Summary of results

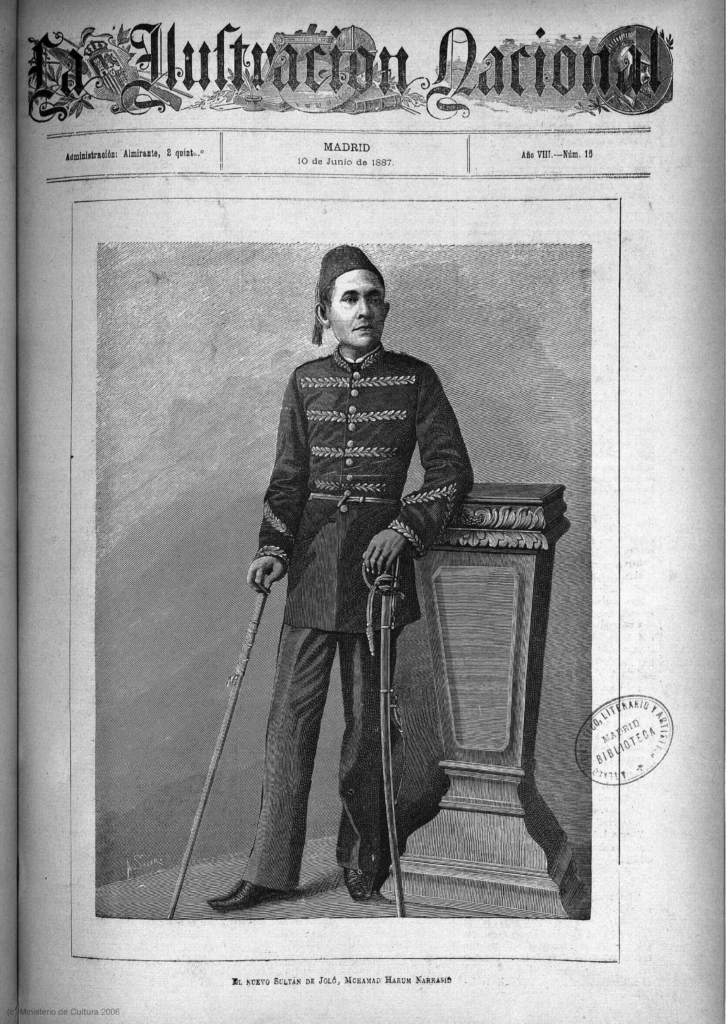

The barong under study, also known as ‘barung’, is a short, broad-bladed knife, considered the national weapon of the Tausug, an ethnolinguistic group on the island of Sulu. The knife is labelled as belonging to one of the three Juramentados who attacked the house of Sultan Harun on 16 August 1888, killing one Moro and three Chinese, also wounding seven Chinese. Sultan Harun, known as Muhamad Harun ar-Rashid, was the Sultan of Sulu appointed by the Governor-General of the Philippines, Emilio Terrero, from September 1886 until his abdication in 1893. Harun’s imposition provoked a war with the sultanate that caused heavy losses to the Suluans. Harun abdicated in 1893, and Amirol Quiram, the legitimate heir, was finally proclaimed Sultan of the archipelago. Born on the island of Palawan in the first half of the 19th century, Harun had been one of the datus of Palawan before becoming sultan and died in April 1899.

Pedro Ortuoste García, born in Manila in 1836, was a prominent translator of the Mindanao and Jolo languages for the Spanish administration in the Philippines. Ortuoste played a crucial role in military operations and in the translation of documents relevant to the colonial administration, participating in important events such as the signing of the sovereignty treaty in Jolo in 1878 and the appointment of Sultan Harun in 1886. Decorated for his dedication and bravery, Ortuoste was a central figure in the Spanish administration and in the understanding of the Mindanao and Sulu regions. During the 1882 crisis with Sultan Badaruddin II, he was considered for appointment as Secretary to the Sultan of Sulu.

In 1887, Ortuoste travelled to Madrid to attend the Philippines Exhibition and became friends with Víctor Balaguer. This materialized in several donations to the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB) from 1888 onwards. Although Ortuoste’s donations were significant, only five of the fifty-four objects mentioned in the museum’s bulletin are recorded as being donated by him. The coincidence of dates between the attack on Harun and the arrival of his donation in the port of Cadiz suggests that Sultan Harun’s knife was probably not part of this donation.

Even so, analysis of the documents and communications between Pedro Ortuoste and Víctor Balaguer reveals a complex network of donations and acquisitions related to Vilanova’s Philippine collection and allows us to make conjectures about the arrival and origin of certain objects. Ortuoste’s correspondence with Balaguer indicates that they had plans—through Alfredo Darnell, an important military officer based in Jolo—to send several objects, including a lantaka and the throne of the Sultan of Jolo.

The publication in the Butlletí de la BMVB confirms the receipt of the lantaka and the intention to send the throne once it had been restored, although the throne in question never reached Vilanova because of Ortuoste’s death. The lack of specific documentation on the barong, a weapon with a significant historical background, suggests that it may have been included in Darnell’s shipment, especially considering the coincidence with the attempt on Sultan Harun’s life. The absence of any mention in official archives and bibliography hints that information about the barong may have been treated with discretion due to its political nature and its potential impact on public perception and international relations.

