Summary of results

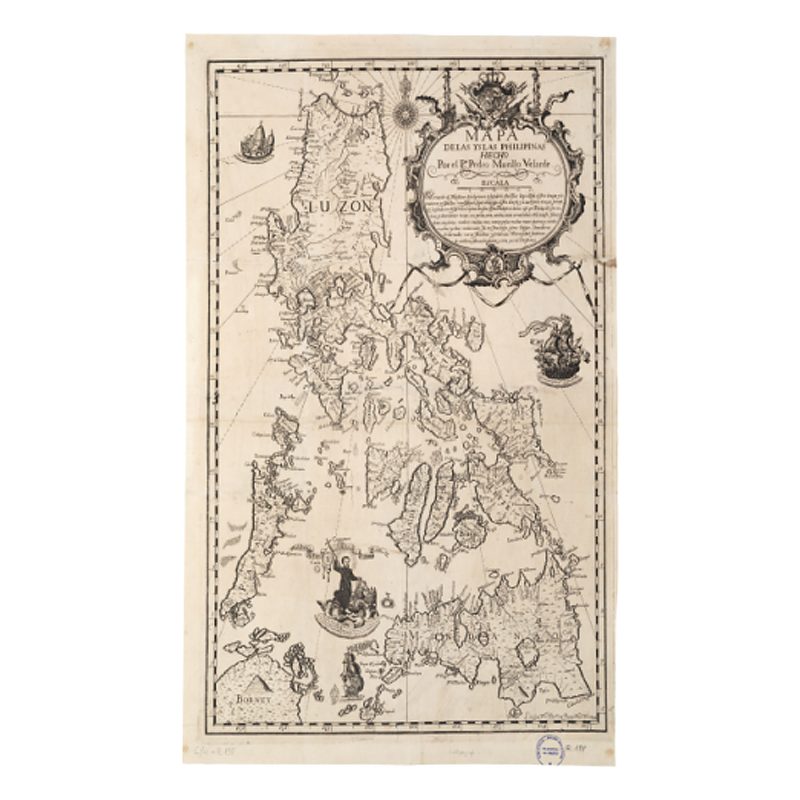

Prior to Spanish colonization, the island of Panay in the Philippines was inhabited by various indigenous groups, each with distinctive cultural and social characteristics. In the lowlands, the main groups were the Visayans, especially the Hiligaynon subgroup, who settled in the provinces of Iloilo and Càpiz. With an advanced social structure, the Hiligaynon lived in communities called barangays, led by datus or leaders. Their economy was based on agriculture, fishing, and interisland trade. Another significant group were the Karay-a, present mainly in Antique and some areas of Iloilo. Like the Hiligaynon, the Karay-a were organized in a system of datus and barangays, actively engaged in agriculture and trade. Meanwhile, in the highlands, groups such as the Suludnon maintained a more communal social structure and cultural practices rooted in oral traditions and animistic beliefs. The Ati, one of the oldest groups in Panay, inhabited mountainous and coastal areas and maintained a nomadic lifestyle centred on hunting and gathering.

Spanish colonization in the 16th century transformed the political and social landscape of Panay. With the arrival of the Spanish, evangelization became a key instrument for consolidating control over lowland ethnic groups such as the Hiligaynon and Karay-a, integrating them into the colonial religious and social structure. Religious orders, especially the Augustinians, played a crucial role in local administration, economic development, and education. In the 19th century, the expansion of sugar production and international trade fostered significant economic changes, especially in Iloilo, which became a sugar trading centre. The influence of Chinese mestizos, or Sangleys, on the economy was notable, both leading the textile industry and participating in the sugar business in Negros. Despite attempts at colonial integration, the region experienced resistance, as in the Antique rebellion of 1888, which reflected local discontent and the struggle for autonomy from Spanish rule. This rebellion, although suppressed, demonstrated the organizational capacity and resilience of local communities in their quest for self-determination.

