Summary of results

According to our provenance research, this helmet may have belonged to the datu (local leader) Aliubdin (this is the spelling that appears in numerous documents of the period). Aliubdin was one of the two candidates for the Sulu throne after the death of Badaruddin II in February 1884. He was a datu loyal to the Spanish regime and had been residing in the village of Matanda since January 1884, where he had received Spanish support to build his infrastructure. After Badaruddin II’s death, Aliubdin attempted to proclaim himself Sultan, but was dissuaded by the Spanish Army and was told to move his residence to Patikul and proclaim himself Sultan there.

The Spanish government in Jolo sent a delegation to dissuade Aliubdin, but he and his followers insisted on the proclamation. On 13 March 1884, Aliubdin moved to Patikul and was proclaimed Sultan there. This resulted in the simultaneous existence of two sultans in Sulu until 1886 when Governor-General Emilio Terrero appointed the datu of Palawan, Muhamad Harun ar-Rashid, as sultan. Harun’s imposition provoked a war with the sultanate that caused numerous losses among the Joloans. Harun abdicated in 1893, and Amirol Quiram was eventually proclaimed sultan of the archipelago.

A helmet and coat of mail set was exhibited at the Philippines Exhibition, which appears in the Catalogue of the Philippines Exhibition in group 24, presented by the exhibitor Diego de Saavedra, with the following description:

‘Helmet and coat of mail belonging to the Sultan of Patticolo, datto Alit-mudin, candidate to the Sultanate of Jolo; the helmet, the only piece known on the island, belonged to his ancestors, two centuries after its use disappeared; it was acquired in the ranchería of Matanda, residence of the said datto’.

The status of Aliubdin and his helmet is uncertain. It is possible that Aliubdin released his helmet and coat of mail as a guarantee of compliance with the recommendations of the military delegation, which may have forced him to leave Matanda and take his belongings with him. The lack of confirmation of these events suggests that, if the helmet was acquired in Matanda, it would have been during the meeting prior to his proclamation as sultan, since he then moved to Patikul and never returned to Matanda. Aliubdin hid in the forests of Sulu until his surrender in July 1887, while the helmet and coat of mail were already in Madrid for the exhibition.

The helmet in question is a rare wooden specimen, imitating the Spanish morions of the 16th-17th centuries. Its age and shape are quite consistent with the description in the exhibition catalogue. The helmet and coat of mail were presumably obtained by the military delegation in Matanda, but no information has been found on their final destination nor on their arrival in the collection of Diego de Saavedra.

The Philippines Exhibition, organized by Víctor Balaguer, increased the museum’s Philippine collection. Correspondence and bulletins confirm that the objects, including those from the exhibition, arrived in Vilanova before the stipulated donation to charity and within the six-month period after the exhibition closed. The possible contact between Balaguer and Pedro Ortuoste during the exhibition could explain the acquisition of the Aliubdin set. Although the Vilanova helmet resembles other Philippine helmets on display in museums, its technique and materials suggest a greater age, and no such helmet has been found in other collections or archives.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

In order to understand the dimensions of this report, it is necessary to take a brief look at the figure of Víctor Balaguer, founder of the museum. The Royal Academy of History (RAH) defines him as a politician, writer, journalist, historian and cultural patron. Although this approach is appropriate given his wide-ranging activity, it is perhaps arbitrary. Another outstanding facet of his character, his 33rd degree in Freemasonry, is not even mentioned. Also notable was his passion for the Philippine archipelago, which he himself explained in his book Islas Filipinas (Memoria), published in 1895.

In 1884—using his library and personal collections as his initial collection—he opened the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum in Vilanova i la Geltrú, an institution that offered services as a library, newspaper library, museum, and teaching centre. He also made important donations of books for the foundation of new libraries, such as the one in Sitges.

Balaguer served a third term as Minister of Overseas (from 10 October 1886 to 14 June 1888), promoting important reforms in the areas of finance, tariffs, public works, and transport and communications, as well as a progressive extension of peninsular legislation in accordance with his assimilationist positions. He also created two other library museums: the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, in Madrid—which he himself directed until his death—and the Museo Biblioteca de Filipinas, in Manila. He was as well the true architect of the organization of the Philippines Exhibition, held from 30 June to 30 October 1887.

