Summary of results

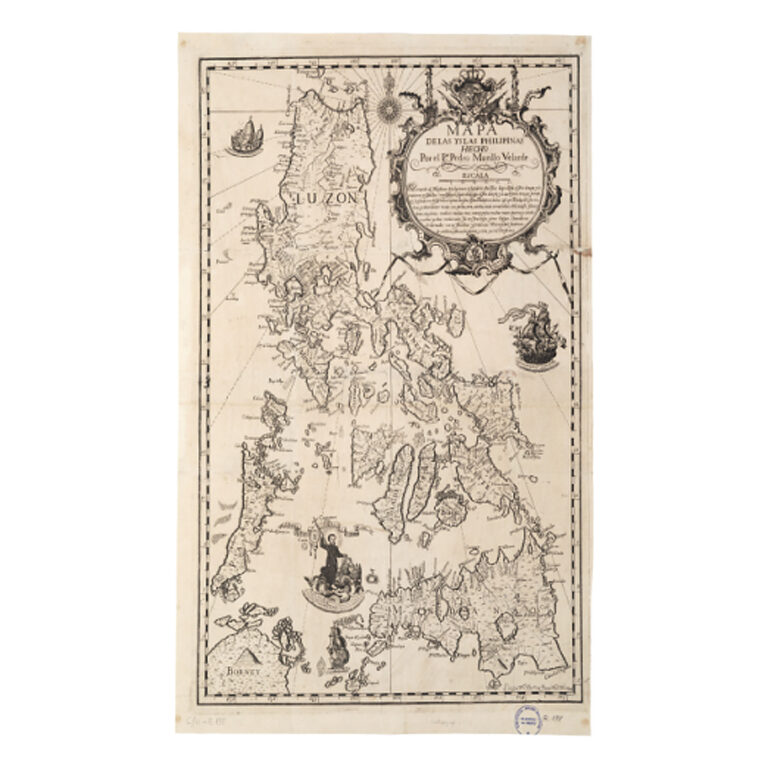

Pedro Murillo Velarde’s map of the Philippine Islands, known as the ‘mother of all Philippine maps’, is a historical and cultural symbol that reflects the complexities of Spanish colonialism in the Philippines. Created in 1734 by Murillo Velarde, a Spanish Jesuit, in collaboration with Filipino engraver Nicolás de Cruz Bagay, it is a testament to the geography, cultural diversity, and trade routes of the Philippine archipelago during the colonial era. The map itself is an important element in the construction of the identity of the Filipino nation.

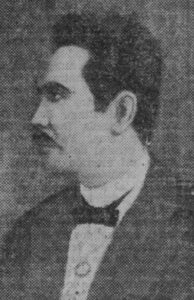

During the 19th century, the Philippines underwent economic and social transformations due to the expansion of international trade and foreign investments. Iloilo, the second most important city in the archipelago, benefited significantly from this due to its strategic port. In this context, Crisanto Pineda, a lawyer, stood out as a prominent figure; he was born in Tondo, Manila, and moved to Iloilo, where he became a lawyer, journalist, and businessman. Pineda, of mixed Chinese and native Filipino descent, was part of a local elite that sought to rise in the colonial hierarchy. Despite his successes, he faced challenges because of his mixed ancestry, which led him to fight for recognition of his rights and status.

Crisanto Pineda travelled to Spain in 1887 with several objectives in mind. First, he sought to validate his law degree from the Real Audiencia de Filipinas (Royal Court of the Philippines) in order to obtain a degree in Canon and Civil Law in Spain, which was important for his professional recognition and to increase his income. He also wanted to settle legal disputes related to his business activities in Iloilo and to obtain a noble title to raise his social status. In February 1888, Pineda received a Real Despacho de Nobleza y Armas, an official document which gave him the nobility title of hidalgo, an unusual achievement for a mestizo of Sangley origin (an archaic term used in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era to describe people of mixed Chinese and native Filipino descent) in the colonial social hierarchy.

During his stay in Spain, Pineda met Víctor Balaguer, who was then Minister of Overseas, and showed interest in the Philippine collections in the museum library in Vilanova i la Geltrú. Pineda visited the library before returning to Manila and, in gratitude, decided to donate a copy of José Rizal’s Noli me tangere. Subsequently, he sent the library a copy of Murillo Velarde’s 1788 version of the map, highlighting its historical importance. Pineda’s procurement of the map is shrouded in mystery, but it reflects his intention to preserve and share Filipino culture with the world, and why not, to spread the critical sense of the Filipino people who increasingly demanded change and improvement.

