Summary of results

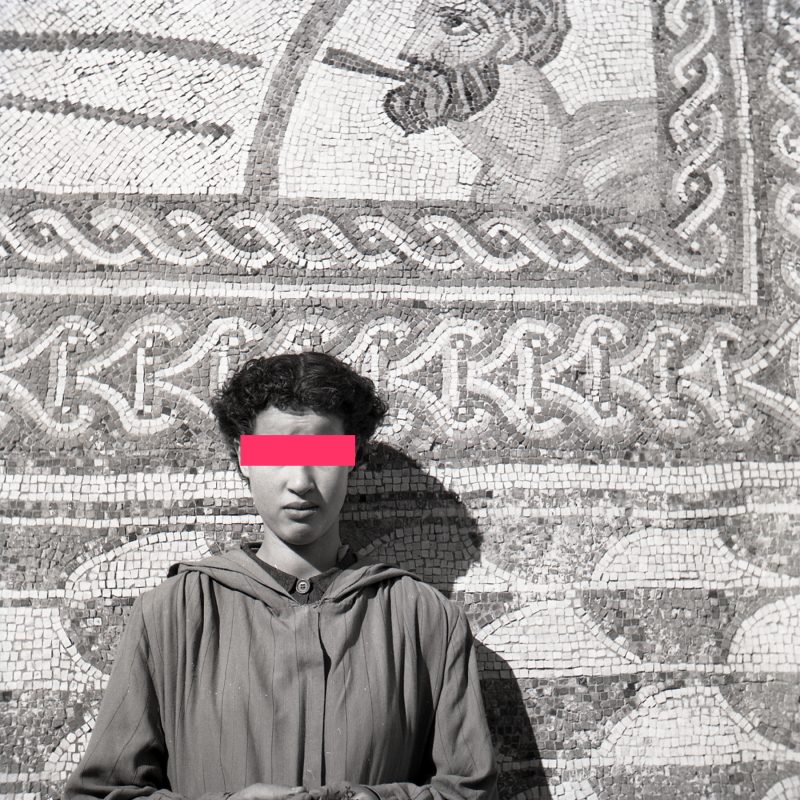

This is one of the ‘anthropological sculptures’ made by the sculptor Eudald Serra during the second expedition organized by the MEB to the northern part of the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco, in this case between 9 April and 1 May 1954. The piece, modelled in bronze, is accompanied by preliminary sketches in clay.

Despite its short duration, it was the most ambitious of the three expeditions organized by the MEB to the Protectorate. Entering through Ceuta and Tétouan, the expedition members crossed the entire Spanish-administered zone from west to east before returning by boat from Melilla to Ceuta and spending the last few days in Tétouan while Panyella prepared the abundant cargo he had to send by sea to the port of Barcelona. It was in those last days, from 28 April to 1 May, that the sculptor Eudald Serra took the opportunity to create the only nude bust of all the ‘anthropological sculptures’ in Morocco. We have evidence of the existence of this bust, first of all, in the Report on the work carried out during the second expedition to Morocco by the Ethnological and Colonial Museum of Barcelona, where Panyella states:

‘Finally, as in the first expedition, the sculptor D. Eudaldo Serra, who has participated in this one, as an attaché who has made a total of 12 heads, a nude bust and a dressed figurine, which constitute an anthropological document of the first order, precise and with a balanced artistic sense’ (MEB_L128_06_07).

In the notes that Eudald Serra himself wrote about the expedition, we can glean new information. Specifically, Serra places the making of the bust, which seems to be the result of modelling two different girls, one for the head and a second for the bust and breasts, between 28 and 29 April. Serra says:

‘28/4/54: I start the bust of the girl from the previous day. We work until 2 o’clock. I do another section from 3 to 6 […]. 29/4/54: In the morning I use another girl for the shoulders and chest. From 12 to 2 comes the other one and in the afternoon until 5 I finish the mould’ (Travel Journals, 1947–1951. Fundació Folch).

