Summary of results

The first known record of this piece is found in the old register of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, where it is described as ‘anito, human figure, yellowish wood, seated on the floor with arms folded on the knees’. However, the current categorization of the piece in the BMVB defines it as ‘Divinity Protector of Rice (Bul-ul)’.

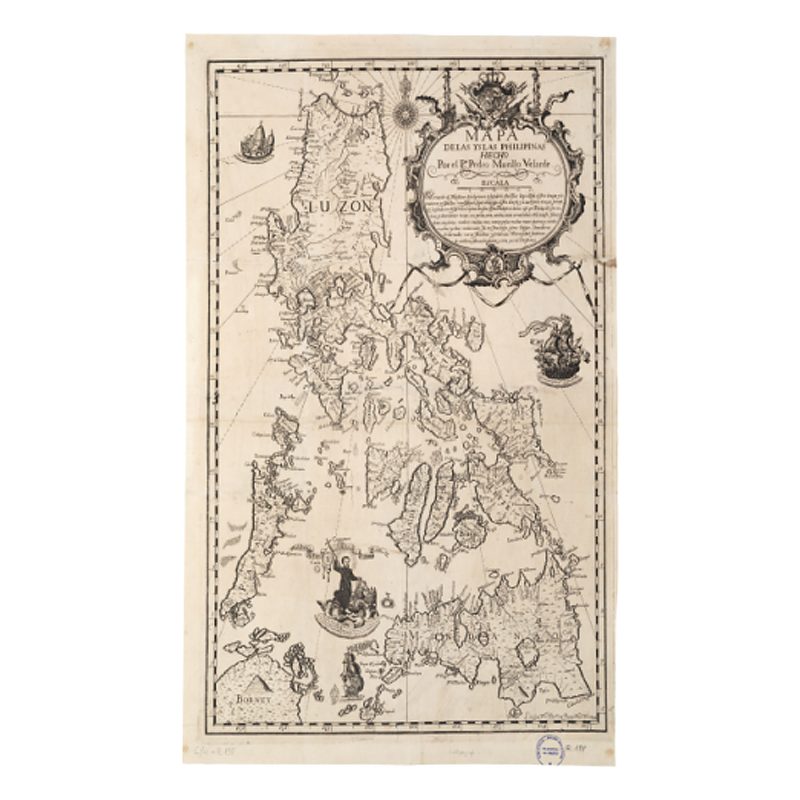

The object in question is a bulul or bulol, a carved and enshrined figure of great importance to the Ifugao culture of the Cordillera mountains in Luzon, Philippines. These figures are usually made of narra, ipil or molave wood and represent deceased ancestors. The bululs are associated with Ifugao agricultural practices, especially rice farming, and are considered to be protectors of crops. Although there are variations in shape and style depending on the region of Ifugao from which they originate, this bulul may originate from the central area around Banaue, given its design and characteristics.

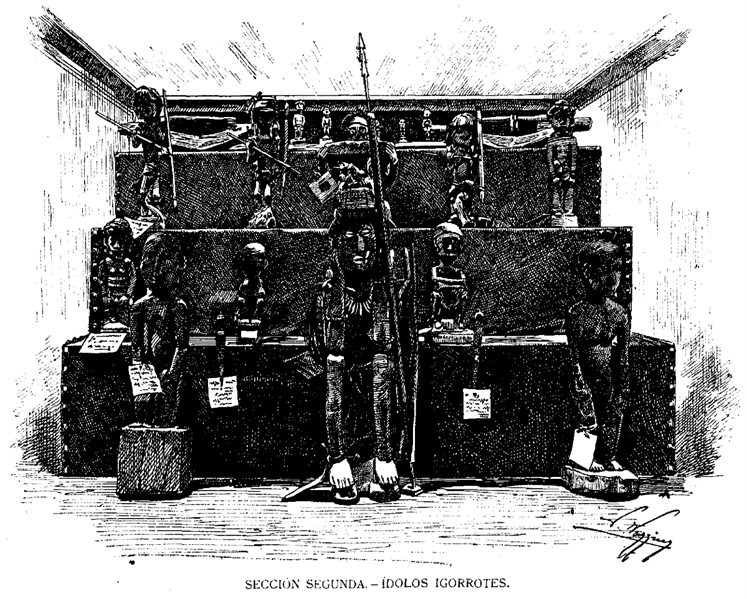

In the second section of the Philippines Exhibition in Madrid in 1887, the provincial subcommissions of Bontoc, Tiangan, Lepanto, and Nueva España, together with the Central Commission of Manila presented, among other objects, wood carvings of both spiritual content (bulol) and of different Igorot human types, which were displayed as anitos.