Ortuoste’s death in May 1889 and the subsequent mention of this fact in the bulletin reflects the value of his contribution to the BMVB collection, while highlighting the difficulty of verifying all aspects of the donations. The conjectures about the barong and other artefacts highlight the need for further research to clarify the provenance and fate of these items. This illustrates how the lack of documentation can lead to almost detective-like speculation based on fragments of available information that we have managed to locate during the research process.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The barong under study (also written as ‘barung’) is a knife-shaped weapon consisting of a short, broad, single-cut blade, considered to be the national weapon of the Tausug, one of the ethnolinguistic groups of the island of Sulu. The length of the barong blade ranges from 20 to 56 centimetres, and in this particular case it is 36 cm. The most interesting thing about the barong is the accompanying label, which reads:

‘This belonged to one of the three Juramentados who broke into Sultan Harun’s house (16 August 1888). They killed one Moro and three Chinese, also wounding seven Chinese’.

Sultan Harun was named Muhamad Harun ar-Rashid and was appointed Sultan of Sulu (‘Jolo’ at the time of the Spanish occupation) by Philippine Governor-General Emilio Terrero in September 1886. He held this position until 1893, when he abdicated. Harun was born in the mid-19th century on the island of Palawan (also known as ‘Paragua’ during the Spanish colonial period), of which he was a datu (leader below the sultan). He died in April 1899.

To understand the figure of Sultan Harun, we have to go back to 1877, when Colonel Carlos Martínez became the second military-political governor of the archipelago. Thanks to his sagacity, this commander managed to re-establish order and peace and negotiate a sovereignty treaty with Sultan Jamalul Aʿlam (also known by the Spanish as ‘Diamarol’), which was signed in July 1878. Much of the credit for the success of the negotiations belongs to Datu Harun, who spared no effort to convince the sultan that peace and loyalty to Spain were preferable to a condition of continued hostility that could have detrimental consequences for the Sulu state. The treaty emphasized Sulu’s submission to Spanish sovereignty, and the terms of the Sulu text expressed this clearly. As the last treaty signed by the two states, it can be seen as defining the last stage of the relationship that existed between them and the exact position that Sulu occupied in the Philippine archipelago during the last period of Spanish rule.

Jamalul Aʿlam’s successor, the young Sultan Badaruddin II, was rather lax in the face of the rebelliousness of some datus of the archipelago who responded to Spanish attempts to consolidate their presence in the islands with a new wave of attacks by Juramentados. The Juramentados were Muslim warriors who—under oath and with the promise of being rewarded with Muslim paradise after their death—carried out suicide attacks with the aim of causing as many casualties as possible. According to Spanish chronicles, the Sultan was reluctant to follow the advice that the Philippine Government tried to impose on him through characters such as the translator Pedro Ortuoste and did not act as a guarantor of the stability acquired after the peace treaty. Badaruddin II was described as evasive, influenced by foreign powers, with a personality full of excesses and, on top of that, addicted to opium. His court was also frowned upon, especially his secretary, Hajee Omar, a man described as corrupt, who had a cordial relationship with the British of the Borneo Company. The same was not true of his mother, Inchi Jamila (Diamarol’s widow), who was de facto the most respected personality in the sultanate by the Spanish.

In 1882, the government of the Philippines, commanded at the time by General Primo de Rivera, discovered that Badaruddin had bought 200 rifles from the British. This event placed the Sultan in the spotlight, since, according to the Spaniards, he had clearly violated article six of Treaty 77, article 10 (AHN, Overseas, 5333, exp. 1, 1883). On his return from his pilgrimage to Mecca, the sultan was detained in Singapore by the Spanish consul, who tried to get him to travel to Manila to meet with the colonial authorities. The Spanish wanted to prevent Badaruddin from finalizing the purchase of arms from the British and to remove him as sultan. But the efforts of the sultan and his mother—who had great influence and better dealings with the Manila government than her son—managed to prevent this. Moreover, during these negotiations, the sultan’s son died, allowing him to again avoid the trip to Manila. The last news about Badaruddin tells us that he was unable to meet Governor Jovellar in Jolo in January 1884 because he was ill: ‘in bed, unconscious, [for] four days’ (Cirugeda, 06/03/1884). Shortly afterwards, on 21 February 1884, Badaruddin died of unknown causes.

The late sultan’s mother, Inchi Jamila, passed on the news of his death in a letter addressed to Alejo Álvarez, translator and companion of Pedro Ortuoste. In this letter, Inchi Jamila informed that the paduca Majazari Maulana, Sultan Muhamad, Amirol Quiram—the younger brother of the deceased—had been chosen as successor by both the datus and the cherifes. However, the council of elders (Rum-Buchara) had split into two factions: one in favour of Amirol Quiram—the legitimate son of Diamarol—and the other in favour of his uncle Aliubdin—the brother of the former sultan.

Aliubdin was a datu with affection for the Spanish regime, as he demonstrated when he presented his credentials to the Governor-General of the Philippines Joaquín Jovellar (Primo de Rivera’s successor), to whom he gave his own kris as a sign of respect. Also known to the Spanish as datu Zumbin, he ruled over Parang, Looc, Ygasang, and Paticolo (AHN, 5333/1, document, no. 46, 1884). Aliubdin had been residing in the village of Matanda since January 1884—‘a marallao, marallao, as they say, which in our language means good in superlative degree, that is, addicted to the Christian castila’ (Cirugeda, Gaceta Universal, 1884). The main buildings here (the datu’s house and the defensive blockhouse) were built from scratch by a detachment of twenty-five disciplinary workers provided by Colonel Parrado. The Spanish pavilion was erected in Matanda and Aliubdin was presented to the press at the time as a sympathetic and submissive character. At the beginning of March 1884, his followers gathered with the intention of proclaiming him sultan. The military-political government of Jolo then decided to send a delegation with Captains Darnell and Zamora and the interpreter Cipriano Enrile to dissuade Aliubdin’s supporters (Montero, II, 1888: 644). Despite attempts at negotiation, the supporters insisted on his proclamation. The delegation urged Aliubdin and his acolytes not to do so in Matanda, because it was a village built by the Spaniards and this might arouse the suspicions of the other candidate and his followers who were in Maimbung, the capital of the sultanate. On the night of 13 March, Aliubdin, his family and all those gathered moved to Patikul (‘Paticolo’ during the Spanish period) where he was proclaimed Sultan, according to the report sent to the governor. From then on, there was the unusual circumstance of two sultans in Sulu.