Crisanto Pineda’s decision to donate the map can be understood in the context of his personal, professional and socio-political interests, as well as his desire to leave a significant legacy. A fundamental reason was the consolidation of his social and professional status. Pineda had worked hard to improve his position in the colonial hierarchy and the donation may have been a strategic gesture to strengthen his relations with influential figures such as Víctor Balaguer. It is also important to consider the network of contacts and shared masonic alignment with Balaguer, which could have facilitated a relationship of trust and collaboration.

In making the donation, Pineda ensured that his name would be associated with an act of cultural preservation, providing him with a sense of legacy and lasting contribution to Philippine history. Pineda’s letter to Balaguer, thanking him for the recommendations the minister had provided, suggests that he saw Balaguer as an ally and benefactor. The donation of the map may have been an act of reciprocity to strengthen this relationship and gain further support for his causes.

In conclusion, Crisanto Pineda’s donation of the Murillo Velarde map to Víctor Balaguer was probably a multifaceted act that combined his personal aspirations, an interest in promoting the Filipino culture, and a desire to establish strategic connections in a complex political and social environment. Through this donation, Pineda not only contributed to the preservation of an important cultural heritage, but also cemented his place in history as a key player in the dissemination of the Filipino legacy in Europe.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

The map of the Philippine Islands by Pedro Murillo Velarde in the BMVB is a copy of the third version of the document, drawn up for the work Historia general de Philipinas, conquistas espirituales y temporales de estos españoles dominios del frare agustí Juan de la Concepción, produced in 1788. The first version of the map was created in 1734 at the request of King Philip V in order to obtain a more detailed knowledge of the Spanish possessions in the Philippine archipelago. This cartographic accuracy was part of an effort to exercise effective colonial control over a territory, whose cultural diversity and indigenous resistance challenged imperialist pretensions. Immediately, the map produced by Jesuit Pedro Murillo Velarde (1696–1753) and Filipino engraver Nicolás de Cruz Bagay became a reference map of the Philippine archipelago.

In 1744, Murillo and Bagay produced a second edition of the map. This version, intended for inclusion in Murillo’s Historia de la Provincia de Filipinas de la Compañía de Jesús, published in 1749, was smaller in scale and did not include the ethnographic cards of the original map. It provided updated navigational routes and geographical details, including new settlements in Luzon. It also included symbolic depictions, such as St Francis Xavier as Prince of the Seas, an added detail that underlines the connection between evangelization and Jesuit cartography.

In 1767, King Charles III ordered the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from all Spanish dominions, including the Philippines. The order arrived in 1768, and the Jesuit possessions were transferred to other religious orders. The original copper plates of the map remained in the custody of the San Carlos Seminary in Manila. These plates were modified in 1788 to include Murillo Velarde’s map in the first volume of the Augustinian Juan de la Concepción’s work, this time without references to the Society of Jesus—a reflection of the political tensions generated by the expulsion of the Jesuits. This edition is one of the rarest and most coveted because of the alterations to the original plate and the scarcity of current copies.

The Society of Jesus was restored in Spain in 1852, returning to the Philippines in 1859, under the reign of Isabella II, to reactivate their missionary and educational activities, especially in Mindanao and Jolo, areas of resistance to evangelization because of the Muslim sultanate’s opposition to colonial rule. Upon their return, the Jesuits recovered some of their property, including the copper plates of the map, and in 1887 published a new edition of the map, restoring the recovered plates. This fourth version was presented at the Philippines Exposition in Madrid in 1887, along with other ethnographic maps.

In 2014, a copy of the 1734 map was auctioned at Sotheby’s, London. The map, preserved for more than two centuries by the Duke of Northumberland’s family, was put up for sale to cover the cost of a £12 million repair due to the collapse of a drainage system. It was purchased by Filipino businessman Mel Velarde for 231,000 euros, who donated it to the National Museum of the Philippines. Until that time, there were no copies of the map in the country, and its repatriation was considered significant for Philippine national identity.

Over the past decade, the map has played a crucial role in territorial disputes between the Philippines and China over sovereignty over the Scarborough Shoal, located in the South China Sea. During the 2012 standoff, the Philippine government presented Murillo Velarde’s map as evidence before the Hague Tribunal to prove its sovereignty over the territory. Murillo’s map shows Panacot (Scarborough) as part of the territory under Spanish sovereignty, bolstering the Philippine’s arguments in the dispute. This use of the map underlines its continuing importance as a historical document and political tool on the international stage.

