Summary of results

The piece under study is a small copper pot or casserole classified as having been made by the Igorots of Juan (Lepanto) in 1865, using only two stones as tools. This pot is registered in the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB) but there is no clear information regarding its arrival. The Igorots are a cultural group from the mountainous regions of northern Luzon in the Philippines with a rich tradition of mining minerals such as copper, which they used mainly to create ornaments and tools. The Lepanto Political-Military Command, established in 1858, is located in the territory of the Kankanay Igorots, who share cultural characteristics with other Igorot groups. They were known for resisting Spanish incursions attempting to exploit their mineral resources during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Igorot cultural practices included legends, such as the copper pot, associated with the origin of headhunting. The pot on display at the BMVB probably came to Vilanova i la Geltrú through Víctor Balaguer, who managed the acquisition of many objects from the Philippines Exhibition of 1887, including the private collection of Juan Álvarez Guerra. The latter, a politician and writer, presented a wide variety of Filipino objects in the additional section of the exhibition, among which was the Igorot copper pot, which is recorded as the only piece of this type exhibited according to the exhibition catalogue.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The piece under study is a small copper pot or casserole, which has a label attached to it that reads: ‘Pot made with no other instrument than two stones, one serving as an anvil and the other as a hammer by the Igorots of Juan (Lepanto). Philippines, built in 1865’. It appears in the old BMVB record, along with its dimensions, but without any further information that might clarify how it arrived at the museum.

The Igorots are a cultural group that encompasses different ethnolinguistic groups living in the mountainous regions of Northern Luzon, in the Philippines. Jenks explains that the word ‘Igorot’ means ‘people from the mountains’ in several languages of Northern Luzon. According to the text, the term is composed of the root ‘-gorot’, which means ‘mountain range’ in Tagalog, and the prefix ‘i-’, which denotes ‘inhabitant of’ or ‘people of’ (1905: 28). This term is applied to a large group of people living in the mountainous areas of northern Luzon and has been adopted as the general designation for the peoples of these regions. Jenks mentions that there are at least eight main groups among the Igorots, although he notes that there is much diversity in the dialects and cultures of these groups. Each has its own dialect and some cultural differences that distinguish them from one another, although they all share the common cultural basis of being mountain farmers and, in the past, practitioners of headhunting.

The Political-Military Command of Lepanto was an administrative division created in 1858, the territory of which is currently located in the provinces of Ilocos Sur, Ilocos Administrative Region (Region I) and Benguet, and Mountain Province in the Cordillera Administrative Region, also called (CAR Region). The Igorots of Lepanto reportedly belong to the ethnolinguistic group known as the Kankanay or Kankanai and share cultural characteristics with the Igorots of Benguet.

The culture of the Lepanto Igorots was characterized by a combination of agricultural and metallurgical traditions. The Igorots were known for their skill in extracting minerals, including copper, using traditional methods. They used rudimentary tools, such as wooden sticks with iron points, to extract ore from the seams. Once extracted, the ore was ground on large stone slabs and then washed in creeks. Mining was a central economic activity for the Igorots of Lepanto, and although they faced Spanish incursions during the 17th and 18th centuries, they resisted the colonizer’s attempts to control their mineral resources. This resistance continued throughout the 19th century, when conflicts became more devastating due to continued colonial pressure that not only sought to exploit the copper and gold mines, but also the total subjugation of the Igorots to the Spanish administration.

Copper, which is abundant in this region, was used by the Igorots before the arrival of the Spanish. They didn’t only make tools and weapons, but they also created personal ornaments, such as rings and earrings, which hold great cultural and symbolic value (García, 1887). It does not seem to be the material usually used for the manufacture of pots and pans for everyday use, because they were usually made of ceramic, and there are very few examples of copper pots preserved in museums around the world: in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, and in the Geneva Ethnography Museum. The information in both cases is minimal and does not allow definitive conclusions to be drawn.

