Summary of results

The kurab-a-kulang armour, originally from Jolo, represents a clear example of Spanish influence on traditional Filipino weaponry. Used by the Bangsamoros of the southern Philippines, this armour not only illustrates the adaptation of European design techniques, but also symbolizes cultural resistance to colonial domination.

The armour is a testament to the Bangsamoro’s ability to adapt and resist in the face of Spanish colonial influence. Despite the impact of colonialism, local communities assimilated elements of Spanish design to create armour using local materials such as carabao horn and embossed silver. This syncretic process allowed the Bangsamoro to integrate European influences while maintaining distinctive elements of their own tradition, creating unique pieces that reflected both adaptation and resistance.

During the colonial conflict, Sultan Harun was appointed Sultan of Sulu by the Spanish governor, a move that generated tension and conflict in the Philippines. The capture of Tapul on 24 May 1887, where the armour in question was obtained, was part of a broader effort to consolidate Spanish control in the region. The Spanish displayed the armour, and other captured weapons, at the Philippines Exhibition in Madrid as proof of their military conquests.

Tapul’s armour, along with other heavy weapons, was sent to the Madrid Exhibition by the Maestranza de Manila. This institution was responsible for the manufacture, maintenance, and distribution of armament to the Spanish military forces in the Philippines. At the exhibition, the Museo de Artillería included this armour as part of its collection, along with lantakas and other weapons confiscated during the military operations in Jolo. The display of these objects was an act of cultural appropriation and propaganda by the Spanish colonizers, who sought to present Spanish rule as civilizing.

The Philippines Exhibition of the Philippine Islands, held in Madrid in 1887, was a key platform for expanding the collection of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB). As Minister of Overseas, Balaguer played a decisive role in its organization, which served to dramatize Spanish rule over the Philippines. Although the exhibition was presented as a display of everyday Filipino life, it was actually intended to reinforce Spain’s image of control and influence in its Asian dominions. Balaguer used this opportunity to acquire numerous objects and books for his collection. The presentation of a ‘human zoo’, where Filipino people were exhibited, exemplifies the cultural appropriation and manipulation of colonial narratives by the Spanish. This exhibition allowed many objects to end up in the BMVB, enriching its Filipino collection and leaving a legacy of collections that serve as testimony to the colonial dynamics of the time.

The armour of Tapul, currently in the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, is a significant piece that allows us to reflect on power relations and resistance during the colonial era. Its presence in the museum’s collection offers the opportunity to reconsider historical narratives and highlight local agencies in their struggle for cultural preservation.

The story of the kurab-a-kulang armour underlines the complexity of colonial dynamics in the Philippines. Despite colonial narratives that seek to invisibilize local contributions and resistance, this armour demonstrates the ingenuity and resilience of the Bangsamoros in their struggle to maintain their identity and traditions in the face of Spanish domination. The presence of this piece in the museum, as well as the existing documentary archive on the Philippines at the BMVB, serve as a reminder of the rich history of resistance and cultural adaptation of colonized peoples.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