As the BMVB inventory describes, the map was donated by Crisanto Pineda. This donation is published in the BMVB’s bulletin of November 1888, on page 8:

‘A precious and very rare Map of the Philippine Islands made by Fr. Pedro Murillo Velarde of the Society of Jesus and sculpted, apparently in strong water, by Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay in Manila, in the year 1744, has become part of our collections thanks to the nobility and generosity of Mr. Crisanto Pineda, a person worthy of our consideration for the continued favours he has shown to this LIBRARY-MUSEUM’.

The figure of Crisanto Pineda is a good example of the consequences of a long process of colonization based on racial differentiation and segregation. It is quite likely that, as we shall see below, Crisanto Pineda ended up meeting Víctor Balaguer in Madrid in 1888.

Pineda was a lawyer by profession in the second most important city of the archipelago during the Spanish colonial period, Iloilo, on the island of Panay, a city that throughout the 19th century received important investments to develop trade relations through its port. He was born (at an unknown date) in the head of Tondó, now a district of the city of Manila. In 1872, he obtained a law degree from the Real Audiencia de Flipinas in Manila. In 1879 (Guía Oficial de Filipinas, 1879: 84) he was already practising in Iloilo, where he was also a journalist and businessman. He was a correspondent of La Ilustración de Oriente in 1872, and later of Oriente in 1877. In 1885, he was a contributor to the Libreria Universal de Manila, a library also in Iloilo. In 1886, together with a Spanish illustrator, Francisco Gutiérrez Creps, assistant to the Cuerpo de Montes, he founded the Eco de Panay, a biweekly newspaper which in two years would become a weekly, with its own printing press, and which would remain active until 1898.

We have few references to his activity as a businessman. We have an interesting letter written by Pineda himself and published in La Oceanía Española (no. 238, 14 October 1884: 3), addressed to the editor of the Porvenir de Visayas, with the aim of defending himself against the slander that, according to the author, was being heaped upon him. The letter highlights his legal knowledge, and constitutes a real plea in defence of his business activities, which are enumerated throughout the missive. First, he defends the rates he charged as a carriage contractor (citing a minimum of three types: four-wheeled carriages, buggies, two-horse omnibuses, etc.). He then went on to mention his activity as a ford landlord and the first bridge (built by himself) between Iloilo and La Paz, for which he managed the tolls.

The question of fords and bridges was a delicate matter, and involved constant conflicts between authorities, businessmen and private individuals, as can be seen in the press of the time and in the regulations and lawsuits. The large number of rivers in the Philippine geography posed a logistical challenge to the colony’s commercial expansion, a profit opportunity for private enterprise, and created needs for the population. In the vast majority of cases, the management of the fords was controlled by European Spaniards and a mixed-race upper class, to which Pineda belonged, who were the only ones capable of submitting proposals adapted to the complex specifications. He was also in charge of managing the fords on the bridges from Molo to Mandurriao, and from Jaro to Mandurriao, even though in these cases the bridges were public.

The issue of fords and tolls continued to be on the agenda throughout the period from 1883 to 1887, during which Pineda was awarded the contract for the ford service in the province of Iloilo. As dialogue with the colonial administration did not resolve the accumulated grievances against him, Pineda, during his stay in Madrid, contacted the Minister of Overseas directly, in January 1888, to intercede on his behalf. We do not know whether Víctor Balaguer’s reply was satisfactory to the Filipino lawyer, but this letter shows for the first time the existence of a certain relationship with the minister (National Historical Archive [AHN], Fondo de Ultramar, file 5347, dossier 18).

The reason is that, despite being an important figure in Iloilo, with Spanish surnames and recognized by the authorities, for census purposes, Pineda was part of the Sangley mestizos, as the mixed population of Chinese and indigenous blood was commonly known in the Philippines, who were subject to specific tributes.

Indeed, four Spanish surnames converged in the person of Pineda, all linked to the conquests of Mexico and the Philippines (Pineda Domingo Fernando y Casas). One of his ancestors had been Ambrosio Casas, Pineda’s maternal great-grandfather. Born in Binondo, he was a colonel of the mestizo provincial militias of the Royal Prince, Barangay chief and ‘gobernadorcillo’ (literally ‘little governor’) of mestizos in Binondo. Decorated with the Grand Cross of Isabella the Catholic, he participated in the erection of the statue of Charles IV in front of the Manila Cathedral between 1811 and 1825. On 21 May 1817, he was granted a royal decree with the privilege that his descendants, even his grandchildren, would be recognized as European Spaniards:

‘[…] I have come to grant to the aforementioned D. Ambrosio Casas in attention to his merits the grace that his children and his first grandchildren do not pay the contributions that the mestizos of Sangley pay and that they are exempted from poles and services as if they were European Spaniards […]’ (La Vanguardia. Diario filipino independiente, year XXIV, no. 149, 25 July 1933: 11).