In this context, in 1886, the Civil Guard Juan Díaz Peña seized, in the municipality of Capiz, a double-pointed spear during the arrest of Inocente Isarrán, a possible datu or rebel leader remontado (as those who sought refuge in the mountains to avoid colonial impositions were called). This spear, along with other weapons, was donated to the BMVB in 1890 by Patricio Montojo, a Spanish admiral who played a prominent role in Philippine naval history. In 1898, the Spanish squadron under his command was destroyed by the US fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay, which led to the capture of Manila and the loss of the Philippine archipelago from the Spanish. It is not known, however, how Montojo was able to acquire these weapons.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The present double-pointed spear is a rare object from the Philippine collection of the BMVB. As there is no information in the inventory of the collection, the Butlletí de la BMVB, published monthly during the first years of the institution’s existence, was consulted. The different donations of Filipino objects published in the bulletin and received between May 1885 and October 1901 were reviewed.

In December 1890 (Butlletí de la BMVB, 1890, n.º 75: 7), the following donation from Mr. Patricio Montojo was published:

‘This time he has sent us a rondache, two shields and four spears. The latter belonged to a gang of thugs from Copiz [sic], in the Philippine Islands, whose leader, called Inocente Isarran, was captured by the sergeant of the Civil Guard Juan Diez Peña in 1886. The sergeant was wounded with the longest spear, one guard with the medium one, and one guard was killed with the smaller one. The fourth spear is made out of two blades (we did not possess any of this kind) and is the weapon of the executor of the feudal justice munari. The rondache is typical of the indigenous infidels of the left shore of the Pulangui, Rio Grande, of Mindanao. As for the shields, they come from the Moros Illanos, untamed and fierce pirates who inhabit the Illana Bay of Mindanao’.

Patricio Javier Montojo y Pasarón (1839–1917) was a Spanish admiral who played a crucial role in the naval history of the Philippines. He began his career in the navy in 1852 and was noted for his participation in various missions and conflicts, especially in the Philippines. In 1861, Montojo was part of the naval expedition that took part in the assault and capture of the Pagalungan cotta (fort) in Mindanao. He was promoted to lieutenant of navy in 1862 for his participation in this action. He made numerous trips and missions in Southeast Asia, receiving a decoration for his participation in Franco-Spanish actions. In 1866, he was part of the Spanish squadron during the War of the Pacific, taking part in the blockade and bombardment of Callao. After various postings in Cuba, Puerto Rico and South America, he returned to the Philippines in 1887 and was commander of the Southern Division, in charge of naval surveillance in the Jolo archipelago, an area known for pirate activity. By 1896, he had been promoted to rear admiral and returned to the Philippines as Commanding General of the Philippine military port and squadron.

In 1897, during the armed uprising for independence in the archipelago, Montojo led naval operations in support of land forces, attempting to quell the rebellion in Cavite province. In 1898, the Spanish squadron under his command was destroyed by the American fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay, which led to the capture of Manila and Spain’s loss of the Philippine archipelago. Montojo was subsequently suspended from his duties and transferred to Madrid to face a Supreme Council of War and the Navy, which sentenced him to prison and disqualified him from active service.

Montojo was undoubtedly aware of Balaguer’s initiative to obtain donations for the BMVB, as attested to by two of his letters from Víctor Balaguer’s epistolary collection. The first, written from Cavite, reports a shipment of arrows (Montojo, 10/11/1887) and another refers to objects from Puerto Rico (Montojo, 13/09/1894), apart from the donation published in the bulletin which includes the present double-pointed spear, which became part of the Philippine collection at the end of 1890.

Returning to the description in the bulletin, it tells us that the four spears belonged to ‘a gang of thugs from Copiz, in the Philippine Islands, whose leader, called Inocente Isarran, was captured by the sergeant of the Civil Guard Juan Diez Peña in 1886. […] The fourth spear is made out of two blades (we did not possess any of this kind) and is the weapon of the executor of the feudal justice munari’.

As for the location, it is Capiz (Kapis in Tagalog) and not ‘Copiz’ as the text says. The region of Capiz, which is located on the island of Panay, has a significant mountainous area in the Sierra Madre mountain range, which extends across several provinces of the island. This mountainous area forms part of the topographical features that separate Capiz from other neighbouring provinces. The province was distinguished by its agricultural production, with rice and sugar as its main crops. These agricultural activities were facilitated by the presence of large fertile lowlands and a network of rivers that provided water for irrigation.