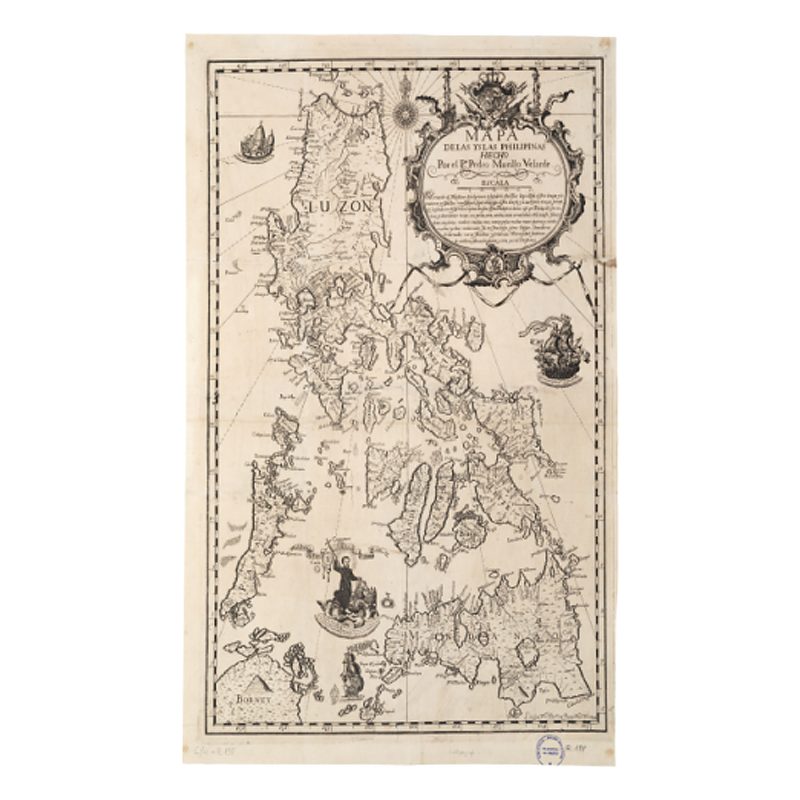

The kurab-a-kulang armour, originating from Jolo, is a prime example of Spanish influence on traditional Filipino weaponry. Used by the Bangsamoros of the southern Philippines, this armour shows a clear assimilation of Spanish design techniques, as the local natives copied the armour they had seen during their captivity by Spanish forces. Adapted to the materials available in their environment, these armours were made from carabao horn, embossed silver, metal and chain links, and often featured distinctive decorations on the chest. This process of cultural and technological synthesis allowed the Bangsamoro to combine European influences with their local traditions, creating a unique piece that reflected both resistance and adaptation in the face of colonial domination. It could be the object recorded in the museum’s old archive [ethnography, 136, panoply G, no. 6] which reads: ‘According to the label this breastplate was taken from a Moro killed in the capture of Zapul (Jolo), on 24 May 1887’.

Sultan Harun, whose full name was Muhamad Harun ar-Rashid, was appointed Sultan of Sulu by the Governor-General of the Philippines, Emilio Terrero, from 1886 until his abdication in 1893. He was born in Palawan and died in 1899. As datu (chief) of Palawan, he was instrumental in the signing of a peace treaty with the Spanish in 1878. His appointment led to a succession dispute and a new military conflict in the Philippines. After Badaruddin II’s death, two successors to the throne were proclaimed sultans at the same time. In 1885, Harun was sent to Manila to mediate and in 1886 he was appointed Sultan of Sulu. However, his appointment caused local friction and hostility. In October 1886, Harun, with Pedro Ortuoste, left for Sulu where he had to reside under Spanish protection because of local resistance. The main datus did not recognize him. In February 1887, the Governor-General declared a state of war.

On 15 April 1887, an offensive of 800 men was launched towards Maimbung (the capital of the sultanate and a holy city for the Tausug). The next day, warships approached along the coast, joining Sultan Harun and his warriors. The fortification of Maimbung was attacked by land and sea, and hand-to-hand fighting ensued. The cotta (fort) remained in the hands of the Spanish army, although casualties were heavy on both sides. Amirol Quiram, brother of the late Badaruddin II and one of the self-proclaimed sultans, managed to escape. Maimbung was destroyed, and the remains of the fortification were looted and burned. The destruction of Maimbung also aimed to cut off the supply of arms and ammunition and to ensure that Chinese merchants would establish trade relations with the new sultan, and consequently also with the Spanish. Amirol Quiram’s followers suffered heavy casualties, and much of his court was annihilated. Harun, after his victory and having set fire to the fortification, thus consolidating his power by force, continued his plan of subjugation by attacking the sultan’s panglimas, the second-ranking governors at the court.