As for the identity of the models, it is difficult to reach a definitive conclusion. Serra himself gives a list of the names and tribal extraction of his models. It is quite likely that the two young women used to make piece 285-1 were among Fatima Hamu (Beni Saïd berber tribe) [sic], Nalima Mohamed Barcan (Mazuza berber tribe) [sic], Zafia Buchta Ali (Mazuza berber tribe) [sic], or Jamina Mimon Mohamed (Melilla) [sic], but to date we have no further information to clarify which of them they were. What we can say is that, given that Serra was in a great hurry to return to Barcelona on 1 May, when he arrived in Tétouan he contacted the possible models he would have met at the beginning of the second expedition, when he visited the ‘Alcazaba neighbourhood’, an area where several prostitution establishments were located, accompanied by Chaib, doorman of the Archaeological Museum and real field assistant to the expedition members on the first two expeditions (Eudald Serra, Travel Journals, 1947–1951. Folch Foundation).

However, nof these individuals match the identification provided in the catalogue Anthropological Sculptures of Eudald Serra i Güell, published by the Barcelona City Council and the Folch Foundation (1991: 37). The catalogue attributed the modeled figure to a single model named “Habiba Ben Bufrahi” [sic]. In fact, the reference to Habiba Ben Bufrahi does not appear in either the general inventory records of the MuEC or the documents related to the expeditions carried out in Morocco between 1952 and 1956. We believe this to be an erroneous attribution, likely caused by the assumption that the piece belonged to the sculptures modeled during the third expedition, in 1956. The research conducted in this case leads us to believe that Serra used two different models, whose identification is difficult or improbable, and that the modeling took place in Tetouan during the second expedition, in 1954, rather than in 1956.

The photographs taken by Serra on the occasion of the 1954 expedition have not provided sufficient clarity to determine new circumstances that would allow the models to be identified. What does emerge from August Panyella’s notes is that, in this case too, the payment to Serra’s models in Tétouan was fifty pesetas (MEB_L128_06_03).

It should be mentioned, in this case, that if the simple plastic representation of the female body contravened the system and the hegemonic gender prohibitions in Morocco, and by extension in North Africa, during the colonial period, the exhibition of the bust showing the breasts was completely inappropriate and, as a hypothesis, would only have been possible in those cases in which the woman was subjected to numerous constraints, such as those derived from the exercise of sex work or confinement in one of the colony’s various institutions of confinement.

Chronological reconstruction of provenance

While in this case we have been able to determine with some accuracy the time of modelling, it is more difficult to determine the time of the final acquisition by the museum and the total expenditure. We know, thanks to the expense reports presented by Panyella himself, that the expedition’s budget allocated 4,500 pesetas to the ‘anthropological sculptures’, and a report signed by Panyella on 5 May 1954 specifies the items to which this budget was allocated: travel expenses, subsistence allowances, and the costs of modelling and transporting the clay and plaster (MEB_L128_06_04). We do know, however, that the payment of five thousand pesetas was still pending, presumably as remuneration for the commission to Serra himself, as well as another five thousand pesetas for the casting in bronze of two of the figures, one of which, perhaps, was 285-1.

In the aforementioned Report on the work carried out during the second expedition to Morocco by the Ethnological and Colonial Museum of Barcelona, Panyella also does not clarify exactly when the final acquisition of the piece took place..

Estimation of provenance

Tétouan, Morocco, 1954

Possible alternative classifications

It seems pertinent to highlight what appears to be an attribution error in the clay sketch of piece 285-1, which is 285-1 bis. In the museum’s inventory of Eudald Serra’s ‘anthropological sculptures’, ‘Persia’ is listed as the place of provenance of the piece, which is incongruous with the identification of piece 285-1 (of which it is a sketch) as a sculpture made during the second expedition to the northern part of the Spanish Protectorate over Morocco.

Complementary sources

Archives:

Arxiu del Museu Etnològic de Barcelona

Arxiu Panyella-Amil, caixa A7 expedient 5

L128 05 02

L128 05 04

L128 06 07

L128 07 01

L128 07 02

L128 07 06

Fundació Folch de Barcelona

Eudald Serra. Cuadernos de viaje, 1947-1991

Bibliography:

Etxenagusia Atutxa, B. (2018). La prostitución en el Protectorado español en Marruecos (1912-1956) (tesi doctoral). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Goffman, E. (2007). Internados. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

Gonzalbes, E., i Parodi, M. J. (2011). Miguel Tarradell y la arqueología del Norte de Marruecos. Dins D. A., Arqueología y turismo en el Círculo del estrecho (p. 199-220). Cadis: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz.