He was thus exempt from the taxes imposed on mestizos of Chinese origin. His daughter, Lucía Casas, married Damián Domingo, a naval second lieutenant and one of the first Filipino painters of which we have records (Santiago, 2010). A well-known portrait painter, Domingo’s most famous speciality was his illustrations on types and costumes, known as ‘tipos del país’ (literally, guys of the country), watercolour drawings depicting native figures of all social classes and ethnic groups. This couple had a prolific offspring (closing in that generation the privilege granted to his grandfather), among them Feliciana Domingo, married to Anselmo Pineda, Crisanto’s mother and father respectively. As a lieutenant of Cavalry and knight of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Hermenegildo (of which only decorated military personnel were members). In 1868, Anselmo Pineda submitted an application requesting that his sons be considered Spanish (AHN, Fondos de Ultramar, dossier 472, file 36). In this way, they were eligible for scholarships to study at colleges. However, the laws only allowed scholarships for children of Spanish and European fathers and mothers, so despite Lieutenant Pineda’s military dossier, the request was rejected.

So, Crisanto Pineda, lawyer, prominent businessman in Iloilo City, journalist, descendant of a nobleman, no longer had the right to be exempted from taxes due because of his Sangley status. In April 1887, he was making powers of attorney in Iloilo and, after collecting numerous documents, he embarked in May on the steamship Diamante with the son of his first marriage, bound for Hong Kong, Marseille, and Barcelona (La Oceanía Española, year XI, no. 104, 8 May 1887: 3). In all likelihood, he arrived in Madrid before the end of the exhibition on his country that was being organized in the Retiro Park. And as early as December 1887, he wrote a letter to Víctor Balaguer, then Minister of Overseas, requesting the validation of his degree as a lawyer of the Real Audiencia de Filipinas for that of Licentiate in Canon and Civil Law, setting out legal precedents for its validation. We do not know if Crisanto Pineda had the opportunity to meet the minister during the holding of the exhibition, although it is certain that Pineda did not only travel to Madrid to validate his law degree.

On 6 February 1888, a Real Despacho de Nobleza y Armas was issued in his favour, an official document that determined that from that moment on, Pineda would no longer be considered a Sangley, would carry a coat of arms and would be considered a hidalgo. Only two non-native Spaniards are known to have been distinguished with a nobility title in the Philippines; Antonio Tuason de Binondo and Crisanto Pineda (Santiago, 2010: 14), both Sangley mestizos.

In April 1888, he was received by the Queen Regent of Spain, and was awarded the Encomienda de Isabel la Católica, an honour award. Although the circumstances of his proximity to, or friendship with, Víctor Balaguer are unknown, Pineda wrote to him on 25 May 1888, already from Barcelona, to announce that he had visited the library museum in Vilanova i la Geltrú and that he had been very impressed by the Philippine collection that it housed at the time. It was during this visit that Pineda made his first donation to the BMVB, a copy of Noli me tangere by José Rizal.

Both Filipinos had in common with Balaguer their membership of Masonry, something that may have worked in Pineda’s favour in facilitating his link with the Minister of Overseas. He was grateful for the recommendations the minister had given him and reaffirmed his commitment to contribute to the expansion of the museum’s collection. On the first of June, he left Barcelona for Manila, where he arrived the fourth of July. There he received a letter from Víctor Balaguer and was cordially received by the governor general.

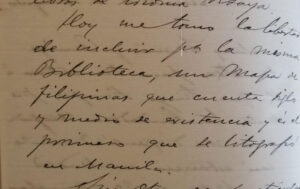

From his arrival in the Philippines, Pineda made use of his noble coat of arms, which he began to include in his letters to Víctor Balaguer. In the first letter he sent from the Philippines, Pineda lamented Balaguer’s dismissal as Minister of Overseas, and at the same time informed him of his first shipment, in this case of a wooden table (see specific report), leaving it in Balaguer’s hands to decide what use he wished to make of it. In September, a new letter to the former minister informed him of a first donation of books for the museum, and on 9 October, a third letter referred to new donations. Among them was the following:

‘Today I take the liberty of including for the Library itself, a map of the Philippines which has existed for a century and a half and is the first to be lithographed in Manila’ (handwritten letter from Crisanto Pineda to Víctor Balaguer, Ms. 385/064: 2).

