Síntesi dels resultats

The bejuco women’s saddle from the province of Camarines Sur, Philippines, is an object that reflects the complex cultural and political interaction of the Spanish colonial period. Donated by Regino García y Baza, a renowned Filipino artist and botanist, the piece was part of the Philippines Exhibition, organized by Víctor Balaguer in Madrid in 1887. Later, in December of that year, García himself donated it (along with another mount) to the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum.

The saddle was displayed in the ‘Population’ section of the exhibition, which was intended to show everyday Filipino life to European visitors from an ethnographic perspective. After the exhibition, the saddle was donated to the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, becoming part of a collection illustrating cultural exchange and colonial rule at the time. It was sent to Spain through a centralized system of artefact collection, reflecting colonial hierarchies that involved local elites under the supervision of colonial authority. While García’s donation was part of an effort to preserve Filipino cultural wealth, it must also be understood within the framework of prevailing power dynamics and colonial narratives.

Víctor Balaguer, a prominent Catalan politician and intellectual, played a key role in the organization of the Madrid exhibition. As Minister of Overseas and founder of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, he was one of the main driving forces behind the collection and exhibition of colonial artefacts. Balaguer’s correspondence and the Butlletí de la BMVB mention the sending of objects to Vilanova after the exhibition. Donations from the exhibition were recorded between October 1887 and February 1888, although some objects did not appear in the museum’s publications. Balaguer facilitated the transfer of these objects to Vilanova, thereby consolidating his role as a key promoter of cultural dissemination and the Filipino legacy in Europe.

The exhibition included a wide range of artefacts intended to provide an understandable insight into Filipino life and culture. However, the descriptions and contextualization of these objects were often insufficient, limiting the public’s understanding of the true cultural and religious complexity of the Philippines.

The Philippines Exhibition of 1887 had a significant impact on public perception and Spanish colonial policy. It was an attempt to reassert colonial control and demonstrate Spanish knowledge and dominance over the Philippines. The inclusion of a human zoo, where people from the regions most resistant to Spanish rule were exhibited, reflected the need to justify colonial presence and actions. The arrival of the piece in Vilanova and its subsequent exhibition symbolize the legacy and contradictions of Spanish colonialism, as well as the interest in documenting and preserving cultures that were altered and reinterpreted through a colonial lens.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

- Regino García y Baza, artista, botànic i forestal filipí.

The first news we find of this piece appears in the Butlletí de la Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer of December 1887. This entry states that Regino García y Baza made a donation of two Albayan saddles or saddles and two knives (bolos). At the same time, the Catalogue of the Philippines Exhibition also records that Regino García y Baza donated two bejuco saddles, one for women and the other for men, both from the province of Camarines Sur (formerly known as ‘Nueva Cáceres’). Thanks to this information, we can deduce that the female saddle mentioned in the bulletin and in the catalogue is the one mentioned in this provenance report.

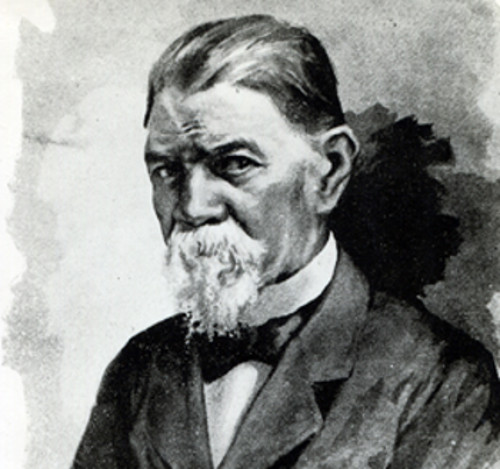

Regino García y Baza (1840–1916) was a prominent Filipino artist, botanist, and forester. García trained as a surveyor, painter and botanist, and was actively involved in civil service, which allowed him to apply both his artistic and scientific skills to multiple projects. He was chief of staff at the Manila Botanical Garden and a member of the Spanish Society of Natural History. One of his most outstanding works is The Labrador, a painting on display at the Prado Museum.

Regino García y Baza was selected by Sebastián Vidal y Soler, who directed the Philippine participation in the exhibition, to assist in both the preparation and display of the elements representing the Philippines. García supervised the construction of the bamboo and nipa houses that recreated the typical structures of the archipelago and directed the exhibits in the forest section. His ability to classify and display botanical specimens was essential in providing a sample of the island’s forest wealth.

García’s contribution was widely recognized during the exhibition. He received honourable mentions for his paintings depicting Filipino views and subjects, as well as a gold medal for the rice exhibits at the Philippines Exhibition in Madrid in 1887 and at the 1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition. His work was instrumental in highlighting the diversity and abundance of natural resources in the archipelago, although these exhibitions were framed within a narrative that served colonial interests.