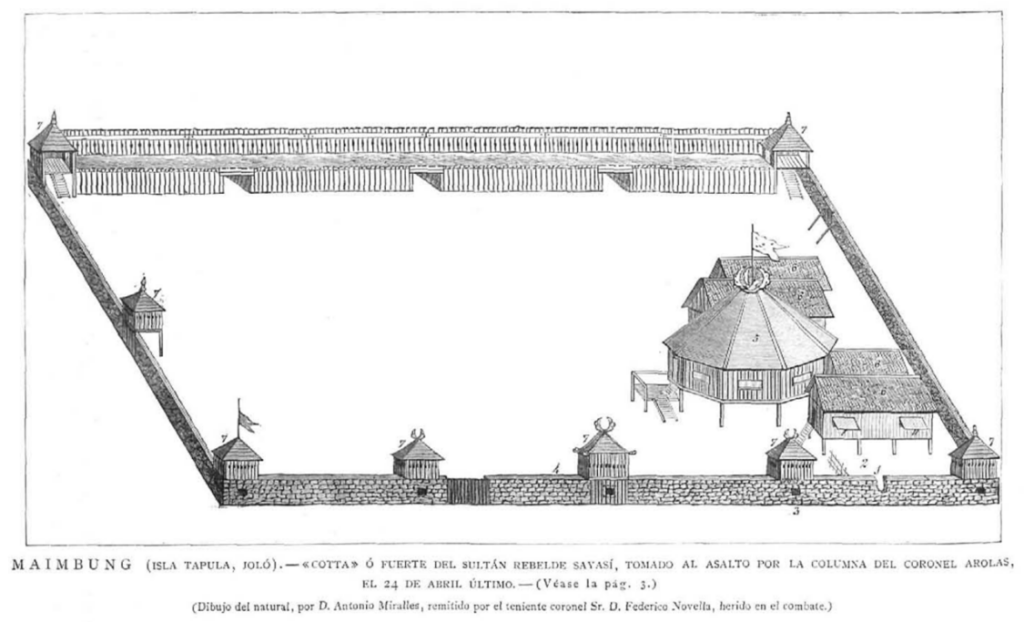

After the capture of Maimbung, they surrounded the cotta of the Alimarang panglima in Damang between 8 and 9 May. The panglima agreed to submit to the sultan, on condition that he did so in his house, in a solemn manner and in the presence of his acolytes. The next expedition headed for Patikul, but the Spanish army was ambushed. There were so many casualties that a forced retreat was necessary. For Arolas, the political and military governor of Jolo, such a setback called for a forceful response. With the cooperation of the navy, the next expedition set out for the island of Tapul, the head of a small archipelago within the Sulu archipelago. The target was the Sayari panglima, opposed to Harun’s imposition. On 24 May 1887, his fortification was destroyed, not without great difficulty, as it was a cotta four times the size of Maimbung. Moreover, the Spanish had virtually no information, as the island of Tapul had never been conquered. The panglima Sayari fought with great ferocity and died during the assault, along with ninety of his followers—it is possible that the number of casualties was even higher. While this was happening, Sultan Harun had attacked with his men the small cottas on the rest of the island. The day after Tapul was destroyed, the remaining datus on the island, as well as the Sayari survivors, took an oath of allegiance to Harun. In this operation, the Spaniards also requisitioned all heavy weaponry, arms, and other objects, before reducing the cotta to ashes (Martínez, 1988: 168). Both the capture of Maimbung and the fall of Sayari were presented to the public as the great Spanish victory over the rebellion raised by the new sultanate.

- Cotta del Panglima Sayari, Tapul, Sulu. Publicat a La Ilustración Española y Americana, núm. XXV, Madrid, 8 de juliol de 1887. En el peu original de la il·lustració, es localitza erròniament Maibung a l’illa de Tapul. Segons la descripció de la cotta a la Historia de la Piratería Malayo-Mahometana en Mindanao, Joló y Borneo, de José Montero Vidal (Madrid, 1888), aquest croquis correspon amb el fort del Panglima Sayari a Tapul.