European museums have routinely categorized wood carvings from northern Luzon as anitos. It is a term that was used by the Spanish colonizers to refer generically to the religious representations of the Igorot and other ethnic Filipino peoples, based on the Eurocentric and Christian perception that considered indigenous religions to be primitive and superstitious.

The categorization of these figures as anitos was a simplification that did not reflect the actual complexity of local beliefs. Anthropologists such as Albert Ernest Jenks described the term ‘anito’ in Filipino contexts as a reference to ancestor spirits rather than specific physical figures. Even so, in European exhibitions, these carvings were presented as mere ethnographic curiosities without adequate explanation.

Víctor Balaguer, a prominent Catalan politician and intellectual, played a key role in the organization of the Madrid exhibition. As Minister of Overseas and founder of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, he was one of the main driving forces behind the collection and exhibition of colonial artefacts. Balaguer’s correspondence and the Butlletí de la BMVB mention the sending of objects to Vilanova after the exhibition. Donations from the exhibition were recorded between October 1887 and February 1888, although some objects did not appear in the museum’s publications. Balaguer facilitated the transfer of these objects to Vilanova, thereby consolidating his role as a key promoter of cultural dissemination and the Filipino legacy in Europe.

The collection of objects for the exhibition was organized through a centralized system in Manila, with provincial and local branches. Local boards, composed of members of the indigenous elites, collected objects in the field and sent them to provincial subcommissions, which then forwarded them to Manila for transport to Spain. This process reflected the social and administrative structure of the time, in which the colonial authorities and the clergy played an important role.

The exhibition included a wide range of artefacts intended to provide an understandable insight into Filipino life and culture. However, the descriptions and contextualization of these objects were often insufficient, limiting the public’s understanding of the true cultural and religious complexity of the Philippines.

The Philippines Exhibition of 1887 had a significant impact on public perception and Spanish colonial policy. It was an attempt to reassert colonial control and demonstrate Spanish knowledge and dominance over the Philippines. The inclusion of a human zoo, where people from the regions most resistant to Spanish rule were exhibited, reflected the need to justify colonial presence and actions. The arrival of the piece in Vilanova and its subsequent exhibition symbolize the legacy and contradictions of Spanish colonialism, as well as the interest in documenting and preserving cultures that were altered and reinterpreted through a colonial lens.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The first known record of this piece is found in the old register of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, where it is described as ‘anito, human figure, yellowish wood, seated on the floor with arms folded on the knees’.

Wood carvings from the north of the island of Luzon are usually catalogued by European museum institutions as anitos. Both in the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum and in other state museums (the National Museum of Anthropology of Madrid, the Oriental Museum of Valladolid, and the Museum of Ethnology and World Cultures of Barcelona) and European museums (the British Museum of London and the Museum of Ethnography of Stockholm), we find wood carvings made in the north of the island of Luzon under this same category.

During the colonial era, the Spanish viewed the religions of the Igorot peoples, as well as other indigenous religions present in the Philippines, as inferior, primitive, and pagan. This approach was based on a Eurocentric and Christian worldview that viewed indigenous religious beliefs and practices as superstitions to be eradicated or replaced by Christianity. This also affected the categorization of their representations. In the Catalogue of the Philippines Exhibition in Madrid, in describing the religious beliefs of the Igorot peoples, it is stated:

‘They hold the idea of a Supreme Being and various secondary divinities, above all, the anitos, good or evil spirits who reward or punish men, and who are usually represented by rude little wooden idols’ (Catalogue: 115).