Despite the lack of agreement between the two factions, the situation became somewhat favourable to the Spanish occupation, as both sultans and their respective followers showed a cordial and peaceful attitude with the aim of gaining the favour of the colonial government. Jovellar maintained a status of neutrality with both sides and tried to mediate between them. In this sense, Pedro Ortuoste was sent with the proposal that the definitive election as sultan should go to Amirol Quiram and that Aliubdin should be in charge of the regency, which he could exercise individually or in the company of the widowed female Sultan. Despite Ortuoste’s mastery and knowledge of the Muslim languages and cultures of Mindanao and Sulu, he was unable to get both sides to accept this proposal.

In November 1884, Harun was sent by the Spanish to Jolo to mediate between the two sultans, to whom he was related. Harun was also the only surviving signatory of the 1878 treaty. Some chronicles of the time (Montero, II, 1888: 650) defend the thesis that—either because of the division between the sultans or because of the influence of the island’s governor, González Parrado—Harun conceived the possibility of becoming the new sultan himself. This may have been the reason for his trip to Manila in January 1885. There he was received by Jovellar, who claimed to defend the candidate of the Council of Elder’s choice, whoever he might be, thus maintaining his position of neutrality.

On 12 February 1885, General Terrero y Perinat was appointed Governor-General of the Philippines by Cánovas del Castillo. He took up his post on 4 April, bringing with him express orders from the Madrid government to expand Spain’s zone of influence in the Pacific, in imitation of what other nations such as Germany and the United States were doing—which sought to exert their influence, if necessary by force, to take over the area. It is striking that Terrero’s first trip, only five days after his arrival, was to Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan (Montero, 1888). On the latter island, he would meet the Datu Harun and talk to him not only about the future of Palawan, but also that of Sulu. Throughout the conflict, Pedro Ortuoste, translator and confidant of the governor general’s office, carried out missions of all kinds to Sulu and Mindanao, advising both Terrero and Harun himself.

On 31 August 1886, Ortuoste arrived in Manila with Harun—still the datu of Palawan—Hajee Omar—the secretary of the Sulu Sultanate—and the pandita Mustafa—the highest religious authority in the Sulu Sultanate. They were accompanied by 12 servants carrying a large amount of luggage, weapons, and even goats. The press at the time reported Harun’s arrival in Manila, but without realizing that Hajee Omar and the pandita Mustafa were not members of his court. During his stay in Manila, Harun was accompanied at all times by Pedro Ortuoste, who, predictably, acted not only as translator but also as advisor.

On 24 September 1886, at Malacañang Palace, the Governor-General began the ceremony by reading the telegram from His Majesty’s Government of Spain authorizing the appointment of Datu Harun as Sultan of Jolo. Immediately afterwards, he assigned him the title of Paduca Mahassari Maulana Amir Al-Muminin Sultan Muhamad Harun Narrasid. Following this, Harun took the oath of office on the Qur’an and ended the ceremony by saying: ‘I swear to uphold the capitulations and commands of His Majesty the King (of Spain)’. As the closing act of the appointment, General Terrero presented the new Sultan with an ivory and gold baton of command. Harun was the first Sultan of Sulu to be appointed as Amir Al-Muminin, forcing the members of the sultanate (Council of Elders, Datus and panditas) to consider him caliph. This would involve an element of friction with many of these members, as they did not accept this title and some even formally rejected it in writing to the Government in Manila (Donoso, 2023: 128).

While Terrero’s new belligerent policy was beginning to materialize in Manila, in Sulu, Amirol Quiram’s supporters were growing. On 6 October 1886, the new Sultan Harun, accompanied by Pedro Ortuoste, left Manila for Zamboanga on the mail steamer Francisco Reyes. Once in Sulu—and despite the cordial reception prepared with full honours by the military-political government of the island—the Sultan was forced to reside under the protection of the Spanish garrison in the face of overt hostilities from the Suluans. The main datus did not recognize him, and Inchi Jamila, widow of Diamarol and mother of Amirol Quiram, protested the illegality of the appointment to the Spanish governor of Jolo, Juan Arolas. Inchi Jamila was accompanied by her entourage, which included the sultanate’s minister of war, as well as the panglimas, a host of datus and men-at-arms. Even so, Harun’s appointment, approved by the King of Spain, was final. In case of resistance, Arolas had been ordered to provide military support to the new sultan.

A few days later, the governor of Jolo embarked Sultan Harun on the gunboat Panay with some 200 men of the garrison, some chiefs, and his interpreter, bound for Parang, where he was presented for the first time outside the Spanish stronghold that was the city of Jolo. The presentation was followed by recognition by the inhabitants of Parang, although this was not to last long. On the retinue’s return to Jolo, Parang was attacked by the followers of Amirol Quiram.

From then on, a military strategy of submission through warfare was implemented, consisting of punitive operations aimed at reducing the rebel forts (cottas) and subjecting their survivors to the new sultan. Attacks usually combined the use of heavy weapons with infantry and sometimes cavalry. The rebel cotta was bombarded until pathways were opened into the fort, where the infantry fought the occupants hand-to-hand until they were reduced. Once taken, weapons were requisitioned, valuables looted, and the remains of the fort burned. These operations were also combined with maritime expeditions to attack the rebels. In all cases, the survivors were forced to submit to the new sultan. For their part, those rebel datus who managed to escape erected new cottas to resist the attacks and organized suicide actions by Juramentados.