Madrid’s Retiro Park was the venue for the exhibition. The Crystal Palace, also known at the time as the ‘Pabellón de Cristal’ (literally, Crystal Pavilion), was built for the exhibition. And although it was planned to be converted into the headquarters of the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar, this never happened.

The exhibition exhibited a group of between forty and fifty people from the Philippines along with local objects, products, and plants, recreating the ‘natural habitat’ of the indigenous Filipinos in the palace lake. This was the first human zoo in Spain in modern times. Following its success in terms of attendance, there were private companies that organized new exhibitions of people from outside Europe, both from Spanish colonies and from other countries, a practice that existed until 1942.

In the Butlletí de la BMVB of July 1887, page 5, the big news is the inauguration of the exhibition by Víctor Balaguer, under the auspices of the Queen Regent. At the end of the article, there is a separate paragraph that reads:

‘We have learned from reliable sources that many of the objects in the exhibition of Filipino products, currently open in Madrid, will be ceded by their owners to this Institution, as a token of deference and gratitude to the founder of the museum library, now Minister of Overseas, to whom the realization of such an important event is due’.

Between August 1887 and February 1888, entries of donations from the exhibition were published, but only from individual exhibitors who agreed to send their objects to Vilanova. Even so, there are several objects that do not appear in the publications of the museum’s bulletins, and which, in theory, also come from the exhibition. The reliability of the inventories of the Philippine collection is therefore questionable, insofar as they contain numerous dating, definition or cataloguing errors. Thanks to the Butlletí de la BMVB, a bulletin that was published monthly since the museum’s inauguration, where the donations and entries of objects and books were detailed with considerable accuracy, names of donors have been identified that call into question the BMVB’s inventories. Correspondence between Víctor Balaguer and the BMVB’s librarian, Joan Oliva, also provides precise information on many of these acquisitions.

With regard to the helmet under study—a piece that is part of the Bangsamoro cultures of the Muslim religion of Mindanao and Sulu—we have reviewed the different donations of Filipino objects published in the Butlletí de la BMVB, received between May 1885 and October 1901. The August 1888 publication mentions an important donation by Pedro Ortuoste y García.

Ortuoste, a translator of the languages of Mindanao and Sulu for the administration of the Government of the Philippines, was born in Manila in 1836 and was the son of a Basque official in the accountancy of the Military Treasury, assigned to the military command of Polloc (Mindanao) since at least 1852. At the age of nineteen, Ortuoste began his career as a translator, and his contemporaries noted his involvement, generosity, and bravery (which included entering combat).

From 1858 to 1879 he served as a translator, participating in military operations in Mindanao and Sulu. In 1879, he was appointed Joloan [sic] language interpreter for the Secretary of the Government General’s Office. Ortuoste was present at the signing of the Spanish sovereignty treaty in Jolo in 1878 and at the appointment of Sultan Harun in 1886.

Highly regarded in the Spanish army and administration, he was decorated on numerous occasions for his dedication beyond his salary. His knowledge of the languages of Mindanao and Sulu made him a key figure in the Spanish administration, both in war operations and in translating documents related to these islands in Manila, as well as advising Spanish commanders.

While the governors of Sulu, Mindanao and the Philippines came and went, Ortuoste was a guarantee of knowledge about the ‘Morismas’. During the 1882 crisis with Sultan Badaruddin II, General Primo de Rivera considered appointing him secretary to the Sultan of Sulu.

Ortuoste was part of the commission that attended the opening of the Philippines Exhibition in Madrid, accompanying and translating the representatives of Mindanao and Sulu who took part in it. In March 1887, Governor Terrero wrote to the Minister of Defence in Madrid, Manuel Cassola, indicating that he should take advantage of his trip to the capital to meet with Ortuoste so that he could inform him of the situation in Mindanao and Sulu, ‘which he knows better than anyone else’ (General Military Archives of Madrid [AGMM], 5460.7, 1887: 3). During his stay in Madrid, Ortuoste also met Víctor Balaguer in person, with whom he struck up a friendship, reflected in later letters from Manila.

This bond materialized in several donations to the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB) during 1888 and 1889. In his last correspondence with Balaguer, Ortuoste informed him of his intention to send the throne of the Sultan of Jolo to Vilanova, but it never arrived because he died in August 1889, while waiting for the throne pillows that he had had restored in China. Thanks to his privileged position, Ortuoste had easy access to objects not only in Mindanao and Sulu, but also in other islands in the north of the archipelago (as evidenced by the objects of Igorrote, origin present in one of his donations).