According to Albert Ernest Jenks, an American anthropologist who conducted an ethnography among the Bontok in 1902, ‘anito’ is ‘the general name for the soul of the dead’ (Jenks, 1905: 196). The author notes this presence as an active social force among the Bontok, explaining that all injuries, accidents, illnesses, and deaths were considered to be the direct product of these entities. He also describes how they were extracted from diseased bodies by specialized persons—Jenks uses the word ‘shaman’ to refer to them. It is fair to say, however, that there is no reference to any figure designated by this name in the text, and in the entire book we only find a photograph with a caption that reads: ‘Anito head post in a ko’-mis’. Pérez states that the inhabitants of Tutucan, a settlement in the northeast of the then district of Bontoc ‘are more fond than those of other [rancherías, small rural settlements] of placing rough wooden statues called anitos on the doors of their palay barns and in the fields,’ (Pérez, 1902: 220), but at no time does he mention the fact that these figures wore clothing or had any kind of accessory. Although it is probably true that certain statues were identified as anitos by some inhabitants of the Cordillera, we do not believe that this was the case with the artefacts that today are kept under this categorization in the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum in Vilanova i la Geltrú. In this sense, the current categorization of the present piece as ‘Divinity Protector of rice (Bul-ul)’ is less problematic than that of the ancient record.

The bulul (also bulol) is a carved and enshrined figure of great importance to the Ifugao culture of the Cordillera mountains in Luzon, Philippines. These figures, usually made of narra, ipil or molave wood, represent deceased ancestors and are created in pairs. Although bululs are essential figures in the Ifugao tradition, they can be difficult to differentiate by gender, as anatomical details, such as genitalia, are often not clearly carved. Bulul figures are intrinsically linked to Ifugao agricultural practices, especially rice farming, which is the basis of their livelihood. Bululs are considered protectors of rice crops and are believed to safeguard the grain from pests and theft. They are stored in granaries and, on special occasions, are adorned with royal jewellery or coloured beads. Bululs are more than just idols; they are a tangible manifestation of Ifugao devotion to their religious beliefs and ways of life. Bululs vary in form and style according to their geographical origin within the Ifugao region (Dancel, 1989: 3). These differences in representation reflect not only artistic talent and local traditions, but also the ceremonial and symbolic function of the figures:

Hapao-Hunduan bululs are usually in an upright position, with their hands touching or covering their knees. This posture is characteristic of figures from the western Ifugao region.

Kambulu-Batad bululs are known to be in a seated position. They are finely carved and sometimes feature details such as eyes and mouths made of cowrie shells. This attention to detail suggests a higher level of artistic skill in northern Ifugao.

Kababuyan, Banaue, Hingyon, and Mumpolya bululs may be in a seated or upright position and have a mixed expression. They often have European facial features, indicating a different influence or style within the central region.

The bululs from Kiangan in southern Ifugao are characterized by an upright position, with the hands extended parallel to the legs. They are distinguished by a more rudimentary carving, suggesting a rather functional than aesthetic approach to their creation.

Bululs, figures tallades i consagrada de gran importància en la cultura ifugao a la segona secció de l’Exposició General de les Illes Filipines a Madrid el 1887.

The variations in posture and facial details of the bululs not only indicate their regional provenance, but also reflect the cultural diversity within the Ifugao community. Each type of bulul has its own meaning and purpose in agricultural and ceremonial rituals, being a representation of the link between the Ifugao, their ancestors and their agricultural deities. The piece under study—as categorized by researcher Dancel, of the National Museum of the Philippines—may have come from the central Ifugao area around Banaue.

Five organizations and one private collector submitted carvings from northern Luzon: the Central Commission of Manila and the provincial subcommissions of Bontoc, Tiangan, Lepanto, and Nueva España. The private collector was the military officer José Coronado Ladrón de Guevara (see MuEC reports for more information). Artefact MBVB-2526 was probably among the different anitos exhibited in group 21, in the second section of the exhibition entitled ‘Population’, and sent by the above-mentioned subcommissions.

Be that as it may, in the case of the bululs, because of their spiritual component, it seems unlikely that they were made in a serial manner like other carved figures of Igorot human types exhibited in the same section, which does not preclude the possibility that they were commissioned specifically for the exhibition. The denomination chosen by the exhibitors of the show may have been driven by the intention to feed colonial curiosity for exotic religions, it also may have been designed to meet the expectations of the exhibition’s attendees by offering an exoticized view of the peoples of northern Luzon.