Over the next few months, military operations followed one after another and tension mounted throughout the island until, in February 1887, the Governor-General was forced to declare a state of war. At midnight on 10 February, a few days after the declaration, some 300 Sulu warriors appeared before the fort at Siassi, firing their rifles and lantakas. The garrison—despite suffering heavy losses—managed to repulse them after seven hours of crossfire, with slight intervals. From then on, Siassi saw daily combat. In March, Arolas asked Terrero for reinforcements, requesting the return of the Sulu troops that had been sent to the ongoing military operation in Mindanao. On 11 March 1887, Arolas received more than 350 troops, including regimental companies and disciplinary sections. Pedro Ortuoste accompanied the brigadiers in command of these reinforcements. On 14 April, two gunboats, a ship, and a schooner arrived at the port of Jolo.

Once these reinforcements arrived, a plan was put in place to destroy the opposition to the new sultan. The decision was made to attack Maimbung—where Amirol Quiram and his court lived—and the districts of the archipelago ruled by the Panglimas.

The name panglima originates from the Malay Islamic kingdoms, and its etymological root is the number five in Malay. This is due to the belief that Allah has a preference for odd numbers. Historically, a sultan or raja divided his territory into five districts, each governed by a panglima. The panglimas were responsible for collecting tribute, settling disputes, maintaining order, and spreading the Islamic faith. Chosen for their honesty, wisdom, and leadership skills, the panglimas were essential to the functioning of the sultanates and rajhanates and acted as intermediaries between the vassals and the king. According to Spanish Army reports, there were only four panglimas in Jolo (AGMM, 5460.14, 1887: 11).

As part of the plan of attack, the Spanish spread rumours that an expedition was being prepared against the island of Tapul, but on the night of 15 April, the gates of the Jolo square were opened and the Spanish Governor Arolas gave the order to advance towards Maimbung by land. A garrison of 800 men was ready to take the residence of the Sultan of Sulu by force. Maimbung had become the seat of the sultanate in 1876 and enjoyed a great deal of independence from the colonial government thanks to the trade that Chinese merchants maintained with Borneo and Singapore, which allowed them to obtain everything they needed without relying on the Spanish. For the colonizers, Maimbung was also a hotbed of piracy and smuggling of arms and ammunition that had to be eliminated. The day after the garrison left, it was the turn of the warships. Sultan Harun and fifty of his warriors, accompanied by Pedro Ortuoste, were part of the expedition.

The attack on the Maimbung fortification was imminent. From gun battles, the fighting shifted to hand-to-hand combat, which resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. In the end, the cotta was left strewn with corpses and in the hands of the Spanish army, which seized the loser’s supplies and weapons. According to the chronicles, Amirol Quiram managed to escape in the arms of his panditas (Montero, II, 1888: 713). In the throne room of the palace-house, some of the sultan’s belongings were found, such as his parasol, for example, a box of buyo or an armchair given by the English some time before. The house of Amirol’s mother, who was not there on the day of the attack, was occupied by the Spaniards. Subsequently, despite the inhabitant’s attempts at resistance, the entire village was forcibly reduced. The Chinese traders and their belongings were respected because they were considered neutral. They were, however, transferred to Jolo in order to supply the new sultan and contribute to the enrichment of trade in the Spanish-occupied area. On the side of Amirol’s followers, there were 131 dead—83 of whom were killed during the attack on the fort—although the figures vary depending on the source. The Jesuits, for example, increase this figure to 250 dead on the Sulu side (Albi, 2022: 547). Among the fallen were many of the Sultan’s court officials: from the governor of Maimbung to the Minister of War, panditas (religious leaders), secretaries, cherifes, datus, and majordomos. The day after the conquest of Maimbung, Sultan Harun landed with his warriors and had the dubious honour of setting fire to the remains of the fortification and reducing to ashes the former court of the sultanate and holy city, which he was now erasing through the colonizing force that supported his reign.

After the capture of Maimbung, between 8 and 9 May, the cotta of the Alimarang panglima in Damang was surrounded. The panglima agreed to submit to Sultan Harun on condition that it was with a solemn act in his house and in the presence of his followers. The next expedition headed for Patikul, but the army was ambushed, causing heavy casualties and forcing the Spaniards to make a forced retreat. For Arolas, such a setback called for a forceful response.

The next expedition, with the cooperation of the navy, set out for the island of Tapul with the aim of wiping out the Sayari panglima, who were also opposed to the imposition of Harun as sultan. On 24 May 1887, not without great difficulty, his cotta—a fort four times the size of Maimbung and about which the Spanish had no information—was destroyed. The panglima Sayari, dressed in red and wielding his kampilan, fought fiercely to the death along with eighty of his most loyal acolytes. In this operation, the Spaniards seized all the heavy weaponry, as well as arms and other objects, before reducing the cotta to ashes. While this was going on, Sultan Harun attacked the smaller cottas on the rest of the island of Tapul. The next day, the surviving Tapul datus and Sayari followers pledged their allegiance to Harun.

At the Philippines Exhibition in 1887, two exhibitors displayed weaponry requisitioned in the military operations at Maimbung and Tapul. On the one hand, Emilio Terrero himself, Governor-General of the Philippines, displayed arms and military material from the capture of Maimbung in the Additional section. In the same section, the Museo de Artillería displayed military matériel requisitioned in the operation against the Sayari panglima in Tapul.