We do not know how or in what way Pineda came into possession of the map. It is possible that copies were printed in the Philippines after the 1788 modification. We rule out the possibility that he acquired it from the Jesuits themselves, because in 1887 the copper plates had been modified to restore the name of the company, making it impossible to obtain a ‘censored’ copy produced after that date. Despite the scant information provided by Pineda himself, he was well aware of the importance of the donation, which is why he emphasized it in his correspondence with his friend and, perhaps, benefactor.

Pineda’s last letters to Balaguer showed the complexity of the bond between them. In January 1889, Pineda informed him of his recent marriage to a daughter of Eduardo Aulés, whom Pineda described as his interlocutor’s ‘protégé’, announcing that his new father-in-law would soon be travelling to Madrid on the occasion of his appointment as clerk of the Audiencia de Cebu. He also mentioned the Barcelona Universal Exposition, which he seemed to have had the opportunity to visit fleetingly before returning to the Philippines, during the days when he had also visited Vilanova. In his last letter, a month later, he asked for Balaguer’s support in obtaining a post at the Land Registry Office opened in Iloilo.

At the same time as their epistolary relationship, presided over by mutual admiration and adulation, the dossier for the recognition of his law degree was slowly being processed in Madrid. The dossier, dated 30 December 1887, seemed to be at a standstill throughout 1888. Perhaps Pineda’s father-in-law interceded during his stay in Madrid to unblock the process? The fact is that on 22 May 1889 the General Government of the Philippines was notified of the existence of a royal order informing it of the proceedings. Whatever the case, it is very likely that Crisanto Pineda did not know about it. The Philippines experienced six cholera epidemics during the 19th century, and the last one was one of the deadliest (200,000 victims).

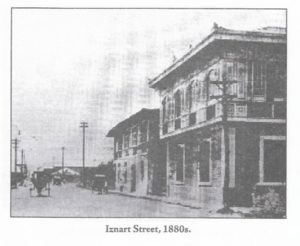

From April 1889, cases began to increase in all parts of the archipelago. On 19 May, the governor of Iloilo asked Pineda to rent his house on Iznart Street to set up a field hospital (La Oceanía Española, year XIII, no. 115, 19 May 1889: 3). Pineda altruistically gave up his property, but six days later he died of cholera. A ship arriving in Manila from the island of Panay on 1 June confirmed, among many others, the hidalgo’s death (ibidem: 2).

In conclusion, it should be added that the dossier was rejected in December of that year. Among the arguments put forward, it was recalled that any validation process required both the payment of the corresponding fees and the passing of exams, which Pineda had tried to avoid. Finally, the report issued by the University of Manila, the institution responsible for issuing the final decision, was conclusive: the final reason was the petitioner’s lack of interest caused by his death.

Crisanto was part of a local elite that sought to equate itself with the native Spaniards, in his case to the point of attaining a noble title. The multiple businesses he headed, as well as his place of residence—a house with a small chapel in Iznart Street, in the centre of the city—reflected a lineage built up over generations of collaboration with the colonizers, but also with a critical view of the new times in which he had to live. It is not wihtout significance that its first donation was Rizal’s first work, delivered to the BMVB a year after it had been described as ‘subversive’ by Governor General Emilio Terrero. Perhaps Rizal’s copy met the same fate as its author? Despite the publication in the museum’s bulletin, there is no record in the library of the book’s whereabouts.

Estimation of provenance

Pedro Murillo Velarde’s map of the Philippine Islands, known as the ‘mother of all Philippine maps’, is a historical and cultural symbol that reflects the complexities of Spanish colonialism in the Philippines. This map, in 1734 by Murillo Velarde, a Spanish Jesuit, in collaboration with Filipino engraver Nicolás de Cruz Bagay, it is a testament to the geography, cultural diversity, and trade routes of the Philippine archipelago during the colonial era.

During the 19th century, the Philippines underwent a series of economic and social transformations due to the expansion of international trade and foreign investments. Iloilo, the second most important city in the archipelago at the time, benefited significantly from these investments thanks to its strategic port, facilitating trade relations with other regions and the outside world.

