Summary of results

The Macana of Ayonique, in the collection of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB), represents the complex colonial dynamics and challenges of Spanish occupation in the Philippines and other Pacific regions during the 19th century. This object is a kind of wooden mace with the inscription ‘Macana of Ayonique. Defence of the Indians’. Its exact context and provenance are not specifically documented in the museum’s inventories.

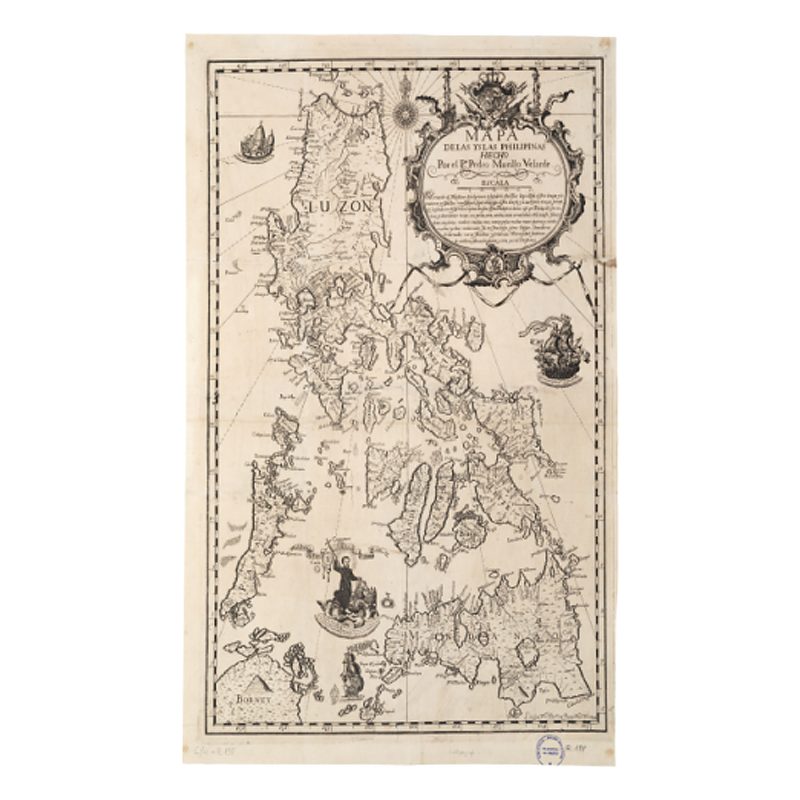

Despite more than two centuries of Spanish presence in the Philippines, by the late 19th century, several areas, including parts of Mindanao and the Cordillera Central of Luzon, remained outside the effective control of the colonizers. Geopolitical tensions and the perceived threat from other European powers, such as Germany and Britain, prompted Spain to reassert its dominance over these regions. This translated into colonial efforts such as the occupation of the Caroline Islands (now the Federated States of Micronesia), including the island of Yap, where this macana may have been picked up.

The Caroline Islands crisis of 1885 highlighted the fragility of Spanish sovereignty. International pressure and the diplomatic intervention of Pope Leo XIII were necessary to resolve a territorial dispute with Germany. Although Spain retained sovereignty over the islands, its administrative control remained limited. This period was marked by the traditional strategy of employing religious missionaries to establish administrative structures, an approach that faced significant local resistance.

The term ‘macana’, of Taino origin, was used to describe offensive weapons resembling truncheons or heavy clubs, commonly employed by Native Americans and, by extension, the term was also used in the Spanish colonies of the East Indies. Ayonique’s macana reflects the appropriation and reinterpretation of indigenous objects in the colonial context, where these artefacts were collected and exhibited as exotic curiosities.

The Philippines Exhibition in Madrid in 1887 was a key event for the integration and dissemination of colonial material in Spain. This exhibition displayed objects from the Philippines and other colonies, emphasizing a supposed cultural and administrative dominance. However, this exhibition also reflected a Eurocentric view that simplified and decontextualized indigenous cultures, presenting their peoples and artefacts as savages or primitive.

The Ayonique macana came to Vilanova from the Philippines Exhibition through the mediation of Víctor Balaguer, founder of the museum and a key figure in the organization of the exhibition. Balaguer ensured that many of the objects featured in the exhibition were donated to the BMVB, enriching the collection with artefacts that provide valuable testimony to colonial interaction.