During the following months, the subjugation operations continued: on 27 June, the peaceful surrender of the panglima Jaujari, who commanded six hundred warriors, was obtained (La Oceanía Española, 08/07/1887, no. 153: 3); and, on 19 July, Terrero informed Víctor Balaguer that Amirol Quiram, his mother Inchi Jamila and his uncle Aliubdin had submitted to the new Sultan Harun. Looc was conquered in August and in September the island of Pata, led by the panglima Sackilan. In the latter operation, Harun had a force of over a thousand men, thanks to the help of new datus, a panglima and twenty-four nobles that were accompanied by their vintas and warriors. In early 1888, other rebel cottas fell, such as Patikul, which at that time was led by the datu Calvi, still a follower of Aliubdin. By March, the fighting intensified.

In a letter from Terrero to Balaguer dated 3 June 1887, the Governor-General of the Philippines reported that ‘Harun continues to observe the same discreet conduct as before and I believe that he will soon be able to establish himself in the place he has chosen for his residence, which is certainly very suitable because of its situation and because it is close to the Plaza’. However, Harun himself had written to Terrero to inform him of the delicate financial situation he had been suffering since his arrival in Jolo, where he had incurred expenses of over four thousand pesos. As a collaborationist datu on the island of Palawan, Harun had received a salary of 900 pesos a year since the signing of the 1878 sovereignty capitulations. With his appointment as Sultan, the figure paid by the Philippine Government General increased to fifteen hundred pesos each year, but this was not enough for the Sultan who, in addition, since Diamarol’s death, had stopped receiving the five thousand pesos a year rent for North Borneo paid to him by Alfred Dent and Baron von Overbeck. Harun asked Terrero for help in settling the English debt, but Spain, which had not been a party to the lease, did not support him. Instead, the Spanish were obliged to defend Harun’s right to grant navigation licences to English ships wishing to enter Palawan waters. A function that Harun continued to perform from Jolo and which led to diplomatic conflict with the British, who protested that they had to travel to obtain such permits.

In his communications with Balaguer, Terrero describes the figure of the Sultan with paternalism and condescension. This was not the case with the superior of the Jesuit Mission in the Philippines, Pablo Pastells, who was very critical of the ‘abnormal appointment of Harun’, whom he called ‘the collection agent of the former Rajah Muda’. Pastells defined Harun’s court as a ‘hierarchical crowd of cherifes, panditas, imams and other Malays, with their turbans, from Singapore and other parts of India’ and warned that the imposition of the new sultan would make the ‘Morisma’ (moors) more resistant than ever to Christianity (Albi, 2022: 541). Even so, one of the episodes that contributed to this rejection was precisely the Jesuit missionary priest in the city of Jolo, who, in December 1886, baptized without consent a dying companion of Harun (BMVB, Terrero, Letter to Víctor Balaguer, 31/12/1886: 68). This led to the withering expulsion of the missionary, requested by Governor-General Terrero himself.

Since Harun’s arrival in Jolo, the city was heavily defended. After almost a year and a half of relative calm, in June 1888, a Juramentados attack shook the city of Jolo (La Oceania Española, 04/07/1888, no. 152: 3). The next attack of which we have found information is already that of the barong which is the subject of this report, the label of which reads: ‘This belonged to one of the three Juramentados who broke into Sultan Harun’s house (16 August 1888). They killed one Moro and three Chinese, also wounding seven Chinese’. We do not know whether the Sultan was present in the house, nor do we know what happened to the three Juramentados, who were most likely reduced or killed. Presumably, the Moro and the three Chinese were part of Harun’s court staff. It is also quite possible that the event was never made public, as it called into question Harun’s power and could have encouraged a new rebellion by the already subdued datus. The motive for the attack seems clear, Harun being the main collaborator of the colonizing power. We do not know whether it was because of this attack or not, but on 12 December of the same year, the Spaniards handed over to Harun a property that included a new palace in the town of Mubu (Donoso, 2023: 127).