In Jenks’ book, however, there is a legend about a copper pot that explains the origin of head-chopping among the Igorots. The story goes that the Moon, called Ka-bi-gato, was making a large copper pot. As she worked, the copper was soft and malleable, like a potter’s clay. A son of the Sun, Chal-chal, watched her as she modelled the pot. Seeing him, the Moon struck him and cut off his head. The Sun came over, picked up the child and put his head back on, bringing him back to life. The Sun then told the Moon that, as a result of her action, humans would start cutting each other’s heads off.

In Igorot society, the practice of cutting off heads played a significant role in social, cultural, and religious terms. It was perceived as a ‘life debt’ that had to be settled to balance honour and justice after a murder. In addition, it functioned as a test of courage and masculinity, conferring an elevated status on those who participated. Although it was not strictly necessary for ceremonies such as marriage, it was linked to rituals and festivities that reinforced social cohesion and community identity. Symbolically, it was believed that the spirits of enemies could protect the village and bring prosperity. The practice was deeply rooted in Igorots legends and myths, reflecting its importance in the world view of these communities.

To understand how the piece arrived in Vilanova i la Geltrú, it is essential to explore the role of Víctor Balaguer and the impact of the Philippines Exhibition of 1887 in Madrid. In his third term as Minister of Overseas (from 10 October 1886 to 14 June 1888), Balaguer promoted important reforms in tax, tariff, public works and transport, and communications policies, as well as a progressive extension of peninsular legislation in accordance with his assimilationist positions. He also promoted the creation of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, in Madrid—which he himself directed until his death—and the Museo Biblioteca de Filipinas, in Manila, and was the true architect of the organization of the Philippines Exhibition, held from 30 June to 30 October 1887.

Madrid’s Retiro Park was the venue for the exhibition. The Crystal Palace, also known at the time as the ‘Pabellón de Cristal’ (literally, Crystal Pavilion), was built for the exhibition. And although it was planned to be converted into the headquarters of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, this never happened. The exhibition displayed a group of between forty and fifty people from the Philippines along with local objects, products, and plants, recreating the ‘natural habitat’ of the indigenous Filipinos in the palace lake. This was the first human zoo in Spain in modern times. Following its success in terms of attendance, there were private companies that organized new exhibitions of people from outside Europe, both from Spanish colonies and from other countries, a practice that existed until 1942.

In the Butlletí de la BMVB of July 1887, page 5, the big news is the inauguration of the exhibition by Víctor Balaguer, under the auspices of the Queen Regent. At the end of the article, there is a separate paragraph that reads:

‘We have learned from reliable sources that many of the objects in the exhibition of Filipino products, currently open in Madrid, will be ceded by their owners to this Institution, as a token of deference and gratitude to the founder of the museum library, now Minister of Overseas, to whom the realization of such an important event is due’.