At the Philippines Exhibition in the Retiro Park in Madrid, two exhibitors displayed armaments from the Maimbung and Tapul operations. On the one hand, Emilio Terrero himself, Governor-General of the Philippines, in the Additional section, exhibited arms and military material from the capture of Maimbung (Catalogue: 709). In the same section, the Museo de Artillería [MdA] (which at the time was located in the Retiro Park) exhibited military material seized in the operation against the Sayari panglima in Tapul.

In 1803, thanks to the impetus of the Artillery and Engineers Corps and Godoy, the Museo de Artillería officially became the Real Museo Militar, located in the Palace of Monteleón. Initially, the collection consisted of three main collections: the cabinet of the French general Marquis of Montalambert, the models assembled since 1736 in the Arsenal de Artillería in Madrid and a collection of various historical objects donated by military and noblemen. In 1841, during the reign of Isabel II, the regent General Espartero moved the museum to the Buen Retiro Palace. Two years later, in 1843, under the direction of Gil de Palacio, the first museum catalogue was published, followed by a second in 1856. In 1874, Adolfo Carrasco introduced a major change by initiating a reasoned, descriptive catalogue and by organizing the collections according to Linné’s taxonomic principles. By 1869, a Treatise on the Nomenclature of artillery material had been begun to standardize terminology. In 1904, the Boabdil pieces were brought into the Museum, prompting the creation of the Arab Room. In 1996, it was decided to relocate the museum, which today is called the Army Museum, to the fort Alcázar of Toledo.

Between 1908 and 1914, the general catalogue of the Museo de Artillería was published in four volumes. The first volume contains five lantakas from the capture of Tapul (Catálogo General del Museo de Artillería [CGMA], I: 238), which coincides with the display of five lantakas from Jolo (Catálogo: 651), as well as the flag of the Sayari panglima (CGMA, I: 315). According to the catalogue, these objects were sent by the Maestranza de Artillería de Manila and formally entered the MdA from October 1894. The Maestranza de Artillería was an institution responsible for the manufacture, maintenance and storage of armaments, munitions, and other military equipment necessary for defence and military operations (Gallegos, 2016). This organization had a series of workshops and warehouses where artillery pieces were produced and repaired, as well as the tools and wagons necessary for the services. The Maestranza had facilities dedicated to the safe storage of armaments and ammunition, protecting them from the inclemency of the weather and ensuring their availability in case of need. It played a crucial role in the distribution of military supplies to different strategic points, ensuring that the military forces had resources for their operations.

Thanks to the MdA catalogues, it has been possible to verify that the heavy weapons requisitioned during the capture of Tapul were indeed sent to the Madrid Exhibition by the Maestranza de Manila. As for the light armament (weapons, armour) that came from Jolo and was displayed at the exhibition by the MdA, it was not included in the catalogue of the military collection in 1894. It is possible that this was due to the creation of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar in parallel to the Philippines Exhibition held in Madrid. The main objective of this new museum was to disseminate the history, culture, and products of the overseas territories, especially those of the Spanish colonies in America and Asia. To this end, the museum was provided with numerous objects and publications reflecting the richness and diversity of these territories. The museum received a vast collection of objects and publications, starting with approximately six thousand volumes and objects from the Philippines Exhibition, as well as duplicates from the Ministry of Overseas (Ramírez and Domínguez, 2013: 14). In addition, the General Council of the Philippines financed the acquisition of important private libraries, such as those of Pascual Gayangos and Justo Zaragoza, increasing its collection to twenty thousand volumes. Throughout its existence, the Museo de Ultramar faced several challenges, mainly the lack of control by specialized librarians and curators, which eventually contributed to its dissolution. The museum was finally closed in 1908. The collections and objects it housed were redistributed to other institutions, such as the Museum of the Americas, the National Library of Spain (BNE), and the National Archaeological Museum.

The organization of the Philippines Exhibition, led by Víctor Balaguer as Minister of Overseas, was an opportunity to increase the BMVB’s Philippine collection with objects and books. In the institution’s bulletin of July 1887, the big news is the inauguration of the exhibition by Víctor Balaguer, under the auspices of the Queen Regent. At the end of the article, there is a separate paragraph that reads:

‘We have learned from reliable sources that many of the objects in the exhibition of Filipino products, currently open in Madrid, will be ceded by their owners to this Institution, as a token of deference and gratitude to the founder of the museum library, now Minister of Overseas, to whom the realization of such an important event is due’.