In the above-mentioned donation of August 1888, of the fifty-four objects described in the bulletin, only five actually appear in the inventories as Ortuoste’s donation. These include:

‘[…] five spears of the Moros of Mindanao; one rondache of Mindanao; six crises of Mindanao; one kampilan; two tabas, a kind of cutlass; one metal helmet; one coat of mail; one war drum, made out of metal; four guruk, a kind of metal daggers; one metal horse bit; three balasiong, a weapon of the Mindanao mountain people of the Apo volcano range; three narrower balasiong, used by the Bilime race; a salakot (or hat) of the Bayobos of Mindanao; four small baskets to carry buyo and tobacco on the marches; a guitar used by the indigenous people of the interior; two barong or bolos of Jolo […]’

Even so, this donation refers to a metal helmet, which does not coincide with the present helmet, which is made of wood, even though it has metal fittings. In the inventories of the Philippine collection, only one helmet appears, which is why we initially considered the Ortuoste donation as a possible source. It was decided to examine the Catalogue of the Philippines Exhibition in order to refine the search for possible matches. On page 305, in group 24, Diego de Saavedra appears as an exhibitor and the following entry is included:

‘Helmet and coat of mail belonging to the Sultan of Patticolo, datto Alit-mudin, candidate to the Sultanate of Jolo; the helmet, the only piece known on the island, belonged to his ancestors, two centuries after its use disappeared; it was acquired in the ranchería of Matanda, residence of the said datto’.

Almost nothing has been found on Diego de Saavedra. According to the Boletín Oficial de Filipinas of 11 June 1859, he was the owner of a merchant marine company called Hispolés, linked to the military navy, and received an honourable mention at the Madrid exhibition. However, the description of the helmet and coat of mail planking as a whole does provide important information. According to it, the hull that Saavedra presented at the exhibition belonged to Aliubdin (we have chosen to write it this way because this is how it appears in many documents of the period).

Aliubdin was one of the two pretenders to the Sulu throne after the death of Badaruddin II, who died in February 1884. He was a datu close to the Spanish regime, as he demonstrated when he presented his credentials to the Governor General of the Philippines, Primo de Rivera’s successor, Joaquín Jovellar, to whom he gave his own kris as a sign of respect. Also known to the Spanish as datu Zumbin, he ruled over Parang, Looc, Ygasang, and Patikul (AHN, 5333/1, document no. 46, 1884).

Aliubdin had been residing in the town of Matanda since January 1884, the main buildings of which (the datu‘s house and the defensive blockhouse) were newly built by a detachment of twenty-five disciplinarians provided by Colonel Parrado, ‘and which today is a marallao, marallao, as they say, which in our language means good in superlative degree, that is to say addicted to the Christian castila’ (Cirugeda, Gaceta Universal, 1884).

In Matanda, the Spanish flag was raised, and Aliubdin was presented by the press of the time, highlighting his sympathy and submission. His followers gathered in Matanda, under the shelter of a Spanish blockhouse, baptized with the name of Jovellar, with the intention of proclaiming him sultan in March 1884, after the death of Badaruddin II. A few days earlier, the late Sultan’s mother, Inchi Jamila, had sent the Spanish government a letter addressed to Alejo Álvarez, Pedro Ortuoste’s translator and companion.

In this letter, it was informed that the paduca Majazari Maulana, Sultan Muhamad, Amirol Quiram, the younger fourteen-year-old brother of the deceased, had been designated as the successor by both the datus and the cherifes. However, the council of elders (Rum-Buchara) had split into two camps, one in favour of him as the legitimate son of Diamarol, the other in favour of his uncle Aliubdin, brother of the former Sultan Diamarol.

Alerted by the military-political government of Jolo, a delegation was sent to Matanda with Captains Darnell and Zamora and the interpreter Cipriano Enrile to dissuade them from the act (Montero, II, 1888: 644). Despite attempts at negotiation, Aliubdin’s followers insisted on his proclamation. The delegation urged Aliubdin not to hold it in Matanda (possibly the fact that it was a pro-Spanish datu and housed near Spanish military infrastructure might raise suspicions among the other candidate, Amirol Quiram, and his supporters).