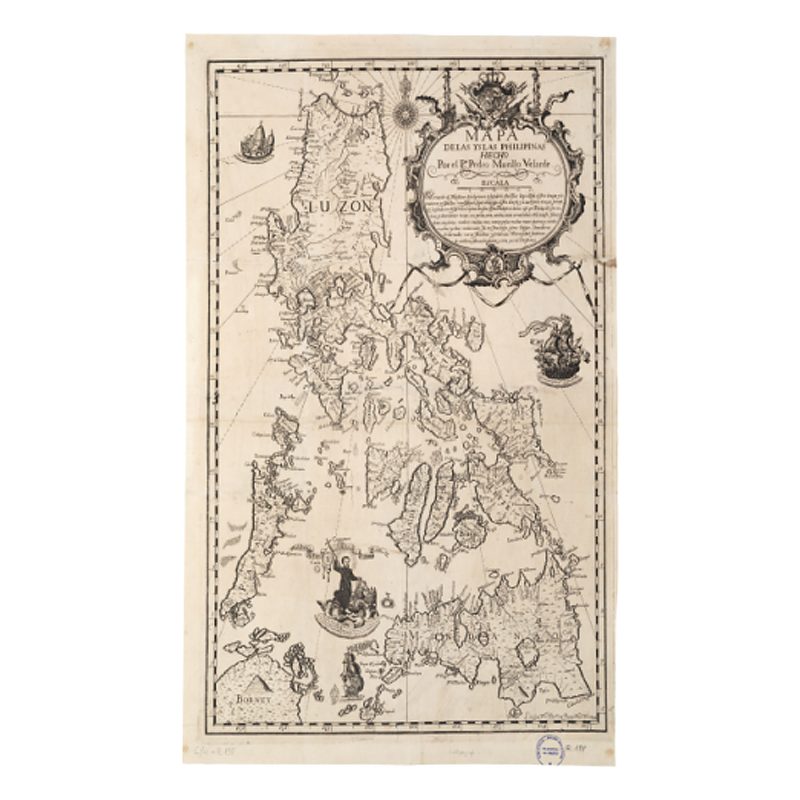

Balaguer requested duplicates of works directly from the Philippines, such as the ethnographic map of Mindanao sent to Vilanova from there (Oliva, 1887: 1). Balaguer’s correspondence and the bulletin also mention the sending of objects to Vilanova after the exhibit. Donations from the exhibition were recorded between October 1887 and February 1888, although some objects do not appear in the museum’s publications. The monthly bulletin and the correspondence between Balaguer and Joan Oliva provide valuable information on the acquisitions and allow us to identify donors, questioning the BMVB’s inventories. The reliability of the inventories of the Philippine collection is questionable, since there are numerous dating, definition, and cataloguing errors.

At the 1887 exhibition, Juan Álvarez Guerra presented his private collection in the Additional section, which was advertised as a special collection. It included all kinds of objects and specimens from a wide variety of sources in the Philippine archipelago. Such was the variety of his collection that it is referenced in multiple sections of the exhibition catalogue. The Álvarez Guerra objects in the second section include a copper pot used by Igorots (Catalogue: 607). Juan Álvarez Guerra Castellanos (1843–1905), a politician, writer, and traveller of La Mancha origin, was a magistrate of the Audencia de Manila.

He was also the author of the book Viajes por Filipinas, in three volumes: De Manila a Marianas, De Manila a Tabayas, and De Manila a Albay, published in Manila between 1871 and 1887. Alvarez Guerra was a member of the Comisaría Regia de la Exposición, and a member of the Consejo de Filipinas and the Consejo de Ultramar, as well as a well-known scholar of the Philippines who wrote articles on the exhibition. Previously, he had been the editor of the Revista de la Exposición de Objetos del Pacífico, held at the Botanical Garden in Madrid in 1866, on the collections of the Scientific Commission to the Pacific.

We know that he was one of the first collectors to open a private museum in the Spanish capital, located in his private home in the Plaza del Progreso, around 1881 (La Ilustración Española y Americana, no. XXXVII, 8 October 1881: 194). There he exhibited his collection of objects and specimens from the archipelago. The collection presented at the 1887 exhibition included all the objects and specimens exhibited in his private museum. His collection included minerals, skulls, ornaments, household utensils, weapons, stuffed animals, plants, wood, handicrafts, and works of art, among others. Álvarez Guerra was also criticized by contemporary figures, such as the combative ilustrado López Jaena, for his orientalist and paternalistic view of the Philippines (Sánchez Gómez: 128).

Despite having resided there for a considerable time, he was accused of not fully understanding the customs and cultures of the archipelago. He was questioned for his tendency to impose his criteria over those of the colonial authorities and for presenting information considered false or misinterpreted about Philippine artefacts in the exhibition. Álvarez Guerra’s works were seen by some of his contemporaries as lacking significant literary or scientific value. Both his approach and the criticisms of his work reflect the tension between the Spanish colonial perspective and the growing Filipino consciousness and criticism during this period.

As the pot presented by Álvarez Guerra was the only one exhibited in Madrid according to his own catalogue, we can conclude that it is indeed the pot in the BMVB.