The second section of the Madrid exhibition was originally conceived as a kind of sampling of the costumes and domestic objects used by the different sectors that made up Philippine society at the time—including the Europeans living in the archipelago. However, once the event opened, it appeared as an eminently ‘ethnographic’ section, in accordance with the nineteenth-century sense of the term (Sánchez Gómez; 46). Although the explicit aim of the exhibition’s organizers, with regard to this second section, was to offer visitors from the mainland an insight into the everyday life of the native Filipinos—‘By visiting this section, those who do not know the Archipelago can form a complete judgement of the social and political way of being of its inhabitants, [since] in no better way can the character and habits of a people be studied than by coming into contact with what surrounds them in the intimate manifestations of life’ (Catalogue: 243). It must be borne in mind that at the time we find ourselves the perception that the possession of the colony is in danger is on the rise, as other imperial powers manifest an increasing interest in expanding their influence in this region of the Pacific.

Geopolitical tensions, especially after the 1885 Spanish-German conflict over the Caroline Islands, highlighted the fragility of the Spanish position in the Philippines and the urgent need to reinforce the colonial presence in the region (Sánchez Gómez: 35). Thus, the holding of the Philippines Exhibition was intended to publicly affirm Spain’s presence and influence in its Asian territories, as well as to demonstrate—or at least to perform—that the Spanish administration had achieved an exhaustive knowledge and dominion over the territory it administered and its inhabitants. The centrepiece of this demonstration of power was a human zoo in which nearly forty native people from both the northern and southern ends of the Philippine archipelago were exhibited. It is no coincidence that the people who participated in this zoo did so without exception as representatives of those groups that had most fiercely defended their independence: the processes of alteration of the Igorot peoples were linked to the colonial need to enable a common sense that presented the subjects under military harassment as deserving of the treatment they received, fostering a notion of savagery.

The arrival of this piece in Vilanova is due to the founder of the BMVB, Víctor Balaguer. Víctor Balaguer i Cirera (1824–1901) was a Catalan politician, writer, journalist, and historian. In 1884, he opened the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum in Vilanova i la Geltrú, which became an institution that offered library, newspaper library, museum, and teaching centre services. He served a third term as Minister of Overseas (from 10 October 1886 to 14 June 1888), promoting important reforms in tariff policy, public works and transport, and communications. Balaguer also promoted the creation of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, in Madrid—which he directed until his death—and the Museo Biblioteca de Filipinas, in Manila. At the same time, Balaguer was the true architect of the organization of the Philippines Exhibition, held from 30 June to 30 October 1887, in the Retiro Park in Madrid.

In the institution’s bulletin of July 1887, page 5, the big news is the inauguration of the exhibition by Víctor Balaguer, under the auspices of the Queen Regent. At the end of the article, there is a separate paragraph that reads:

‘We have learned from reliable sources that many of the objects in the exhibition of Filipino products, currently open in Madrid, will be ceded by their owners to this Institution, as a token of deference and gratitude to the founder of the museum library, now Minister of Overseas, to whom the realization of such an important event is due’.

Balaguer requested duplicates of works directly from the Philippines, such as the ethnographic map of Mindanao sent to Vilanova from there (Oliva, 1887: 1). Balaguer’s correspondence and the bulletin also mention the sending of objects to Vilanova after the exhibit. Donations from the exhibition were recorded between October 1887 and February 1888, although some objects do not appear in the museum’s publications. The monthly bulletin and the correspondence between Balaguer and Joan Oliva provide valuable information on the acquisitions and allow us to identify donors, questioning the BMVB’s inventories. The reliability of the inventories of the Philippine collection is questionable, since there are numerous dating, definition, and cataloguing errors. In the rules of the organization of the exhibition, there was an article in which it was stipulated that if, after the closing of the exhibition, any objects remained unclaimed, they would be given to charity.

The Philippines Exhibition held in Madrid in 1887 had a notable impact on public perception and Spanish colonial policy. This exhibition not only served to communicate military successes in the Philippines but also facilitated the integration and dissemination of exotic colonial material, such as weaponry and cultural artefacts, in a European context. So much so that objects from other Spanish colonies, not just the Philippines, were also displayed. The additional section of the exhibition featured two exhibitors who did so. On the one hand, the National Archaeological Museum presented a large collection of objects from the defunct Museo Ultramarino, mostly from the Philippines, although it also included objects from Puerto Rico (Catalogue: 636) and Fernando Poo (Catalogue: 642 and 644). On the other hand, the Museo de Artillería, among its extensive arms collections, presented numerous objects from the Caroline Islands, which were part of the Spanish East Indies.