Despite the lack of detailed documentation of its origin, the Ayonique macana evidences the complexity of colonial relationships and the continuing influence of these narratives on the representation and understanding of indigenous cultures in museum contexts. A decolonial approach involves acknowledging these dynamics and seeking ways to represent indigenous histories and cultures respectfully and accurately, challenging colonial simplifications and valuing local perspectives.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The object in question is a kind of one-piece wooden mace, with an inscription that reads ‘Macana of Ayonique. Defence of the Indians’. In the same BMVB inventory, the object is defined as rare, although there is no contextual information about it. The macana is an offensive weapon, similar to a machete or a mace, made of hard wood and sometimes with stone cuts, which was used by the Native Americans. The term ‘macana’, of Taino origin, is widely used to refer to the wooden maces used by warriors of the pre-Columbian peoples of Central and South America, although it is also often used to refer to heavy clubs. This term most likely became part of the armament vocabulary of the Spanish conquistadors in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and by extension was used in the same way in the Spanish East Indies. As for the place of origin, Juan Álvarez Guerra—politician, traveller, writer, and royal curator of the exhibition—in the first volume of his Viajes por Filipinas, entitled De Manila a Marianas, describes his journey to the island of Yap in the Caroline Islands archipelago:

‘We approached Ayonique, passed by the Duñgas reef, cautiously passed the Buncual cove and already had the mouth of Bahía de Agui in sight’ (Álvarez, 1887: 230).

Yap Island, in the west of the Caroline Islands (now the Federated States of Micronesia), was home to diverse ethnic groups with a common culture and unique particularities. The Yapese, the main group, were known for their hierarchical social structure and complex trade networks based on agriculture, fishing and maritime trade. Famous for their rai stones, used as currency, the Yapese maintained trade relations with nearby atolls such as Ulithi and Ngulu. The Spanish understood the Yapese through their Eurocentric prejudices, describing them as lightly built but classifying them in general terms as a ‘Malay race’. Local leaders were referred to as ‘caciques’ (meaning, chieftains) or ‘reyezuelos’ (literally, small-time kings) (Miguel, 1887: 70), minimizing the legitimacy of their authority. Yapese society was organized into clans and lineages, with a hereditary system determining the social hierarchy. Their cultural practices included ceremonies and dances, fundamental to their identity. Even so, the colonial approach simplified their social structure, referring to castes of free and enslaved people without recognizing the complex internal dynamics.

In order to try to reconstruct the arrival of this macana from the island of Yap at the BMVB, it is necessary to have a brief look at the figure of Víctor Balaguer, the founder of the museum. The Royal Academy of History (RAH) defines him as a politician, writer, journalist, historian and cultural patron. Although this approach is appropriate given his wide-ranging activity, it is perhaps arbitrary. Another outstanding facet of his character, his 33rd degree in Freemasonry, is not even mentioned. Also remarkable was his passion for the Philippine archipelago, which he himself explained in his book Islas Filipinas (Memoria), published in 1895 .

In 1884, using his library and personal collections as a starting point, he opened the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum in Vilanova i la Geltrú, an institution that served as a library, a newspaper library, a museum, and an educational centre. He also made substantial donations of books for the foundation of new libraries, such as the one in Sitges.

Balaguer, served a third term as Minister of Overseas (from 10 October 1886 to 14 June 1888), promoting important reforms in tariff policy, public works and transport, and communications. Balaguer also promoted the creation of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, in Madrid—which he directed until his death—and the Museo Biblioteca de Filipinas, in Manila. At the same time, Balaguer was the true architect of the organization of the Philippines Exhibition, held from 30 June to 30 October 1887, in the Retiro Park in Madrid.

Madrid’s Retiro Park was the venue for the exhibition. The Crystal Palace, also known at the time as the ‘Pabellón de Cristal’ (literally, Crystal Pavilion), was built for the exhibition. And although it was planned to be converted into the headquarters of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, this never happened.

The exhibition displayed a group of between forty and fifty people from the Philippines along with local objects, products, and plants, recreating the ‘natural habitat’ of the indigenous Filipinos in the palace lake. This was the first human zoo in Spain in modern times. Following its success in terms of attendance, there were private companies that organized new exhibitions of people from outside Europe, both from Spanish colonies and from other countries, a practice that existed until 1942.

For the collection of artefacts, a centralized agency was set up, based in Manila, with provincial and local branches. The local boards collected the artefacts on the ground and sent them to the provincial subcommissions, which in turn sent them to Manila, from where they travelled to the mainland on board the ships of the Compañía Transatlántica, owned by Antonio López y López. As Sánchez Gómez points out, the composition of this system of artefact collection reflected the social and administrative structure of Philippine society at the time (2003: 44): the local boards were composed of members of the indigenous elites, while the provincial and central commissions included members of the clergy as well as civil authorities.