Society in Capiz during the 19th century was organized in a system of barangays, led by datus or local leaders, although the political and social structure was increasingly integrated into the Spanish colonial system. The influence of Catholic missionaries was notable, as they established churches and schools in the area that promoted conversion to Christianity and Western education. This process of evangelization had a profound impact on the local culture, integrating Catholic religious practices into the daily life of the inhabitants. But their exertion of a dominant role (appreciated by the government) and increasingly frequent abuses of authority would provoke tensions with the populations (Blanco, 2015: 33).

The Hiligaynon were the predominant ethnic group in the Capiz region. They are part of the Visayans and were known for their language, also called ‘Hiligaynon’ or ‘Ilonggo’. This group was mainly engaged in agriculture, fishing and interisland trade. In addition to the Hiligaynon, some Karay-a also lived in nearby areas, especially along the border with the province of Antique. Although the Karay-a were more predominant in Antique, there were significant cultural and commercial interactions between the Karay-a and the Hiligaynon in Capiz. The Ati, an Aeta indigenous group, also inhabited the region, although mostly in the more remote and mountainous areas. The Ati lived by hunting, gathering, and subsistence farming, and although their presence in Capiz was smaller compared to other groups, they maintained their ancestral cultural practices.

The bulletin states that the weapons were seized from a gang of thugs by Civil Guard sergeant Juan Díaz Peña. The Civil Guard in the Philippines played a crucial role in the Spanish colonial administration, acting as a key security force in maintaining public order and suppressing uprisings. It often faced challenges related to insurrection and mistrust of the local population, which complicated its task. Despite its efforts to implement an effective security system, internal dynamics and mistrust between European officers and local troops undermined its effectiveness. The Civil Guard consisted mainly of local personnel under the supervision of Spanish officers, which, while facilitating mobilization and knowledge of the terrain, also entailed problems of loyalty, as some local guards sympathized with the insurgents (Pezuela, 1877: 67). Spanish officers also abused their power and sometimes they would be corrupt or take advantage of their position to embezzle. In many parts of the archipelago, the Civil Guard was the only operational security force.

We have been able to find out little about Juan Díaz Peña. He was on active service from 1882 (General Military Archives of Madrid [AGMM], 1886, 5459.4: 8), and there are three documented operations in which he was involved.

In the Manila newspaper El Comercio of 18 February 1887, there is the description of two operations in which First Sergeant Juan Díaz Peña participated in the province of Capiz. One of them, which took place on 13 January 1887, in a place called Tinugean, was reportedly the result of an assault on a merchant and the butler of the rector of the town of Cariés in the district of La Concepción (Iloilo). They were attacked by a gang of thugs made up of eight men armed with bladed weapons and firearms. Juan Díaz commanded the pursuit operation in which—in addition to recovering part of the stolen objects—the leader of the gang, the ‘famous ringleader Julián (a) Pag-pag’ (El Comercio, 18/02/1887: 3), and five other members of the gang were arrested. The second operation—whose dossier has also been located in the AGMM (ibidem)—took place, in the Miauay mountains of the town of Ivisan, there, Sergeant Peña arrested a soldier with an unlimited licence who was manufacturing weapons in a clandestine smithy and supplying them to criminal groups.

On the other hand, there is one last documented operation, in April 1886, in which some holy men hiding in the mountains were arrested. This operation was aimed at breaking up a group of remontados and fanatics who were disturbing security and preventing the total assimilation of numerous mountain people (AGMM, 1886, 5459.4: 4).

The fact is that Spanish colonization introduced a new system of colonial labels that had a significant impact on the definition of the social identity of the inhabitants of Panay (German: 24). The terms used by the colonizers to describe indigenous groups often reflected colonial hierarchies and stereotypes that influenced how these groups were perceived both by the colonizers and among themselves. Such labels often simplified the island’s rich cultural diversity and promoted the idea that highlanders, such as the Suludnon and Ati, were less civilized than lowland groups, who were more easily integrated into the colonial system. On the other hand, not only criminals, but all those who did not accept Spanish rule, especially the leaders or chiefs, were considered evildoers. In the case of babailanes (indigenous religious leaders), considered holy men, healers, shamans or seers, they were considered superstitious and even heretical practitioners (Blanco, 2015: 18).