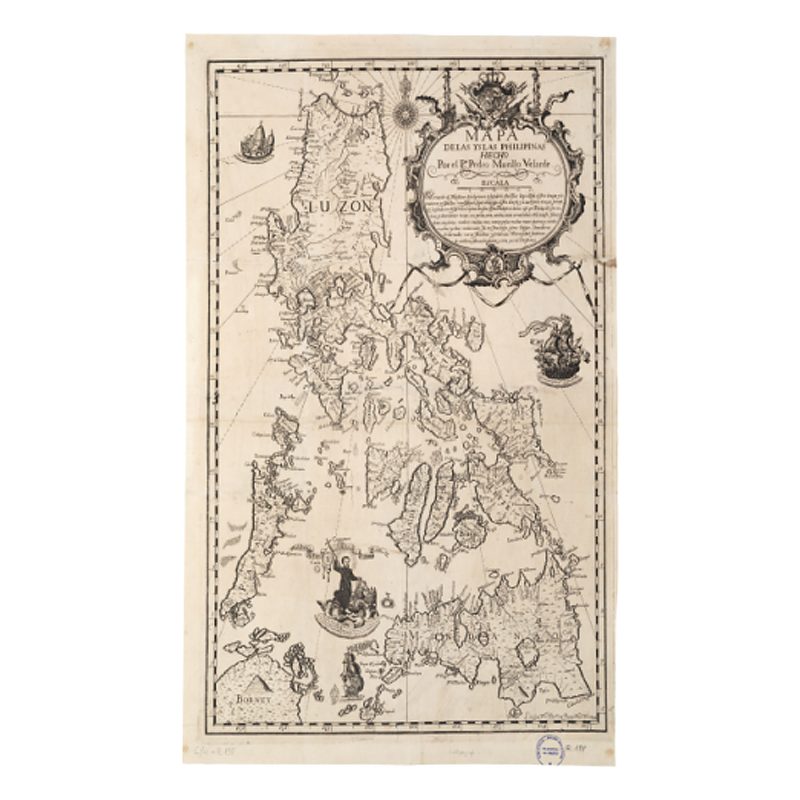

The question that immediately arises is: How did this weapon get to the BMVB? Although the monthly bulletin of the institution lists the names of the donors and the objects given, there is no trace of a donor and no entry for an object similar to the barong. As can be seen, the information available in the inventory on the barong is not entirely reliable, since the dating is contradictory (1899 on the one hand and 1887 on the other) and does not match the information available on its label. It is clear that the organization of the Philippines Exhibition, directed by Víctor Balaguer himself—as Minister of Overseas—was an opportunity to increase the Philippine collection, both with objects for the museum and with books for the library. Balaguer’s correspondence with Joan Oliva indicates that duplicates of works (where possible) were requested directly from the Philippines, as happened with the ethnographic map of Mindanao made by the Jesuits for the Madrid exhibition, which was sent directly from the Philippines to Vilanova before the opening of the exhibition (Oliva, 1887: 1). Similarly, both in Balaguer’s personal correspondence and in the bulletin itself, it is made explicit that, at the end of the exhibition, objects would be sent to Vilanova. At the very least, there was an article in the rules of the organization of the exhibition which stipulated that if, after the exhibition closed, any objects remained unclaimed, they would be given to charity (Philippines Exhibition, 1887). It was also foreseen that a large part of the objects would be given to the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar in Madrid.

The Madrid exhibition opened in June 1887, and in the Butlletí de la BMVB of July of the same year (1st period, no. 34, 6/7/1887: 5), we read:

‘We have learned from reliable sources that many of the objects in the exhibition of Filipino products, currently open in Madrid, will be ceded by their owners to this Institution, as a token of deference and gratitude to the founder of the museum library, now Minister of Overseas, to whom the realization of such an important event is due’.

In fact, Balaguer managed to get some exhibitors to donate their works directly to the BMVB and their donations were published in the bulletin from August 1887 to February 1888, the date of the last incorporation of objects from the Madrid exhibition. However, thanks to current provenance studies, it has been possible to identify objects from the Madrid exhibition that were not published in the bulletin. These pieces—the helmet of the datu Aliubdin (see report BMVB03), a coat of mail from the capture of Tapul (see report BMVB12), the barong from the attack on Harun—raise new questions: was it Balaguer who was interested in these objects, did they arrive at Vilanova by chance, or did Balaguer receive instructions from someone to prevent them from ending up in the Museo de Ultramar in Madrid?

In the course of the current research process, a figure has emerged who could provide new information on the subject or, perhaps, raise new questions. The individual in question is Pedro Ortuoste García, translator of the Mindanao and Jolo languages for the Philippine government administration. Born in Manila in 1836—the son of a Basque official in the accountant’s office of the Military Treasury, assigned to the Military Command of Polloc (Mindanao) at least since 1852—Ortuoste began his career as a translator when he was only nineteen years old. From 1858 to 1879, he served as a translator, participating in the military operations in Mindanao and Sulu. In 1879, he was appointed as an interpreter for the Joloan [sic] language for the Secretary of the Government General’s Office. Ortuoste was present at the signing of the Spanish sovereignty treaty in Jolo in 1878, as well as at the appointment of Sultan Harun in 1886.

Highly regarded by the Spanish army and administration, Ortuoste was decorated on numerous occasions for his involvement, courage, and bravery. Because of his knowledge of the languages of Mindanao and Sulu, he was a key figure for the Spanish administration both on the ground—during the war operations—and in Manila—responsible for the translation of everything related to these islands. While the Governors of Sulu and Mindanao and the Governors-General of the Philippines came and went, Pedro Ortuoste was the person who guaranteed knowledge of the situation in the ‘Morismas’. During the 1882 crisis with Sultan Badaruddin II, commanders close to General Primo de Rivera even considered the possibility of making him the secretary to the Sultan of Sulu (AHN, ULTRAMAR, 5333, exp. 1, no. 41, 1882-1883).

Pedro Ortuoste attended the opening of the Philippines Exhibition in Madrid as part of the retinue of the Government of the Philippines. Occasionally, he also accompanied and translated for the representatives of Mindanao and Sulu who were part of the human zoo. In March 1887, Governor Terrero wrote to the Minister of Defence in Madrid, Manuel Cassola, indicating that Ortuoste would meet with him to update him on the situation in Mindanao and Sulu, ‘which he knows better than anyone else’ (General Military Archives of Madrid [AGMM], 5460.7, 1887: 3). It was during this trip to Madrid that Ortuoste met Víctor Balaguer, and they became friends. This is clear from the numerous press reports on the exhibition and from the familiarity with which Ortuoste addressed Balaguer in the letters he subsequently sent him from Manila. From 1888 onwards, this link materialized in a series of donations to the BMVB. In the institution’s bulletin of 26 August 1888, a large donation of objects is reported, consisting largely of arms from Mindanao and Jolo. However, of the fifty-four objects identified in the museum’s bulletin, only five are currently recorded in the inventory as a donation by Pedro Ortuoste. Initially, our suspicions led us to believe that Sultan Harun’s knife might have been part of this donation, but the date of the attack by the Juramentados (16 August 1888) is after the arrival of Ortuoste’s donation in the port of Cadiz (13 August 1888), which leads us to rule out that it was sent by him at that time.