On the night of 13 March, Aliubdin, his family and all those gathered in Matanda moved to Patikul (‘Paticolo’ during the Spanish era), where he was proclaimed sultan, according to the act forwarded to the governor. From then on, there was the unusual circumstance of two sultans in Sulu. This went on until September 1886, when the datu of Palawan, Muhamad Harun ar-Rashid, was appointed Sultan of Sulu by the Governor General of the Philippines, Emilio Terrero, until 1893, when he abdicated. The imposition of Datu Harun as Sultan of Sulu led to a war in which Spain attempted to dominate the sultanate by force, with heavy loss of life and property for the Joloans. After Harun abdicated in 1893, Amirol Quiram was proclaimed Sultan of the archipelago.

Could it be that Aliubdin had handed over his helmet and coat of mail as a guarantee of compliance with the military delegation’s recommendations? Did the military commission force Aliubdin to leave Matanda and take his belongings? There is no confirmation of this. But if the helmet was acquired in Matanda—as described in the exhibition catalogue—it must have been during the aforementioned meeting, because after his proclamation as sultan, Aliubdin did not return to Matanda, and his residence was fixed in Patikul.

Since the capture of Maimbung, the capital of the sultanate, in April 1887, Aliubdin went into hiding with Amirol Quiram and his mother Inchi Jamila in the thick forests of the island of Jolo. In July of the same year, they finally submitted to the new sultan and emerged from hiding. At the time, both the helmet and the coat of mail were already on display in the Retiro Park in Madrid.

Another possible coincidence concerning the helmet kept in Vilanova is that it is ‘the only piece known to exist on the island, it belonged to their ancestors and has been in use for two centuries’. The helmet imitates the characteristic shape of the morions used by the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th-17th centuries, which the Muslim peoples adopted after their confrontations with the Spanish.

One of the peculiarities of the helmet is that it is mainly made of wood, whereas even at the time of the exhibition, the datus or chiefs wore helmets made of metal (brass or copper). This could support the hypothesis that it is an older helmet, which would be consistent with the description in the exhibition catalogue.

From the moment the helmet and coat of mail were presumably obtained by the military delegation in Matanda, no information has been located that would allow us to know what happened to them, or how they could have ended up in the hands of Diego de Saavedra.

It is proven that the organization of the Philippines Exhibition, directed by Víctor Balaguer himself as Minister of Overseas, was an opportunity to increase the Philippine collection, both with objects for the museum and with books for the library.

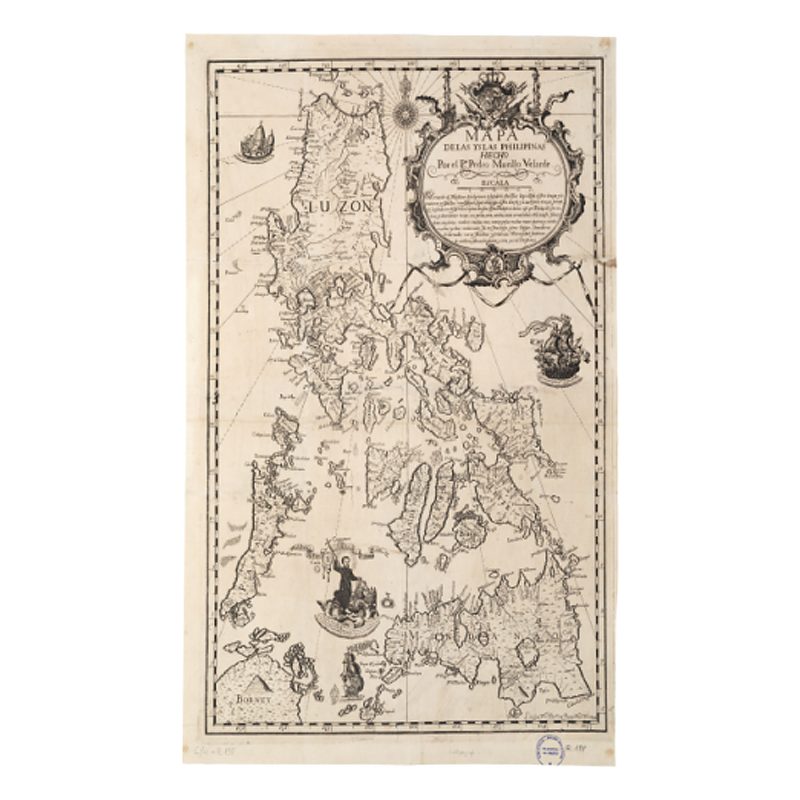

From Balaguer’s correspondence with Joan Oliva, we know that duplicates of works (where possible) were requested directly from the Philippines, as was the case with the ethnographic map of Mindanao made by the Jesuits and sent directly from the Philippines to Vilanova before the opening of the exhibition. Also, both in Balaguer’s personal correspondence and in the bulletin itself, it is explained that objects would be sent to Vilanova at the end of the exhibition.