Considering these colonial labels, Juan Díaz Peña’s arrest of Inocente Isarrán and his gang of thugs takes on a different meaning. And the double-pointed spear, described as the ‘weapon of the enforcer of feudal munari justice’, plays a decisive role. The term ‘munari’ was used by the Spanish Army in Sulu and Mindanao to designate an Islamic judicial figure present in the Muslim sultanates of the southern islands (Espina, 1888: 579). In this context, the munari was a type of official or leader who exercised judicial functions, acting as a judge or arbitrator in civil disputes and legal matters within the community. The use of the term in the bulletin note may indicate that the person who wrote it was familiar with this term, most likely from having lived in these places. It is possible that Montojo himself provided such information, since he lived in both Mindanao and Jolo.

Even so, in Panay social structures, there was no such figure, but his functions rested with the local leaders or datus. The datus also acted as judges, settling local disputes based on traditional laws and customs. It is therefore difficult to believe that the leader of a gang of criminals was at the same time the administrator of feudal justice. It makes more sense to believe that Inocente Isarrán was a datu who rebelled against the Spanish administration of the Capiz area. He could be a remontado, as the Spanish called those who sought refuge in the mountains to avoid colonial impositions such as tribute, forced labour (polo y servicios) and religious conversion to Christianity. As they lived in hiding, they were considered to be criminals. As to which group they might have belonged to, they could have been Hiligaynon or Karay-a. These groups lived in the lower areas of Capiz and were more exposed to colonial domination for a longer time, as their Spanish name might indicate.

We have not been able to find any information on how Montojo was able to obtain this spear and send it to Vilanova.

Estimation of provenance

The double-pointed spear, a rare object from the Philippine collection of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB), came to Vilanova through a donation by Patricio Montojo. In the Butlletí de la BMVB of December 1890, it is mentioned that Montojo donated a series of objects, including this spear. Patricio Javier Montojo y Pasarón was a prominent Spanish admiral who played a crucial role in the naval history of the Philippines. His career began in 1852, and he participated in various missions in the Philippines and Southeast Asia, including military actions in Mindanao and engagements during the Pacific War. Montojo maintained a close relationship with Víctor Balaguer, as evidenced by his letters and donations of items to the BMVB, including weapons and other Philippine artefacts.

The lance was part of a set of weapons captured from ‘a gang of thugs’ in Capiz, Philippines, led by Inocente Isarrán. This group was disbanded in 1886 by Civil Guard sergeant Juan Díaz Peña, who confronted these bandits and captured the leader. According to the bulletin, the spears were used during the confrontation, causing injuries to some members of the Civil Guard. The double-pointed spear is described as the weapon of the ‘executor of feudal munari justice’, suggesting a symbolic or authoritative role in Isarran’s group.

The region of Capiz, on the island of Panay, was characterized by its mountainous geography and agricultural production. During the 19th century, society in Capiz was structured in barangays led by datus, with a strong influence of Spanish colonization and Catholic evangelization. The Hiligaynon, predominant in the region, along with some Karay-a and Ati, constituted the main ethnic groups. The context of Inocente Isarrán’s capture suggests that he may have been a datu or remontado rebel leader who resisted colonial impositions and possibly led a community opposed to Spanish administration. The double-bladed spear, considered a symbolic object of authority, reinforces this interpretation. However, no specific details have been found on how Montojo acquired the spear before it was sent to Vilanova.

Possible alternative classifications

Based on the findings of this investigation, the information in the BMVB inventory should be modified:

Method of acquisition: Confiscation.

Place of acquisition: Province of Capiz, Panay Island

Place of production/origin: Province of Capiz, Panay Island

Collector: Juan Díaz Peña

Donor or seller: Patricio Javier Montojo y Pasarón

Classification group: Hiligaynon or Karay-a groups, Province of Capiz, Panay Island

Date of acquisition by the institution: December 1890.