In the Butlletí de la BMVB of July 1887, page 5, the big news is the inauguration of the exhibition by Víctor Balaguer, under the auspices of the Queen Regent. At the end of the article, there is a separate paragraph that reads:

‘We have learned from reliable sources that many of the objects in the exhibition of Filipino products, currently open in Madrid, will be ceded by their owners to this Institution, as a token of deference and gratitude to the founder of the museum library, now Minister of Overseas, to whom the realization of such an important event is due’.

Balaguer requested duplicates of works directly from the Philippines, such as the ethnographic map of Mindanao sent to Vilanova from there (Oliva, 1887: 1). Balaguer’s correspondence and the bulletin also mention the sending of objects to Vilanova after the exhibit. Donations from the exhibition were recorded between October 1887 and February 1888, although some objects do not appear in the museum’s publications. The monthly bulletin and the correspondence between Balaguer and Joan Oliva provide valuable information on the acquisitions and allow us to identify donors, questioning the BMVB’s inventories. The reliability of the inventories of the Philippine collection is questionable, since there are numerous dating, definition, and cataloguing errors. In the rules of the organization of the exhibition, there was an article in which it was stipulated that if, after the closing of the exhibition, any objects remained unclaimed, they would be given to charity.

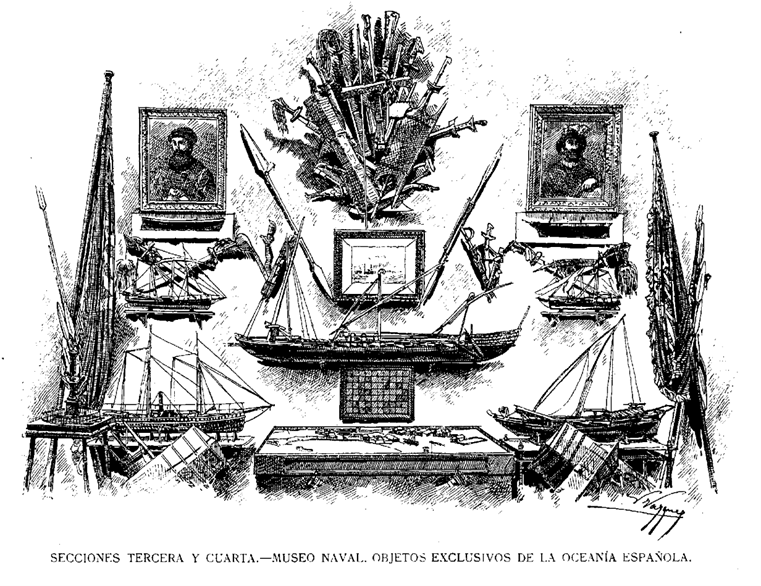

The Philippines Exhibition held in Madrid in 1887 had a notable impact on public perception and Spanish colonial policy. This exhibition not only served to communicate military successes in the Philippines, but also facilitated the integration and dissemination of exotic colonial material, such as weaponry and cultural artefacts, in a European context. So much so that objects from other Spanish colonies, not just the Philippines, were also displayed. The additional section of the exhibition featured two exhibitors who did so. On the one hand, the National Archaeological Museum presented a large collection of objects from the defunct Museo Ultramarino, mostly from the Philippines, although it also included objects from Puerto Rico (Catalogue: 636) and Fernando Poo (Catalogue: 642 and 644). On the other hand, the Museo de Artillería, among its extensive arms collections, presented numerous objects from the Caroline Islands, which were part of the Spanish East Indies.

Among the objects exhibited by the Museo de Artillería, in the blunt weapons section (Catalogue: 645), were two macanas from the Sandwich Islands, and another from the Caroline Islands. According to González Enríquez (1995: 94), there is a Carolinian macana in the Museum of the Americas, with other Carolinian objects, which came from the Scientific Commission attached to the military squadron destined for the Pacific (1862–1866). The provenance of these objects is diverse, but it is specifically mentioned that many of them come from the scientific-military expeditions organized from the Iberian Peninsula or from the American coasts during the 18th century. It also indicates that some of these pieces came to the museum through private collections such as the Borbón-Lorenzana or Rivadeneira, and others were acquired from the Philippines Exhibition of 1887. This information could confirm that the piece in Vilanova could be the Carolinian macana displayed at the exhibition: ‘It is made of hard wood, in one piece, with an ogival head and simply carved at the end’ (Catalogue: 646). As we have been able to ascertain during the research process, it is possible at least one other object from the BMVB (report BMVB_12) may have been part of the Museo de Artillería’s display at the Madrid exhibition and may have arrived in Vilanova after the end of the exhibition.