In the rules of the organization of the exhibition, there was an article in which it was stipulated that if, after the closing of the exhibition, any objects remained unclaimed, they would be given to charity. It was also foreseen that a large part of the objects would be donated to the Museo Biblioteca de Ultramar in Madrid. It is important to note that the objects from the exhibition, and published in the bulletin, arrived before the above-mentioned deadline for donation to charity. If in this case the dating in Vilanova’s inventory is correct (as there is only one date on the inventory card), December 1887, it could be hypothesized that the piece did indeed come from Madrid.

As mentioned above, there are a number of objects from various exhibitors that arrived during this period, but without mentioning their donors. Curiously, in the six months after the exhibition closed and prior to its possible donation to charity. Perhaps the meetings with Ortuoste during the exhibition encouraged Balaguer to obtain this set of Aliubdin. Perhaps the exhibitors themselves donated these objects to Balaguer. These are only conjectures about the ultimate reason for their arrival at the BMVB.

There are some helmets, though not all that many, from Sulu and Mindanao in museums around the world, which can at least give us an idea of the type and materials they are made of. In the Peabody Museum at Harvard, there is a helmet from the Filipino Muslim cultures, dated to the 18th century (see fig. 1). In the Smithsonian in the United States, there are two more. One was collected by Robert B. Grubbs in Mindanao in 1903 (fig. 2), the other by Victor J. Evans in 1931 (fig. 3). In terms of shape, the helmet held at Vilanova is similar to the others but has much more schematic and rudimentary lines. To the left of the front, it retains a small interweaving to insert a plume, as in the helmet donated by Grubbs.

In the 19th century, the Mindanao and Sulu cultures were skilled enough in forging to make their armour and helmets from metals such as brass and bronze. The helmet in the Vilanova collection is therefore very striking, in which the seemingly rudimentary technique used to cut the helmet out of wood is offset by the decoration with metal appliqués. Both the technique and the materials and shapes achieved could confirm the age of the helmet described in the catalogue of the Madrid exhibition. So far, no such helmet has been found in the rest of the world, either in museum collections or in photographic archives on the Internet.

Estimation of provenance

13 March 1884, Matanda, Sulu Island, Sulu Archipelago, Philippine Islands

Presumably given by the datu Aliubdin to the military delegation of the politico-military government of Jolo, before moving to Patikul to be proclaimed Sultan of Sulu.

30 June 1887–30 October 1887, Philippines Exhibition, Retiro Park, Madrid, Spain.

Displayed by exhibitor Diego de Saavedra, in group 24.

December 1887–present, BMVB, Vilanova i la Geltrú, Catalonia

According to the inventory, it entered the BMVB’s Philippine collection on this date.

The helmet in question is from the Muslim Bangsamoro cultures of the Mindanao and Sulu regions of the Philippines. According to historical records and documentation on donations received by the Víctor Balaguer Library Museum (BMVB), the helmet’s provenance links the piece to relevant episodes and protagonists of Spanish colonial history in the Philippines.

The helmet may have belonged to Aliubdin, a datu and one of the two pretenders to the Sulu throne after the death of Sultan Badaruddin II in 1884. Aliubdin, also known as datu Zumbin, was a local leader loyal to the Spanish regime and ruled several areas in Sulu. It is suspected that the helmet may have been part of his personal belongings, given the detailed description found in the Catalogue of the Philippines Exhibition held in Madrid in 1887, which mentioned a ‘unique specimen helmet’ belonging to a Sulu datu.

The possible arrival of the helmet in Spain is linked to the figure of Diego de Saavedra, one of the exhibitors at the Philippines Exhibition. Saavedra presented a helmet and a coat of mail which, according to the exhibition catalogue, belonged to the Sultan of Paticolo, Datu Aliubdin. The acquisition of the helmet may have occurred during a visit of the Spanish military delegation to Matanda, Aliubdin’s place of residence, during the Sulu succession crisis of 1884.