It would also be important to include information in the inventory on the historical contextualization of the object’s place of origin, as well as the possible cultural carriers of the object.

Complementary sources

Agoncillo, T. A. (1990). History of the Filipino People. Quezon [Filipines]: Garotech Pub.

Blanco Andrés, R. (2015). Los sucesos de Antique de 1888. <https://www.agustinosvalladolid.es/estudio/investigacion/archivoagustiniano/archivofondos/archivo2015/archivo_2015_01.pdf> [consulta: 05-07-2024].

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Víctor Balaguer (1a època, 1890), (75). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

Cabrero, L. (1990). La espiritualidad de la hueste de Legazpi: La conquista pacífica de las Islas Filipinas. <https://dadun.unav.edu/bitstream/10171/4768/1/LEONCIO%20CABRERO.pdf> [consulta: 05-07-2024].

Castellanos Escudier, A. (s. d.). Biografía de Patricio Javier Montojo y Pasarón. Real Academia de la Historia. <https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/13155/patricio-javier-montojo-y-pasaron> [consulta: 07-01-2024].

Elizalde, M. D., i Huetz de Lemps, X. (2015). Un singular modelo colonizador: El papel de las órdenes religiosas en la administración española de Filipinas, siglos XVI al XIX. Illes i Imperis, (17), 185-201. <https://www.raco.cat/index.php/IllesImperis/article/view/299480> [consulta: 05-07-2024].

Espina, M. A. (1888). Apuntes para hacer un libro sobre Joló: Entresacados de lo escrito por Barrantes, Bernáldez, Escosura, Francia, Giraudier, González, Parrado, Pazos y otros varios. Manila: Imprenta y Litografía de M. Pérez, hijo.

German, M. A. (s. d.). (Re)searching identity in the highlands of Central Panay. AghamTao, 19, 20-37. <https://pssc.org.ph/wp-content/pssc-archives/Aghamtao/2010/06_(Re)%20Searching%20Identity%20in%20the%20Highlands%20of%20Central%20Panay.pdf> [consulta: 05-07-2024].

McCoy, A. W. (2017). Formación de élites y revolución social en las Filipinas del siglo XIX: La sociedad de plantación de las Visayas Occidentales. Dins M. D. Elizalde i X. Huetz de Lemps (ed.), Filipinas, siglo XIX: Coexistencia e interacción en el Imperio español (p. 137-170). Madrid: Polifemo.

Ministerio de Guerra (1886). Concesión de recompensas a la Guardia Civil por capturar a varios malhechores en Ivisán (Filipinas). Fons secció d’Ultramar del Ministerio de Guerra, signatura 5460.5. Madrid: Archivo General Militar de Madrid.

—(1886). Petición de recompensas por la captura de unos santones en Cápiz (Filipinas). Fons secció d’Ultramar del Ministerio de Guerra, signatura 5459.4. Madrid: Archivo General Militar de Madrid.

Montojo, P. (10 de novembre de 1887). Carta manuscrita a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura 8701389. Vilanova i La Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Montojo, P. (13 de setembre de 1894). Carta manuscrita a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura 9400369. Vilanova i La Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Pezuela, J. F. de la (1877). España en Filipinas: Estudio de algunos problemas que ofrece la situación actual de las islas. Madrid: Imprenta de Manuel Tello.

Regalado, F. B. (juliol de 1966). The Story of Ancient Panay: Its Settlement and Pre-Spanish Culture. The Southeast Asia Quarterly, 75-87. <https://repository.cpu.edu.ph/bitstream/handle/20.500.12852/2695/05_SAQ_REGALADOFB_1966.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y> [consulta: 05-07-2024].

Saleeby, N. M. (1905). Studies in Moro history, law, and religion. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing. <https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/41770> [consulta: 05-07-2024].

Spanish Filipino Genealogy Research Services (28 de gener de 2015). Teniente coronel de la Guardia Civil en Filipinas [Fotografía]. Facebook. <https://www.facebook.com/661439860616685/photos/a.661442220616449/812576535503016/> [consulta: 21-09-2024].