In this context, Crisanto Pineda, a lawyer by profession, emerged as a prominent figure. Born in Tondo, Manila, Pineda moved to Iloilo, where he excelled as a lawyer, journalist, and businessman. Pineda, a mestizo of Sangley origin (an archaic term used in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era to describe people of mixed Chinese and native Filipino descent), was part of a local elite seeking to rise in the colonial hierarchy. Despite his successes—such as obtaining a law degree from the Real Audiencia de Filipinas in 1872—and his many entrepreneurial activities, he faced challenges because of his mestizo ancestry, which led him to fight for recognition of his rights and status.

Crisanto Pineda travelled to Spain in 1887 with several objectives in mind. Firstly, he sought to validate his law degree from the Real Audiencia de Filipinas in order to obtain a degree in Canon and Civil Law in Spain. Such validation was important to ensure his professional recognition and to increase his income. In addition, Pineda was interested in settling various legal disputes related to his business activities in Iloilo, where he had been involved in disputes over the management of barriers and tolls, as well as his activities as a contractor and businessman. Another significant reason for his trip was to obtain a noble title, reflecting his aspiration to elevate his social status in the colonial context. In February 1888, Pineda received a Real Despacho de Nobleza y Armas that allowed him to be considered a hidalgo, an unusual achievement for a Sangley mestizo in the colonial social hierarchy.

During his stay in Spain, Pineda met Víctor Balaguer, then Minister of Overseas, and showed interest in the Philippine collections of the museum library in Vilanova i la Geltrú. Pineda visited the BMVB before returning to Manila and was impressed by its Philippine collection. As a token of his gratitude and collaboration, Pineda decided to donate a copy of José Rizal’s Noli me tangere during his visit to the museum. Subsequently, he sent a copy of Murillo Velarde’s map to the library from the Philippines, highlighting the antiquity and historical importance of the document.

The arrival of the map in Catalonia is shrouded in mystery, as it is not known exactly how Pineda obtained the copy. However, it is likely that, after the 1788 modification, additional copies were printed in the Philippines. Given that by 1887 the original copper plates had been modified to restore the name of the Society of Jesus, it is unlikely that the ‘censored’ copy was produced after this date. The map was sent to Vilanova along with other Philippine documents and books, reflecting Pineda’s intention to preserve and share Filipino culture with the world. This donation underlines his commitment to the recognition and dissemination of Filipino cultural heritage, despite the complexities of his own mestizo identity and the challenges he faced in the colonial context.

Crisanto Pineda’s decision to donate the map the Murillo Velarde map to the BMVB can be understood in the context of his personal, professional and socio-political interests, as well as his desire to leave a significant legacy. One of the fundamental reasons for donating the map was to consolidate his social and professional status. Pineda, a mestizo of Chinese and Spanish origin, had worked hard to improve his position in the colonial hierarchy. During his trip to Spain, he sought to validate his law degree and obtain formal recognition of his social status by receiving a Real Despacho de Nobleza y Armas. Murillo Velarde’s donation of the map may have been a strategic gesture to strengthen his ties with influential figures such as Víctor Balaguer, the Minister of Overseas, who had the capacity to facilitate such goals.

Furthermore, Pineda showed a genuine interest in preserving and disseminating Filipino culture, as evidenced by his donation of a copy of José Rizal’s Noli me tangere during his visit to the museum. By donating the map, Pineda was contributing to a collection that highlighted the cultural heritage of the Philippines in Europe, underscoring the archipelago’s rich history and its relevance in a global context. It is also important to consider the network of Masonic contacts and alignment that both Pineda and Balaguer shared. Such connection through Freemasonry could have facilitated a bond of trust and collaboration. This ideological and social alignment could have motivated Pineda to choose Balaguer as the recipient of a cultural object of great value and significance.

On the other hand, by making this donation, Pineda ensured that his name would be associated with an act of cultural preservation, which gave him a sense of legacy and lasting contribution to Philippine history and culture. Securing a place in history as a cultural benefactor would have been a powerful motivation for someone of his position and background. Finally, Pineda’s letter to Balaguer thanking him for the recommendations the minister had provided suggests that Pineda saw Balaguer as an ally and benefactor who could help him in his personal and professional goals. The donation of the map may have been an act of reciprocity to strengthen that relationship and gain further support for his causes.

In conclusion, Crisanto Pineda’s donation of the Murillo Velarde map to Víctor Balaguer was probably a multifaceted act that combined his personal aspirations, his interest in promoting the Filipino culture, and his desire to establish and maintain strategic links in a complex political and social environment. Through this donation, Pineda not only contributed to the preservation of an important cultural heritage, but also cemented his place in history as a key player in the dissemination of the Filipino legacy in Europe.