Estimation of provenance

The wooden macana described as ‘Macana of Ayonique. Defence of the Indians’ is an object from the island of Yap, in the Caroline Islands, which reveals the complexity of the processes of collection and display in the Spanish colonial context. According to the inventory of the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB), the object is considered rare and there is no detailed contextualization information. In order to reconstruct its arrival in Vilanova i la Geltrú, it is essential to understand the role of Víctor Balaguer and the impact of the 1887 Philippines Exhibition in Madrid.

Víctor Balaguer, founder of the BMVB, was an outstanding figure, with multiple facets as a politician, writer and cultural patron. In addition to his passion for the Philippines, Balaguer was a fervent defender and promoter of Filipino culture and its collections. During his third term as Minister of Overseas, he organized the Philippines Exhibition, which served to showcase the diversity and richness of the Spanish colonies. This exhibition held in Madrid in 1887 had a great impact on public perception and Spanish colonial policy. In addition to showcasing military successes in the Philippines, it facilitated the integration and dissemination of exotic material from the colonies, including weaponry and cultural artefacts. The exhibition featured objects not only from the Philippines, but also from other Spanish colonies. The National Archaeological Museum displayed a diverse collection of objects—mainly from the Philippines, but also from Puerto Rico and Fernando Poo—while the Museo de Artillería displayed numerous objects from the Caroline Islands.

The macana in question was part of the collection exhibited by the Museo de Artillería at the Philippines Exhibition. In this context, it is plausible that the object now in Vilanova is one of the Carolinian macanas on display, as documented in the exhibition catalogue. The Butlletí de la BMVB of July 1887 mentions that many of the objects in the exhibition would be given to the institution in gratitude to Balaguer, suggesting that the macana may have come to Vilanova as part of this donation.

Furthermore, correspondence and records from the period indicate that several objects from the exhibition were sent to Vilanova between October 1887 and February 1888. This flow of objects helps to explain how the macana arrived at the BMVB, despite inconsistencies in the inventories and a possible lack of detailed documentation.

Possible alternative classifications

Based on the results of this research, the following data can be updated in the inventory:

Brief institutional description: Macana, mace

Place of acquisition: Caroline Islands (now Federated States of Micronesia)

Place of production/origin: Ayonique, island of Yap

Collector: Museo de Artillería (Philippines Exhibition)

Donor or seller: Víctor Balaguer

Classification group: Yapese

Date of acquisition by the institution: late 1887 – early 1888

Complementary sources

Álvarez Guerra, J. (1887). Viajes por Filipinas: De Manila a Marianas. Madrid: Imprenta de Fortanet.

Archivo Histórico Nacional (1885). Crean el Gobierno Político de las Islas Carolinas y Palaos con Enrique Capriles Osuna al frente (ES.28079.AHN/16//ULTRAMAR, 5346, Exp.19).

Balaguer i Cirera, V. (1886-1888). Correspondencia reservada con el Gobernador general de Filipinas. Fons general, signatura 5 Ms. 113. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Víctor Balaguer (1a època, 26 de juliol de 1887), (34). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

Crailsheim, E. (2021). Ambivalencias modernas. Guerra, comercio y «piratería» en las relaciones entre Filipinas y los sultanatos colindantes a finales del siglo XVIII. Madrid: Polifemo.

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas Madrid (1887). Catálogo de la Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid … el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Fernández Palacios, J. M. (2024). La crisis de las islas Carolinas de 1885 analizada desde Filipinas. Ayer. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, 134(2), 169-193. <https://www.revistasmarcialpons.es/revistaayer/article/view/fernandez-la-crisis-de-las-islas-carolinas-de-1885/2631>.

González Enríquez, M. C. (1995). Las Indias olvidadas: Orígenes de las piezas de Oceanía en el Museo de América. Anuales del Museo de América, 3, 91-95.

La Ilustración española y americana (8 d’octubre de 1881). Any XXV, (37), 29.

Lezcano, F. (1887). Descripción de las islas Carolinas. Madrid: Imprenta de Fortanet.

Miguel, G. (1887). Estudios sobre las islas Carolinas. Madrid: Imprenta de José Perales y Martínez.

Montero y Vidal, J. (1888). Historia de la piratería Malayo-mahometana en Mindanao, Joló y Borneo. Fons general, signatura SL 5725-5726. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Sánchez Gómez, L. Á. (2003). Un imperio en la vitrina: El colonialismo español en el Pacífico y la Exposición de Filipinas de 1887. Madrid: CSIC Press.

Taviel de Andrade, E. (1887). Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid en 1887 (2 vol.). Madrid: Imprenta de Uliano Gómez y Pérez.