Estimation of provenance

The small copper pot from the BMVB was presumably acquired through the private collection of Juan Álvarez Guerra, exhibited at the 1887 Philippines Exhibition in Madrid. The label on the pot indicates that it was made in 1865 by the Igorots of Juan, in Lepanto, using only two stones as tools, reflecting the traditional craftsmanship techniques that we know about them. The Lepanto Igorots belonged to the Kankanay or Kankanai ethnolinguistic group, which shares cultural characteristics with the Benguet Igorots. Known for their skill in working copper, they used it mainly to make ornaments and tools, although the creation of copper pots was unusual, with pottery being the most common material for making such utensils.

The pot came to Vilanova i la Geltrú as part of a series of donations and acquisitions made by Víctor Balaguer after organizing the 1887 exhibition. Balaguer, who was Minister of Overseas and promoter of the event, managed the transfer of many objects exhibited at the BMVB, which were donated as a token of gratitude to him and his cultural work. The copper pot is considered part of this legacy, linked to the collection presented by Álvarez Guerra—which included the only Igorots copper pot documented in the exhibition catalogue.

Possible alternative classifications

Based on the results of the present research, the following data can be updated in the inventory:

Brief institutional description: In the inventory, the context about the Kankanai Igorots, inhabitants of the Lepanto area, would have to be further expanded. Because of the paucity of information on Igorots copper pots, it cannot be confirmed with certainty that this is a kitchen or everyday object.

Place of acquisition: Juan, Lepanto Political-Military Command (between the provinces of Ilocos Sur, Benguet and Mountain Province, Luzon, Philippines).

Place of production/origin: Juan, Comandancia Político-Militar de Lepanto (between the provinces of Ilocos Sur, Benguet and Mountain Province, Luzon, Philippines).

Collector: Juan Álvarez Guerra

Donor or seller: Víctor Balaguer

Classification group: Kankanay or kankanai

Complementary sources

Álvarez Guerra, J. (1866). Revista de la Exposición de Objetos del Pacífico en 1866. Madrid: Imprenta a cargo de Gregorio Juste.

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Víctor Balaguer (1a època, 26 de juliol de 1887), (34). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

«Cooking pot», Mapping Philippine Material Culture, <https://philippinestudies.uk/mapping/items/show/6415> [consulta: 05-08-2024].

«Copper pot», Mapping Philippine Material Culture, <https://philippinestudies.uk/mapping/items/show/13231> [consulta: 05-08-2024].

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas (1887). Catálogo de la exposición general de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid… el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Fernández Palacios, J. M. (2024). La crisis de las islas Carolinas de 1885 analizada desde Filipinas. Ayer. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, 134(2), 169-193. <https://www.revistasmarcialpons.es/revistaayer/article/view/fernandez-la-crisis-de-las-islas-carolinas-de-1885/2631>.

La Ilustración. Revista Hispanoamericana (1887). Any 8, (360). Barcelona: Luis Tasso.

La Ilustración española y americana (8 d’octubre de 1881). Any XXV, (37), 2.

Jenks, A. E. (1905). The Bontoc Igorot. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing. <https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3308>.

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Pérez, Á. (1902). Igorrotes: Estudio geográfico y etnográfico sobre algunos distritos del norte de Luzón. Imp. de «El Mercantil».

Pérez-Rubín Feigl, J. (2014). Las colecciones marinas institucionales no docentes en Madrid (1776-1893). Boletín de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural, secció Aula, Museos y Colecciones, 1, 91-112.

Ruiz Gutiérrez, A. (2012). Arte indígena del norte de Filipinas: Los grupos étnicos de la Cordillera de Luzón. Granada: Atrio.

Sánchez Gómez, L. Á. (2003). Un imperio en la vitrina: El colonialismo español en el Pacífico y la Exposición de Filipinas de 1887. Madrid: CSIC Press.

Taviel de Andrade, E. (1887). Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid en 1887 (2 vol.). Madrid: Imprenta de Uliano Gómez y Pérez.