Balaguer requested duplicates of works directly from the Philippines, such as the ethnographic map of Mindanao sent to Vilanova from there (Oliva, 1887: 1). Balaguer’s correspondence and the bulletin also mention the sending of objects to Vilanova after the exhibit. Donations from the exhibition were recorded between August 1887 and February 1888, although some objects do not appear in the museum’s publications. The monthly bulletin and the correspondence between Balaguer and Joan Oliva provide valuable information on the acquisitions and allow us to identify donors, questioning the BMVB’s inventories. The reliability of the inventories of the Philippine collection is questionable, since there are numerous dating, definition and cataloguing errors.

In the rules of the organization of the exhibition, there was an article in which it was stipulated that if, after the closing of the exhibition, any objects remained unclaimed, they would be given to charity. It was also foreseen that a large part of the objects would be donated to the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar in Madrid. It is important to note that the objects from the exhibition, and published in the bulletin, arrived before the above-mentioned deadline for donation to charity. In this case, the information available in the BMVB’s old archives states that the breastplate was taken from ‘a Moro killed in the capture of Zapul [sic] (Jolo), on 24 May 1887’. This information could support the hypothesis that the piece comes from Madrid, and that it forms part of the series of objects without a defined donor that arrived in the six months after the exhibition closed and, therefore, before the date established for its possible donation to charity.

Estimation of provenance

24 May 1887, Tapul Island, Jolo Archipelago, Philippines

Eight hundred Spanish soldiers from the Jolo garrison, commanded by the military political governor of Jolo, General Arolas, disembarked on Tapul Island and attacked the cotta (local fortification) of the panglima Sayari, who was killed in action along with ninety of his followers. The heavy weaponry and bladed weapons were seized. Once reduced and destroyed, this cotta came under the control of Sultan Harun.

(?) Late May/early June 1887, Real Maestranza del Ejército, Manila, Philippines

The Real Maestranza del Ejército de Manila sends heavy armament, as well as guns, shields, and other light armament seized at the capture of Tapul to be included in the collection of the Museo de Artillería at the Philippines Exhibition.

30 June 1887, Philippines Exhibition, Retiro Park, Madrid, Spain.

In the Additional section, armament seized at the capture of Tapul is shown, on the one hand, from General Terrero, and on the other, from the Museo de Artillería.

October 1887 to February 1888 – present, BMVB, Vilanova i la Geltrú, Barcelona, Catalonia.

There is a significant number of objects from the Madrid exhibition, but there is no documentary evidence that allows us to determine the date of their entry into the BMVB. This is not the case with those private exhibitors who confirmed their donations to Balaguer, which do appear in the Butlletí de la BMVB.

The coat of mail followed a fascinating trajectory from its procurement in the Sulu archipelago to its arrival in Vilanova. Originally from Jolo, the kurab-a-kulang armour used by the Bangsamoros fused Spanish design techniques with local materials such as carabao horn and chain links. This type of armour, adopted and adapted by the Tausug, symbolized resistance against colonial authority. On 24 May 1887, during the Spanish military campaign against the Sayari panglima on the island of Tapul, this coat of mail was requisitioned. After the victory, the captured heavy armament and weapons were sent to Madrid by the Maestranza de Artillería de Manila to enrich the display of the Museo de Artillería at the Philippines Exhibition held at the Retiro Park. Subsequently, some of these objects were transferred to the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar in Madrid. After the exhibition, several objects, including the coat of mail, were transferred to Vilanova at Balaguer’s initiative to enrich the Library Museum of Vilanova, established with the aim of promoting the history and culture of the overseas territories.

Possible alternative classifications

Given that the vast majority of the information/dates given on the piece in the museum’s inventory are incorrect, a new reformulation of the inventory should be proposed that responds—correctly—to the characteristics of the piece:

Method of acquisition: spoils of war.