We know that objects from the Philippines Exhibition were sent to the BMVB thanks to Víctor Balaguer. Víctor Balaguer i Cirera (1824–1901) was a Catalan politician, writer, journalist, and historian. In 1884, he opened the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum in Vilanova i la Geltrú, which became an institution that offered library, newspaper library, museum, and teaching centre services. He served a third term as Minister of Overseas (from 10 October 1886 to 14 June 1888), promoting important reforms in tariff policy, public works and transport, and communications. Balaguer also promoted the creation of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, in Madrid—which he directed until his death—and the Museo Biblioteca de Filipinas, in Manila. At the same time, Balaguer was the true architect of the organization of the Philippines Exhibition, held from 30 June to 30 October 1887, in the Retiro Park in Madrid.

In the Butlletí de la BMVB of July 1887, page 5, the big news is the inauguration of the exhibition by Víctor Balaguer, under the auspices of the Queen Regent. At the end of the article, there is a separate paragraph that reads:

‘We have learned from reliable sources that many of the objects in the exhibition of Filipino products, currently open in Madrid, will be ceded by their owners to this Institution, as a token of deference and gratitude to the founder of the museum library, now Minister of Overseas, to whom the realization of such an important event is due’.

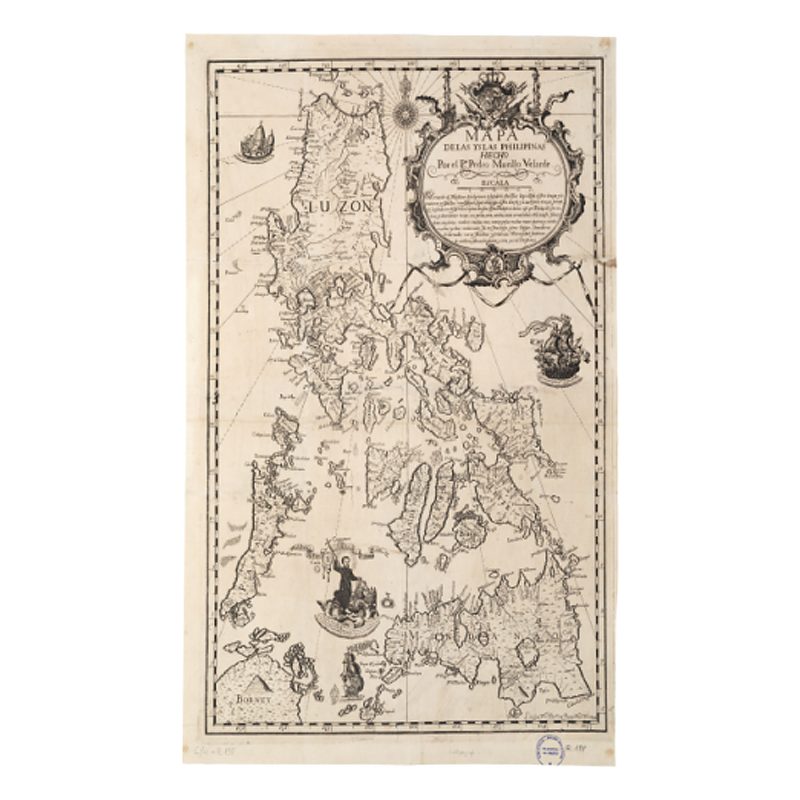

Balaguer requested duplicates of works directly from the Philippines, such as the ethnographic map of Mindanao sent to Vilanova from there (Oliva, 1887: 1). Balaguer’s correspondence and the bulletin also mention the sending of objects to Vilanova after the exhibit. Donations from the exhibition were recorded between October 1887 and February 1888, although some objects do not appear in the museum’s publications. García was one of the exhibitors who publicly donated their pieces to the BMVB collection.

The artefact MBVB-8329 was featured in the second section of the exhibition, titled ‘Population’. This second section was originally conceived as a kind of sampling of the costumes and domestic objects used by the different sectors that made up Philippine society at the time—including the Europeans living in the archipelago. However, once the event opened, it appeared as an eminently ‘ethnographic’ section, in accordance with the nineteenth-century sense of the term (Sánchez Gómez; 46). Although the explicit aim of the exhibition’s organizers, with regard to this second section, was to offer visitors from the mainland an insight into the everyday life of the native Filipinos—‘By visiting this section, those who do not know the Archipelago can form a complete judgement of the social and political way of being of its inhabitants, [since] in no better way can the character and habits of a people be studied than by coming into contact with what surrounds them in the intimate manifestations of life’ (Catalogue: 243). It must be borne in mind that at the time we find ourselves the perception that the possession of the colony is in danger is on the rise, as other imperial powers manifest an increasing interest in expanding their influence in this region of the Pacific.

