marroquí.

![2768v2 Sr. Serra modelant cap berber al taller del fotògraf [sic]; Xauen](https://trafricants.org/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/2768v2-1-r1s3naz0e9jpfdk332eci3myow1y18s3l4ttuptphc.jpg)