Possible alternative classifications

Regarding the information on the map, it would be necessary to date it correctly in the inventory. Furthermore, if it is to be exhibited, it would be advisable to contextualize how it arrived at the museum, including a decolonial analysis of the causes that may have led to the donation.

Complementary sources

Aguilera Fernández, M. (2018). La reimplantación de la Compañía de Jesús en Filipinas: De la restauración a la revolución filipina (1815-1898) [tesi doctoral, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona]. <https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/imprimirFicheroTesis.do> [consulta: 19-08-2023].

Agustinos Recoletos (11 de febrer de 2021). Fray Juan de la Concepción, agustino recoleto e insigne historiador. <https://www.agustinosrecoletos.org/actualidad/17938/fray-juan-de-la-concepcion-agustino-recoleto-e-insigne-historiador> [consulta: 12-08-2023].

Altić, M. (2018). Jesuit contribution to the mapping of the Philippine Islands: A case of the 1734 Pedro Murillo Velarde’s Chart. Dins Martijn Storms et al. (ed.), Mapping Asia: Cartographic Encounters Between East and West. Cham: Springer. <https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-90406-1_5> [consulta: 08-07-2023].

Archivo Histórico Nacional, fons d’Ultramar, lligall 5347, exp. 18.

Artigas y Cuerva, M. (1902). Los periódicos filipinos: La más completa bibliografía publicada hasta la fecha acerca de los papeles públicos filipinos [microfilm]. Manila: Biblioteca Nacional Filipina. <https://archive.org/details/arb8044.0001.001.umich.edu/mode/2up> [consulta: 21-08-2023].

Balaguer, V. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Víctor Balaguer a Joan Oliva. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura: Oliva/437. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Balaguer (26 de novembre de 1888). Any I, (50), 8. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

Concepción, Fray Juan de la (1788). Historia general de Philipinas, conquistas espirituales y temporales de estos españoles dominios, establecimientos progresos y decadencias: comprehende los imperios reinos y provincias de islas y continentes con quienes há havido communicacion y comercio por immediatas coincidencias: con noticias universales geographicas hidrographicas de historia natural, de politica de costumbres y de religiones… Manila: Impr. Del Seminar. Conciliar y Real de S. Carlos. Fons general, signatura XVIII/451. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Díaz, C. (19 de gener de 2019). Damián Domingo, pintor y maestro filipino. Cuaderno de Sofonisba. <http://cuadernodesofonisba.blogspot.com/2019/01/damian-domingo-pintor-y-maestro-de.html> [consulta: 22-08-2023].

Díaz de la Guardia y López, L. (2001). Datos para una biografía del jurista Pedro Murillo Velarde y Bravo. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, sèrie IV H.ª Moderna, XIV, 407-471.

Esquire Philippines (4 de maig de 2017). We have the mysterious map that proves the West Philippine Sea is ours. Esquire Magazine. <https://www.esquiremag.ph/politics/news/mel-velarde-murillo-map-a00203-20170504-lfrm> [consulta: 11-08-2023].

Expedient de beca dels fills d’Anselmo Pineda. Archivo Histórico Nacional. Fons d’Ultramar, lligall 472, exp. 36.

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas (1887). Catálogo de la exposición general de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid… el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España. <http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000046951> [consulta: 25-08-2023].

González Cabrera Bueno, J. (1734). Navegacion especulativa, y practica, con la explicacion de algunos instrumentos, que estan mas en uso en los navegantes, con las reglas necesarias para su verdadero vso… Manila: Convento de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de la Orden de Nro. Seraphico Padre San Francisco.

Guardiola, J. (2006). El imaginario colonial: Fotografía en Filipinas durante el período español 1860-1898. Barcelona: Casa Asia.

Jesuïtes (1887). Cartas de los PP. de la Compañía de Jesús de la Misión de Filipinas. Cuaderno 6.º. Manila: M. Pérez, hijo. Fons general, signatura SL 22293. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Jesuïtes (1887). Cartas de los PP. de la Compañía de Jesús de la Misión de Filipinas. Cuaderno 7.º. Manila: M. Pérez, hijo. Signatura HA/10028. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España. <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000047409&page=1> [consulta: 20-08-2023].

La Ilustración de Occidente (7 d’octubre de 1877). Any I, (1), 2. Hemeroteca Municipal de Madrid, signatura 651/3.

La Oceanía Española (14 d’octubre de 1884). Any VIII, (238). <https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/publicaciones/verNumero.do?idNumero=1000746708> [consulta: 21-08-2023].