Place of acquisition: Tapul Island, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines

Place of production/origin: Tapul Island, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines

Collector: Spanish Army

Donor or seller: Víctor Balaguer

Classifcation group: Tausug of Tapul Island

Date of acquisition by the institution: late 1887 – early 1888

Complementary sources

(1874-1889) Expediente personal de Pedro Ortuoste. Signatura: Ultramar, 52223, exp. 43. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 41. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 43. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 46. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1886) Exposición general de las Islas Filipinas, 1887. Madrid: Impr. y fundición de Manuel Tello. Fons general, signatura: FP/1187. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

(1887) Concesión de recompensas a heridos y contusos en las operaciones sostenidas en Mindanao. Signatura 5460.7. Madrid: Archivo General Militar de Madrid [consulta: 19/03/2024].

Albi, J. (2022). Moros. España contra los piratas musulmanes de Filipinas (1574-1896). Madrid: Desperta Ferro.

Balaguer i Cirera, V. (1886-1888). Correspondencia reservada con el Gobernador general de Filipinas. Fons general, signatura 5 Ms. 113. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Víctor Balaguer (1a època, 26 de juliol de 1887), (34). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Víctor Balaguer (1a època, 26 d’agost de 1888), (47). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

Cirugeda, F. (16 de gener de 1884). Carta Filipina. Gaceta Universal. Any VII, (1.854), 06/03/1884.

Crailsheim, E. (2021). Ambivalencias modernas. Guerra, comercio y «piratería» en las relaciones entre Filipinas y los sultanatos colindantes a finales del siglo XVIII. Madrid: Polifemo.

Diario de Manila. Any XXVIII, (224), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

Donoso, I. (2023). Bichara: Moro Chanceries and Jawi Legacy in the Philippines. Palgrave Macmillan. <https://www.academia.edu/98163950/Bichara_Moro_Chanceries_and_Jawi_Legacy_in_the_Philippines> [consulta: 02/11/2024].

Espina, M. A. (1888). Apuntes para hacer un libro sobre Joló: Entresacados de lo escrito por Barrantes, Bernáldez, Escosura, Francia, Giraudier, González, Parrado, Pazos y otros varios. Manila: Imprenta y Litografía de M. Pérez, hijo.

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas (1887). Catálogo de la Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid … el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Gallegos Ruiz, E. A. de J. (gener-juny de 2017). Apuntes sobre la Real Maestranza de Artillería, Veracruz, 1762-1798. Tiempo y Espacio, XXXVI(67), 45-61.

La Oceanía Española (4 de juliol de 1887). Any XII, (152), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

Martínez Valverde, C. (juliol de 1988). Sobre la muy benemérita y sostenida acción de la Armada en Filipinas en la 2.ª mitad del pasado siglo XIX. Revista General de Marina, 157-179.

Montero y Vidal, J. (1888). Historia de la piratería Malayo-mahometana en Mindanao, Joló y Borneo. Fons general, signatura SL 5725-5726. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Museo Militar de Artillería (1908-1914), Catálogo General del Museo de Artillería. Madrid: Imprenta de Eduardo Arias.

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Ramírez Martín, Susana María i Domínguez Ortega, Montserrat (2013). Custodia de documentos sobre América Latina: El Museo-Biblioteca de Ultramar. Anuario Americanista Europeo, (11), 9-24. Sección Fondos. <https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00957437/document> [consulta: 02/08/2024].

Saleeby, N. M. (1908). The History of Sulu. Filipines: Bureau of Printing.

—(2021). Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion. Txèquia: Good Press.

Sánchez Gómez, L. Á. (2003). Un imperio en la vitrina: El colonialismo español en el Pacífico y la Exposición de Filipinas de 1887. Madrid: CSIC Press.

Taviel de Andrade, E. (1887). Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid en 1887 (2 vol.). Madrid: Imprenta de Uliano Gómez y Pérez.