Some time later, a letter from Ortuoste dated 9 November 1888 informs Balaguer about sending new objects to Vilanova. Specifically, Ortuoste speaks of a lantaka that he wants to send through his friend Alfredo Darnell, an infantry captain in Jolo and one of the soldiers sent to Matanda to parley with Aliubdin when he wanted to proclaim himself sultan. In the same letter, Ortuoste explains that: ‘I have others ordered which I will send to you when I receive them, as well as other objects from those regions’. He also tells Balaguer that he has obtained the throne of the Sultan of Jolo—the cushions of which he has sent to be restored in China—and that it is destined for the museum in Vilanova. Finally, in May 1889, the Butlletí de la BMVB published the incorporation of the lantaka into the Philippine collection. The same publication announced that Ortuoste had obtained the throne of the Sultan of Jolo and that he would send it to Vilanova once its restoration had been completed. It is interesting that the throne is mentioned again, half a year after the first news in Ortuoste’s letter. These clues lead us to conjecture that there is a remote possibility that Darnell did indeed take the lantaka and new news of the throne to Vilanova as Ortuoste had announced. As the bulletin was published at the end of the month, it is possible that the lantaka arrived between the end of April and the publication of the May bulletin (as usually happened with all published donations).

On this occasion, the bulletin does not detail how the lantaka arrived, but simply that it was donated by Ortuoste. The fact remains, however, that from November 1888, when Ortuoste informs of the delivery to be made by Darnell, until the publication of the lantaka’s entry into the BMVB fund, almost seven months have passed. This is why, perhaps, the public announcement in the bulletin may correspond to a first-hand update, rather than a letter received months earlier. Could Darnell also have taken the barong of Harun’s attack? The fact that the attack does not appear in the documentation available in the AHN, in the BMVB archive or in the other archives and bibliography consulted suggests that the barong was given the same reserved status. An attack on the Sultan’s house, in a city controlled by the Spanish and in a territory coveted by other European powers, could have been interpreted in many ways, and publicizing it could have had unforeseeable political consequences. Based on this thesis, Darnell would have been the best person to bring such an important object to Vilanova. On the other hand, it seems reasonable that Pedro Ortuoste was involved in the shipment of the barong, especially if we take into account his profile, his proximity to the sultan, his influence at court and his knowledge of Balaguer’s intention to expand Vilanova’s Philippine collection. Even so, Ortuoste died in Manila on 12 May, the victim of a serous stroke caused by acute pericarditis, and nothing more was heard of the sultan’s throne. In August 1889, the museum’s bulletin reported Ortuoste’s death, praising his contribution to the museum’s Philippine collection, ‘which is, in its kind, the best and most complete in Spain’. Despite these arguments, it must be remembered that all that is stated in this paragraph is conjecture, to fill in the gaps left by the reconstruction of the facts.

Finally, Harun survived the attack from the Juramentados and continued to serve as Sultan of Sulu until 1893, when he quietly abdicated to cede the throne to Amirol Quiram. He then settled in Bono-Bono in southern Palawan and was given authority to rule over the Muslim population in Balabac and other islands in southern Palawan, including the present-day municipalities of Brooke’s Point, Rizal, Quezon, and Española. After Harun’s death, his son, Datu Bataraza, took his father’s place until he was appointed deputy governor during the American occupation of the Philippines. With the arrival of the Americans, his power was strengthened, and his leadership extended territorially to the south. Harun’s descendants remained in Palawan institutions until the late 1970s.

Estimation of provenance

The barong, a short, broad knife, is the national weapon of the Sulu Tausug. This specific barong, with a 36 cm blade, belonged to one of the three Juramentados who attacked Sultan Harun on 16 August 1888, causing several deaths and injuries. Sultan Muhamad Harun ar-Rashid had been appointed by Governor-General Emilio Terrero and ruled Sulu from 1886 until his abdication in 1893. Born in Palawan and died in 1899, Harun was instrumental in signing the 1878 peace treaty that secured Sulu’s submission to Spanish sovereignty.

After the death of Sultan Jamalul Aʿlam, his successor Badaruddin II failed to maintain stability, leading to rebellions and attacks by Juramentados. In 1882, Badaruddin was accused of buying arms from the British in violation of a treaty with Spain. After his death in 1884, disputes arose over the throne and two candidates were proclaimed sultans at the same time. In 1886, Harun was appointed sultan by Terrero, which caused internal friction. However, Harun was supported militarily by the Spanish.

In October 1886, Harun arrived in Sulu accompanied by Pedro Ortuoste. The new sultan met with local resistance and had to reside under Spanish protection. Although he initially gained some support, this was short-lived and was soon attacked by Amirol Quiram’s supporters. In response, the Spanish carried out several military operations—including heavy fighting and the destruction of fortifications—in an attempt to subdue the rebels.

In February 1887, the Governor-General declared a state of war. The offensive against Maimbung, the Sultanate’s capital, resulted in the destruction of the city and the transfer of Chinese traders to Jolo to ensure their loyalty to Harun. After the capture of Maimbung, military operations continued on Tapul Island and in other areas, resulting in the surrender of the rebels.

Although Harun consolidated his power, he faced economic difficulties and diplomatic conflicts. In June 1888, there was a Juramentados attack on Jolo, and in August 1888, three Juramentados attempted to assassinate Harun. The possible Spanish response was to grant him a new residence in Mubu in December 1888.

The central question is how the weapon in question reached the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB). The Butlletí de la BMVB does not mention the donor or the entry of the object. The information in the inventory is contradictory and the piece appears dated in different years (1887 and 1899). The Philippines Exhibition in Madrid, organized by Víctor Balaguer, increased the museum’s Philippine collection. Balaguer requested duplicates of works from the Philippines, and at the end of the exhibition, a significant number of objects, both from recognized and anonymous donors, were sent to Vilanova.