—(8 de maig de 1887). Any XI, (104), 3. <https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=392123&posicion=3&presentacion=pagina> [consulta: 22-08-2023].

—(19 de maig de 1889). Any XIII, (115), 3. <https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=316387&posicion=3&presentacion=pagina> [consulta: 22-08-2023].

—(1 de juny de 1889). Any XIII, (125), 2. <https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=316397&posicion=2&presentacion=pagina> [consulta: 22-08-2023].

La Vanguardia. Diario filipino independiente (25 de juliol de 1933). Any XXIV, (149), 11. <https://prensahistorica.mcu.es/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=1000379954&posicion=11&presentacion=pagina> [consulta: 20-08-2023].

Medina, J. T. (2000). Historia de la imprenta en los antiguos dominios españoles de América y Oceanía (vol. II). Alacant: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. <https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/historia-de-la-imprenta-en-los-antiguos-dominios-espanoles-de-america-y-oceania-tomo-ii–0/html/> [consulta: 08-08-2023].

Murillo Velarde, P. (1752). Catecismo ó instruccion christiana, en que se explican los mysterios de nuestra sante fè, y se exhorta a huir de los vicios y abrazar las virtudes / lo escribia el P. Pedro Murillo Velarde, de la Compañia de Jesus, procurador general de la provincia de Philipinas… Madrid: Imprenta de los Herederos de Francisco del Hierro.

—(1752). Geographia Historica [en línia]. Madrid: En la Oficina de D. Gabriel Ramírez [et al.], I, cap. 1, p. 1. <https://www.bibliotecavirtualdeandalucia.es/catalogo/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=88492> [consulta: 16-07-2023].

—(1752). Geographia historica, de las islas philipinas, del africa, y de sus islas adyacentes [en línia]. Madrid: En la Oficina de D. Gabriel Ramírez [et al.], VIII, foli 71. <https://books.google.es/books?id=8Nl5DlMZS9YC&printsec=frontcover&hl=es&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false> [consulta: 09-07-2023].

—(1749). Historia de la Prouincia de Philipinas de la Compañía de Iesus: segunda parte, que comprehende los progresos de esta Prouincia desde el año 1616 hasta el de 1716 / por el P. Pedro Murillo Velarde de la Compañia de Iesus … Manila: Imprenta de la Compañía de Iesús, por D. Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay. <https://books.google.es/books?id=8Nl5DlMZS9YC&printsec=frontcover&hl=es#v=onepage&q&f=false> [consulta: 09-07-2023].

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer. <https://cataleg.victorbalaguer.cat/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=145507&query_desc=kw%2Cwrdl%3A%20Mindanao> [consulta: 26-08-2023].

—(1888). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/651. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Pardo Tavera, T. H. (1893). Noticias sobre la imprenta y el grabado en Filipinas. Madrid: Hijos de M. G. Fernández. <http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000120192&page=1> [consulta: 12-08-2023].

—(1894). El mapa de Filipinas del P. Murillo Velarde. Manila: Chofré y Comp. Fons general, signatura F912/1. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Pineda, C. (1888). Carta manuscrita de Crisanto Pineda a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura: 8800512. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

—(1888). Carta manuscrita de Crisanto Pineda a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura: 8800815. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

—(1888). Carta manuscrita de Crisanto Pineda a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura: Ms. 385/064. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

—(1889). Carta manuscrita de Crisanto Pineda a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura: 8900603. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

—(1889). Carta manuscrita de Crisanto Pineda a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Víctor Balaguer, signatura: 8900109. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

The Scots Magazine (1763), 25, 235. <https://books.google.es/books?id=vtg5AQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=es#v=onepage&q&f=false> [consulta: 13-08-2023].

Valdés Tamón, F. (1733). [Carta de Valdés Tamón sobre mapes de Murillo Velarde-còpia]. Manila. FILIPINAS,384,N.24/UI-Correspondencia de los gobernadores con la vía reservada/1D-Audiencia de Filipinas/Sc-Gobierno. Sevilla: Archivo General de Indias. <https://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/description/3629807> [consulta: 16-07-2023].

Villoria Prieto, C. (2015). La producción cartográfica del jesuita Pedro Murillo Velarde (1696-1753). Dins F. L. de la Puente i F. J. Mateos Ascacíbar (ed.), El siglo de las Luces: III Centenario del Nacimiento de José de Hermosilla (1715-1776), XVI Jornadas de Historia en Llerena. Llerena: Sociedad Extremeña de Historia.