Víctor Balaguer, founder of the BMVB and Minister of Overseas, played a crucial role in the organization of the Philippines Exhibition and in the creation of the BMVB’s collection of Filipino objects. His personal interest and contacts in the Philippines facilitated the transfer of numerous objects to the museum. Donations and correspondence documented in the institution’s bulletins show that several objects, possibly including the helmet in question, were sent from the Madrid exhibition to the BMVB in Vilanova i la Geltrú between October 1887 and February 1888.

Possible alternative classifications

Should our hypothesis be accepted as largely conclusive, the inventory information for the piece could be reformulated as follows:

Method of acquisition: Delivery or seizure to/from the Spanish Army.

Place of Acquisition: Matanda, Sulu Island, Philippines

Place of production/origin: Sulu Island

Collector: Captains Darnell and Zamora, Spanish Army

Donor or seller: Diego de Saavedra (Philippines Exhibition)

Classification group: Tausug people of Sulu Island, Philippines

Complementary sources

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 41. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 43. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1882-1883) Expediente general sobre conflictos con Joló (4.ª part). Signatura: Ultramar, 5333, exp. 1, doc. núm. 46. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1874-1889) Expediente personal de Pedro Ortuoste. Signatura: Ultramar, 52223, exp. 43. Madrid: Archivo Histórico Nacional.

(1886) Exposición general de las Islas Filipinas, 1887. Madrid: Impr. y fundición de Manuel Tello. Fons general, signatura: FP/1187. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

(1887) Concesión de recompensas a heridos y contusos en las operaciones sostenidas en Mindanao. Signatura 5460.7. Madrid: Archivo General Militar de Madrid [consulta: 19/03/2024].

Balaguer i Cirera, V. (1886-1888). Correspondencia reservada con el Gobernador general de Filipinas. Fons general, signatura 5 Ms. 113. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Boletín de la Biblioteca Museo Víctor Balaguer (1a època, 26 de juliol de 1887), (34). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

—(1a època, 26 d’agost de 1888), (47). Vilanova i la Geltrú: Imp. José A. Milá.

Cirugeda, F. (16 de gener de 1884). Carta Filipina. Gaceta Universal. Any VII, (1.854), 06/03/1884.

Crailsheim, E. (2021). Ambivalencias modernas. Guerra, comercio y «piratería» en las relaciones entre Filipinas y los sultanatos colindantes a finales del sigloXVIII. Madrid: Polifemo.

Diario de Manila. Any XXVIII, (224), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

Donoso, I. (2023). Bichara: Moro Chanceries and Jawi Legacy in the Philippines. Palgrave Macmillan. <https://www.academia.edu/98163950/Bichara_Moro_Chanceries_and_Jawi_Legacy_in_the_Philippines> [consulta: 02/11/2024].

Espina, M. A. (1888). Apuntes para hacer un libro sobre Joló: Entresacados de lo escrito por Barrantes, Bernáldez, Escosura, Francia, Giraudier, González, Parrado, Pazos y otros varios. Manila: Imprenta y Litografía de M. Pérez, hijo.

Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas Madrid (1887). Catálogo de la Exposición General de las Islas Filipinas celebrada en Madrid … el 30 de junio de 1887. Signatura: AHM/633416. Madrid: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

La Oceanía Española (4 de juliol de 1887). Any XII, (152), [consulta: 30/06/2024].

Montero y Vidal, J. (1888). Historia de la piratería Malayo-mahometana en Mindanao, Joló y Borneo. Fons general, signatura SL 5725-5726. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Oliva, J. (1887). Carta manuscrita de Joan Oliva a Víctor Balaguer. Fons epistolari de Joan Oliva, signatura Oliva/475. Vilanova i la Geltrú: Biblioteca Víctor Balaguer.

Saleeby, N. M. (1908). The History of Sulu. Filipines: Bureau of Printing.

—(2021). Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion. Txèquia: Good Press.

Sánchez Gómez, L. Á. (2003). Un imperio en la vitrina: El colonialismo español en el Pacífico y la Exposición de Filipinas de 1887. Madrid: CSIC Press.

Taviel de Andrade, E. (1887). Historia de la Exposición de las Islas Filipinas en Madrid en 1887 (2 vol.). Madrid: Imprenta de Uliano Gómez y Pérez.