Huera, C., i Soriano, D. (1991). Escultures antropològiques d’Eudald Serra i Güell. Barcelona: Fundació Folch i Ajuntament de Barcelona.

López Bargados, A., i Martín López, S. (2022). Entre zocos e internados. Itinerarios y procedimientos en las expediciones del Museo Etnológico y Colonial de Barcelona al Protectorado español sobre Marruecos (1952-1956). Ajuntament de Barcelona.

Madariaga, R. M. (2019). Marruecos, ese gran desconocido. Madrid: Alianza.

Marín, M. (2015). Testigos coloniales: españoles en Marruecos. Barcelona: Bellaterra.

Mateo Dieste, J. L. (2002). La paraetnografía militar colonial: poder y sistemas de clasificación social. Dins A. Ramírez i Bernabé López García (ed.), Antropología y antropólogos en Marruecos (p. 113-133). Barcelona: Bellaterra.

—(2003). La «hermandad» hispano-marroquí. Política y religión bajo el Protectorado español en Marruecos (1912-1956). Barcelona: Fundació la Caixa.

Mathieu, J., i Maury, P. H. (2013). Bousbir, la prostitution dans le Maroc colonial: ethnographie d’un quartier reserve. París: París-Méditerranée.

Mbembe, A. (2001). On the postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

—(2016). Crítica de la razón negra. Ensayo sobre el racismo contemporáneo. Barcelona: Futuro Anterior.

Rahola, F. (2007). La forme-camp. Pour une généalogie des lieux de transit et d’internement du présent. Cultures & Conflicts, 68, 31-50.

Rigoulot, P., i Kotek, J. (2000). Le siècle des camps. Détention, concentration, extermination, cent ans de mal radical. París: J.-C. Lattès.

Rivet, D. (2012). Histoire du Maroc. De Moulay Idris à Mohamed VI. París: Fayard.

Sánchez Gómez, L. A. (1992). La antropología al servicio del Estado: El instituto «Bernardino de Sahagún» del CSIC. Disparidades, 47(1), 29-44.

Smith, I. R., i Stucki, A. (2011). The colonial development of concentration camps (1868-1902). Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 39(3), 417-437.

Soriano, M. D. (2010). Historia, tradición y cultura: Las colecciones africanas del período colonial del Museu Etnològic de Barcelona. Dins Actes del 7è Congrés Ibèric de Estudis Africans (1-20). Lisboa.

Stoler, A. L., i Cooper, F. (1997). Between metropole and colony: Rethinking a research agenda. Dins F. Cooper i A. L. Stoler (ed.), Tensions of empire: Colonial cultures in a bourgeois world (p. 1-56). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stucki, A. (2018). «Frequent deaths»: The colonial development of concentration camps reconsidered, 1868-1974. Journal of Genocide Research, 20(3), 305-326. <https://doi.org/10.1080/14623528.2018.1429808>.

Taraud, C. (2003). La prostitution coloniale. Algérie, Maroc, Tunisie (1830-1962). París: Payot.

Valderrama, F. (1956). Historia de la acción cultural de España en Marruecos, 1912-1956. Tetuán: Marroquí.

Villanova, J. L. (2005). Los interventores del Protectorado español en Marruecos (1912-1956) como agentes geopolíticos. Eria, 66, 93-111.

—(2006). Los interventores. La piedra angular del Protectorado español en Marruecos. Barcelona: Bellaterra.

Zade, M. (2006). Résistance et Armée de Libération au Maroc (1947-1956). Rabat: Haut Commisariat aux Anciens Résistants et Anciens Membres de l’Armée de Libération.

![2768v2 Sr. Serra modelant cap berber al taller del fotògraf [sic]; Xauen](https://trafricants.org/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/2768v2-1-r1s3naz0e9jpfdk332eci3myow1y18s3l4ttuptphc.jpg)