Geopolitical tensions, especially after the 1885 Spanish-German conflict over the Caroline Islands, highlighted the fragility of the Spanish position in the Philippines and the urgent need to reinforce the colonial presence in the region (Sánchez Gómez: 35). Thus, the holding of the Philippines Exhibition was intended to publicly affirm Spain’s presence and influence in its Asian territories, as well as to demonstrate—or at least to perform—that the Spanish administration had achieved an exhaustive knowledge and dominion over the territory it administered and its inhabitants. The centrepiece of this demonstration of power was a human zoo in which nearly forty native people from both the northern and southern ends of the Philippine archipelago were exhibited. It is no coincidence that the people who participated in this zoo did so without exception as representatives of those groups that had most fiercely defended their independence: the processes of alteration of the Igorot peoples were linked to the colonial need to enable a common sense that presented the subjects under military harassment as deserving of the treatment they received, fostering a notion of savagery.

For the collection of artefacts, a centralized agency was set up, based in Manila, with provincial and local branches. The local boards collected the artefacts on the ground and sent them to the provincial subcommissions, which in turn sent them to Manila, from where they travelled to the mainland on board the ships of the Compañía Transatlántica, owned by Antonio López y López. As Sánchez Gómez points out, the composition of this system of artefact collection reflected the social and administrative structure of Philippine society at the time (ibidem: 44): the local boards were composed of members of the indigenous elites, while the provincial and central commissions included members of the clergy as well as civil authorities.

Estimació de la procedència

The object in question is a women’s saddle made of bejuco from the province of Camarines Sur, Philippines (formerly known as ‘Nueva Cáceres’). This object was donated by Regino Garcia y Baza, a prominent Filipino artist, botanist and forester, known for his work in the classification and display of botanical and cultural specimens during the Philippines Exhibition of 1887. The first mention of this piece is found in the Butlletí de la BMVB of December 1887, where it is recorded as part of a donation by García that included two saddles and two knives (bolos).

The possible journey of this piece begins with its inclusion in the Philippines Exhibition in 1887, held in Madrid’s Retiro Park. The exhibition was organized by Víctor Balaguer, a prominent politician who served as Spain’s Minister of Overseas. The event sought to assert Spain’s colonial presence and control over the Philippines in a context of growing geopolitical tensions. His intention was to present the archipelago as a valuable possession of the empire, showcasing cultural and natural artefacts in a framework that served colonial interests.

During the exhibition, the saddle was part of the ‘Population’ section, which was intended to show aspects of everyday Filipino life. However, this section took on an eminently ethnographic focus in order to offer European visitors an insight into the character and customs of the Filipino inhabitants. After the exhibition, Regino García y Baza publicly donated the saddle to the collection of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, in recognition of the organization of the event and of his relationship with Balaguer.

The piece was transported from the Philippines to Spain through a centralized artefact collection system based in Manila, and the objects were shipped aboard the vessels of the Transatlantic Company. This process reflected the colonial hierarchies of the time, in which local and indigenous elites were involved in the collection of artefacts under the supervision of the colonial authorities.

The inclusion of the saddle in the BMVB collection is an example of the cultural exchange and transfer of objects that took place during the colonial period, highlighting the complexities of the interaction between colonizers and colonized. While García’s donation was part of an effort to conserve and display Filipino cultural wealth, it must also be seen in the broader context of the power dynamics and colonial narratives that characterized the period.

Possibles classificacions alternatives

With the results obtained, some fields in the inventory record of this object can be updated:

Place of production/origin: Camarines Sur (formerly known as ‘Nueva Cáceres’, Luzon Island)

Donor or seller: Regino García y Baza (1840–1916)

Date of acquisition by the institution: December 1887

Complementary sources

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas (1887). Catálogo de la exposición general de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid… el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

García y Baza, R. (s. d.). Regino García y Baza. Prabook. <https://prabook.com/web/regino.garcia_y_baza/3776028#google_vignette> [consulta: 08/08/2024].

La Ilustración. Revista Hispanoamericana (1887). Any 8, (360). Barcelona: Luis Tasso.

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Pérez, Á. (1902). Igorrotes: Estudio geográfico y etnográfico sobre algunos distritos del norte de Luzón. Imp. de «El Mercantil».

Ruiz Gutiérrez, A. (2012). Arte indígena del norte de Filipinas: Los grupos étnicos de la Cordillera de Luzón. Granada: Atrio.

Sánchez Gómez, L. Á. (2003). Un imperio en la vitrina: El colonialismo español en el Pacífico y la Exposición de Filipinas de 1887. Madrid: CSIC Press.

Taviel de Andrade, E. (1887). Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid en 1887 (2 vol.). Madrid: Imprenta de Uliano Gómez y Pérez.