Pedro Ortuoste García, a translator of Mindanao and Jolo languages, may have played a key role in this story. Ortuoste, present at the signing of the sovereignty treaty in Jolo and the appointment of Sultan Harun, also participated in the Philippines Exhibition in Madrid. There he met Balaguer, initiating a relationship that resulted in several donations to the BMVB. In 1888, Ortuoste announced the sending of objects to Vilanova, including a lantaka and the throne of the Sultan of Jolo. Although the donation of the lantaka was published in the May 1889 bulletin, the throne was no longer mentioned. Ortuoste died in May 1889, and the bulletin announced his death in August, noting his contribution to the Philippine collection.

Alfredo Darnell, an infantry captain in Jolo and a friend of Ortuoste’s, may also have been involved in the arrival of the piece at the BMVB. Ortuoste mentioned in a letter of November 1888 that Darnell would deliver the lantaka and other objects to Vilanova on his behalf. Although the donation of the lantaka was documented, the barong of the attack on Harun is not specifically mentioned in the documentation. It is possible that Darnell, given his proximity to the events and considering his trip to Spain, may also have transferred the barong, especially considering the importance of the object, the need for confidentiality and the political implications of the attack.

Harun survived the attack and ruled Sulu until 1893, when he abdicated in favour of Amirol Quiram. Harun settled in Palawan and ruled various parts of the archipelago until his death. His descendants continued in leadership roles in Palawan until the late 1970s, well into the 20th century.

In summary, the barong probably reached the BMVB through Pedro Ortuoste and Alfredo Darnell. However, definitive proof is lacking, and the gaps in its estimation of provenance, stemming from missing documentation in the consulted archives, require further clarification.

Possible alternative classifications

As a possible alternative classification, the biography of Sultan Harun presented in this card would have to be synthesized in order to contextualize the object. Although we do not yet know who the collector or donor may have been, several fields could be modified, as proposed below.

Method of acquisition: Weapon seized after neutralizing a suicide attack.

Place of acquisition: Jolo, Sulu Island, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines.

Place of production/origin: Sulu Island, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines.

Classification group: Tausug people, Sulu Island, Sulu Archipelago, Philippines.

Regarding the dating, it must be, at the very least, after the attack.

Complementary sources

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 41. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 43. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 46. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1874-1889) Expediente personal de Pedro Ortuoste. Signatura: Ultramar, 52223, exp. 43. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1886) Exposición general de las Islas Filipinas, 1887. Madrid: Impr. y fundición de Manuel Tello. Fons general, signatura: FP/1187. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

(1887) Concesión de recompensas a heridos y contusos en las operaciones sostenidas en Mindanao. Signatura 5460.7. Madrid: Archivo General Militar de Madrid [consulta: 19/03/2024].

Albi, J. (2022). Moros. España contra los piratas musulmanes de Filipinas (1574-1896). Madrid: Desperta Ferro.

Balaguer i Cirera, V. (1886-1888). Correspondencia reservada con el Gobernador general de Filipinas. Fons general, signatura 5 Ms. 113. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Víctor Balaguer (1a època, 26 de juliol de 1887), (34). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

Cirugeda, F. (16 de gener de 1884). Carta Filipina. Gaceta Universal. Any VII, (1.854), 06/03/1884.

Datu Press (5 d’abril de 2019). Panglima: The power of five. <https://datupress.com/2019/04/05/panglima-the-power-of-five/> [consulta: 27/06/2024].

Diario de Manila. Any XXVIII, (224) [consulta: 30/06/2024].

—(31 d’agost de 1886 ). Any XXXVIII, (199), [consulta: 20/06/2024].

—(7 d’octubre de 1886 ). Any XXXVIII, (230), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

—(15 de març de 1888). Any XL, (62), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

Donoso, I. (2023). Bichara: Moro Chanceries and Jawi Legacy in the Philippines. Palgrave Macmillan. <https://www.academia.edu/98163950/Bichara_Moro_Chanceries_and_Jawi_Legacy_in_the_Philippines> [consulta: 02/11/2024].

El comercio (3a època, 23 de febrer de 1887). Any XVII, (44), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

Espina, M. A. (1888). Apuntes para hacer un libro sobre Joló: Entresacados de lo escrito por Barrantes, Bernáldez, Escosura, Francia, Giraudier, González, Parrado, Pazos y otros varios. Manila: Imprenta y Litografía de M. Pérez, hijo.

Expedient 5460.14 (1887). Concesión de recompensas sumisión del panglima Alimaranang en Joló, pàgina 11. Archivo General Militar de Madrid, [consulta: 18/03/2024].

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas Madrid (1887). Catálogo de la Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid … el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

La Oceanía Española (4 de juliol de 1887). Any XII, (152), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

—(8 de juliol de 1887). Any XII, (153), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

Montero y Vidal, J. (1888). Historia de la piratería Malayo-mahometana en Mindanao, Joló y Borneo. Fons general, signatura SL 5725-5726. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Ortuoste, P. (09 de novembre de 1888). Carta manuscrita de Pedro Ortuoste a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura 8800937. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Saleeby, N. M. (1908). The History of Sulu. Filipines: Bureau of Printing.

—(2021). Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion. Txèquia: Good Press.

Sánchez Gómez, L. Á. (2003). Un imperio en la vitrina: El colonialismo español en el Pacífico y la Exposición de Filipinas de 1887. Madrid: CSIC Press.

Smith, E. D. (1908). Report on Sulu Moros: Study of the Sulu Moros of the Sulu Archipelago (report by a U.S. Army officer). Filipines.

Taviel de Andrade, E. (1887). Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid en 1887 (2 vol.). Madrid: Imprenta de Uliano Gómez y Pérez.