The selection of objects for the exhibition included a wide range of items ranging from ethnographic artefacts, ship and house models, to samples of textiles, personal ornaments, weapons, and religious art pieces. These objects were intended to provide a comprehensive overview of Filipino life and culture, as well as of the Spanish colonial presence in the archipelago. However, the descriptions and contextualization of these objects were often insufficient, limiting the public’s understanding of the true cultural and religious complexity of the Philippines.

Estimation of provenance

The object in question is a bulul or bulol, a carved and enshrined figure of great importance to the Ifugao culture of the Cordillera mountains in Luzon, Philippines. These figures are usually made of narra, ipil or molave wood and represent deceased ancestors. The bululs are associated with Ifugao agricultural practices, especially rice farming, and are considered to be protectors of crops. Although there are variations in shape and style depending on the region of Ifugao from which they originate, this bulul may originate from the central area around Banaue, given its design and characteristics.

The first known record of this piece is found in the old register of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum, where it is described as ‘anito, human figure, yellowish wood, seated on the floor with arms folded on the knees’. European museums have routinely categorized wood carvings from northern Luzon as anitos. A term that was used by the Spanish colonizers to refer generically to the religious representations of the Igorot and other ethnic Filipino peoples.

During the Philippines Exhibition held in Madrid in 1887, several organizations and a private collector exhibited carved figures from northern Luzon. Among the exhibitors were the Central Commission of Manila and the provincial subcommissions of Bontoc, Tiangan, Lepanto and Nueva España, as well as the private collector José Coronado Ladrón de Guevara. It is likely that artefact MBVB-2526 was part of the anitos exhibited in group 21 and sent by these subcommissions to the second section of the exhibition, dedicated to ‘Population’.

Víctor Balaguer—founder of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum and Minister of Overseas at the time of the exhibition—played a crucial role in the organization of the event and in the transfer of objects to Vilanova. According to BMVB records, many objects from the exhibition were given to the institution as a token of deference and gratitude to Balaguer. His interest in integrating exotic material from the colonies into the European context was evident in the request for duplicates of works directly from the Philippines and in the donations recorded between October 1887 and February 1888.

The initial name ‘anito’ for the bulul may have been influenced by the exhibitor’s intention to feed colonial curiosity about exotic religions by showing an exoticized view of the peoples of northern Luzon. The Philippines Exhibition served not only to showcase military and cultural successes in the Philippines, but also to assert Spain’s presence in the region, against a backdrop of geopolitical tensions and the growing interest of other imperial powers in the Pacific. The inclusion of bulul in the BMVB as the ‘Divinity Protector of Rice’ reflects a more accurate recognition of its cultural and religious significance in the Ifugao tradition.

Possible alternative classifications

A review of the museum’s inventory is required in order to accurately reconstruct and contextualize the date of entry and provenance of the piece in question. Firstly, we know that the date of entry recorded in the museum’s inventory (1884) is incorrect, as the piece comes from the Philippines Exhibition held in 1887. We can therefore assume that the correct date of entry for this piece is 1887.

Complementary sources

Dancel, M. M. (1989). The Ifugao wooden idol. SPAFA Digest, 10(1), 3-5.

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas (1887). Catálogo de la exposición general de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid… el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Fernández Palacios, J. M. (2024). La crisis de las islas Carolinas de 1885 analizada desde Filipinas. Ayer. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, 134(2), 169-193. <https://www.revistasmarcialpons.es/revistaayer/article/view/fernandez-la-crisis-de-las-islas-carolinas-de-1885/2631>.

Jenks, A. E. (1905). The Bontoc Igorot. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing. <https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3308>.

La Ilustración. Revista Hispanoamericana (1887). Any 8, (360). Barcelona: Luis Tasso.

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Pérez, Á. (1902). Igorrotes: Estudio geográfico y etnográfico sobre algunos distritos del norte de Luzón. Imp. de «El Mercantil».

Ruiz Gutiérrez, A. (2012). Arte indígena del norte de Filipinas: Los grupos étnicos de la Cordillera de Luzón. Granada: Atrio.

Sánchez Gómez, L. Á. (2003). Un imperio en la vitrina: El colonialismo español en el Pacífico y la Exposición de Filipinas de 1887. Madrid: CSIC Press.

Taviel de Andrade, E. (1887). Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid en 1887 (2 vol.). Madrid: Imprenta de Uliano Gómez y Pérez.